| 图片: | |

|---|---|

| 名称: | |

| 描述: | |

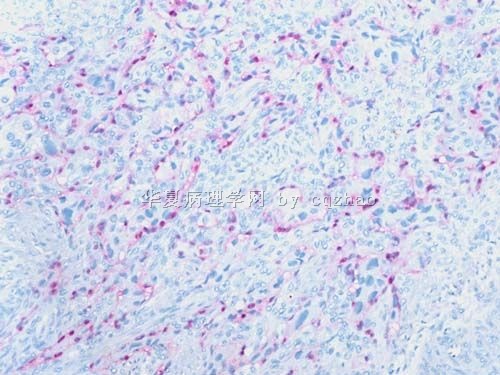

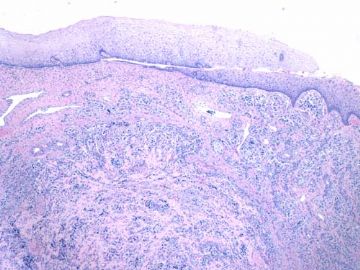

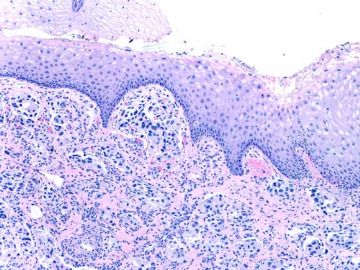

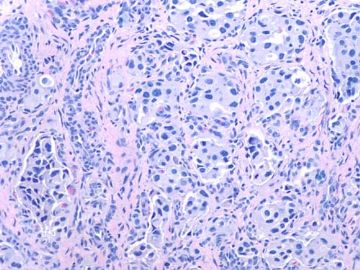

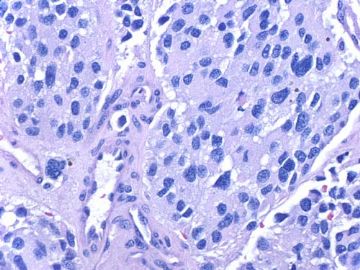

- about 40y-f cervical lesion (cqz-G12)

| 以下是引用天山望月在2010-8-15 22:33:00的发言:

神经内分泌癌是广义的名词,包括包括一大类的肿瘤,神经内分泌器官发生的肿瘤,如垂体瘤、胰岛细胞瘤、胃泌素瘤等,也包括在一些组织中的神经内分泌细胞发生的肿瘤:类癌、不典型类癌、小细胞癌、大细胞神经内分泌癌、Merkel细胞癌、Askin瘤、不能分类的神经内分泌肿瘤等。 个人觉得,类癌是神经内分泌肿瘤中的一种,具有神经内分泌的共同特点,具有器官样结构、菊形团样,细胞异型性相对小,胞浆内见神经内分泌颗粒,间质血管丰富,可有坏死, 不同的部位,不同的类型,IHC没有太大差别,HE形态不同类型及部位有不同。 Dr.zhao:不知回复如何?请指导,谢谢!

|

Good summary. Thanks.

神经内分泌癌是广义的名词 I think it is better to say that

神经内分泌瘤是广义的名词

| 以下是引用天山望月在2010-8-15 22:41:00的发言:

类癌(分化好)-不典型类癌(中分化)-小细胞癌(分化差),恶性程度逐渐增加,细胞异型性逐渐增加,对比如下:

|

-

本帖最后由 于 2010-08-16 23:19:00 编辑

学习:

以下的文献不是很新,但是对于宫颈神经内分泌肿瘤的介绍还是比较全面,文中提示宫颈神经内分泌肿瘤有角蛋白的表达,推测AE1/AE2的表达是可以的。“The Korean Journal of Pathology. 2003; 37: 373-8 Small Cell Carcinoma of the Uterine Cervix”中提示了角蛋白的明显表达。大致查找文献看到角蛋白在乳腺、肝脏、消化道、食道、胰腺、前列腺神经内分泌肿瘤中都有阳性表达的报道,未看全文,供参考。

本例病人不知是否有类癌综合征的表现,以下的文献提示宫颈类癌有时临床综合征不是很明显。

The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism Vol. 84, No. 11 4209-4213

Copyright © 1999 by The Endocrine Society

Special Articles |

Carcinoid Syndrome Caused by an Atypical Carcinoid of the Uterine Cervix

Christian A. Koch, Norio Azumi, Mary A. Furlong, Reena C. Jha, Theresa E. Kehoe, Catherine H. Trowbridge, Thomas M. O’Dorisio, George P. Chrousos and Stephen C. ClementDevelopmental Endocrinology Branch, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (C.A.K., G.P.C.), National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892; Departments of Endocrinology and Metabolism (T.E.K., C.H.T., S.C.C.), Pathology (N.A., M.A.F.), and Radiology (R.C.J.), Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC 20020; and Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism (T.M.O.), The Ohio State University Medical Center, Columbus, Ohio 43210

Address correspondence and requests for reprints to: Christian A. Koch, M.D., Developmental Endocrinology Branch, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Building 10, Room 10N262, 10 Center Drive, MSC 1862, Bethesda, Maryland 20892-1862.

| Abstract |

|---|

Neuroendocrine tumors of the cervix are rare and are often under- or misdiagnosed. Because these tumors are very aggressive, early diagnosis and subsequent treatment are warranted. We describe a 46-yr-old woman with carcinoid syndrome caused by an atypical carcinoid of the uterine cervix. At age 44, she had dysplasia on Pap smear and underwent total abdominal hysterectomy with the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma. Fourteen months postoperatively, she developed the carcinoid syndrome and was found to have numerous liver metastases. Histological and immunohistochemical investigations of biopsy specimens from the patient’s liver lesions and original cervical lesion ("adenocarcinoma") suggested that this woman had a primary atypical carcinoid of the uterine cervix with metastases to the liver. Treatment with octreotide and alkylating agents decreased the episodes of flushing and diarrhea within 8 weeks. If an adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix is diagnosed, atypical carcinoid should be in the differential diagnosis. Symptoms of the carcinoid syndrome should be pursued and, if present, a urinary 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid level should be obtained. Timely diagnosis of a neuroendocrine tumor of the cervix may improve survival.

| Introduction |

|---|

NEUROENDOCRINE tumors of the uterine cervix describe cervical neoplasms that show the histological characteristics of carcinoids, including argyrophilia and/or argentaffinnia, and immunoreactivity for chromogranin, synaptophysin, and neuron-specific enolase (1). Incidence, clinicopathological features, biological behavior, and natural history of these tumors have been difficult to estimate because various descriptive terms have been used for their broad morphologic spectrum. A recent consensus conference suggested four general categories of neuroendocrine tumors of the uterine cervix, analogous to pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors: typical (classical) and atypical carcinoid tumors, large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas, and small (oat) cell carcinomas (2).

Characteristic endocrine syndromes associated with neuroendocrine tumors of the cervix are rare (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8), with the carcinoid syndrome being extremely unusual (9, 10). Here, we describe a woman with carcinoid syndrome caused by an atypical carcinoid of the uterine cervix.

| Methods |

|---|

Tissue processing and histology

Specimens of the radical hysterectomy and liver core biopsies were fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Representative sections of the cervix and the entire liver core biopsies were routinely processed for paraffin embedding and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) for histopathological evaluation.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Paraffin-embedded sections of liver and cervix were immunohistochemically characterized with antibodies to chromogranin (dilution, 1:1500; Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN), synaptophysin (dilution 1:100; BioGenex Laboratories, Inc., San Ramon, CA), pan-keratin cocktail (prediluted; Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) (dilution 1:50; DAKO Corp., Carpinteria, CA), vimentin (prediluted; Ventana Medical Systems), and S-100 protein (dilution 1:50; Zymed Laboratories, Inc., San Francisco, CA). Bound antibodies were detected by a standard avidin-biotin complex method with a peroxidase and diaminobenzidine color development system.

Hormonal measurements

Urinary 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid (5-HIAA) was measured by high-pressure liquid chromatography (American Medical Laboratories, Chantilly, VA). RIA was used for the following hormones measured in plasma: substance P, pancreastatin (Endocrine Research Laboratories, The Ohio State University Medical Center, Columbus, OH), ACTH, gastrin, ß-human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) (American Medical Laboratories); pancreatic polypeptide (PP), glucagon, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) (Mayo Medical Laboratories, Rochester, MN), and somatostatin (Nichols Institute Diagnostics, San Juan Capistrano, CA).

| Case report |

|---|

A 46-yr-old Caucasian woman presented to us with nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and paroxysmal episodes of flushing. She was nulligravida and denied drinking alcohol or smoking. Her family history revealed diabetes mellitus but no other endocrine disorders. She was healthy until age 44, when she underwent a routine Pap smear that was abnormal (dysplasia). A subsequent biopsy of the cervix revealed adenocarcinoma in situ. The patient underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and pelvic and paraaortic lymph node dissection. Twenty-two regional lymph nodes were negative. Intraoperatively, the appendix, right pericolic gutter, right hemidiaphragm, liver, gallbladder, lesser sac, stomach, omentum, left hemidiaphragm, spleen, pancreas, kidneys, small and large bowel, and the periaortic nodal chain were macroscopically and on palpation normal. The uterus was slightly enlarged without a recognizable tumor. H and E-stained sections of the cervix showed invasive, moderately well differentiated adenocarcinoma as a well-defined nodule measuring

0.6 cm (Fig. 1A

0.6 cm (Fig. 1AFollowing radical hysterectomy, the patient initially reported occasional episodes of flushing. Fourteen months postoperatively, she developed diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, a 20-lb weight loss, and worsening paroxysmal episodes of flushing involving the face, neck, and upper trunk. She denied palpitations, dizziness, cough, shortness of breath, and taking any medications other than promethazine and Premarin. Pertinent findings on physical examination were a blood pressure of 134/78 mm Hg, a regular pulse of 91 bpm with normal heart sounds, facial erythema without Cushingoid features and with otherwise normal skin color and turgor, moist mucous membranes, no signs of pellagra, a well healed midline abdominal scar, and hepatomegaly with tenderness of the right upper and lower abdomen. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated hepatomegaly and numerous liver lesions. In addition, MRI revealed a 2.8 x 3.1-cm mass in the head of the pancreas with atrophy of the body and tail of the pancreas and dilatation of the pancreatic duct distal to the mass (Fig. 2

1-cm-sized lymph nodes were seen in the porta hepatis and peripancreatic chain, with no evidence of retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. Given these imaging findings, a primary pancreatic tumor, such as adenocarcinoma or an islet cell tumor, were considered the most likely diagnosis.

1-cm-sized lymph nodes were seen in the porta hepatis and peripancreatic chain, with no evidence of retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. Given these imaging findings, a primary pancreatic tumor, such as adenocarcinoma or an islet cell tumor, were considered the most likely diagnosis.

The pancreatic lesion was endoscopically biopsied, but results were inconclusive. CT-guided biopsies of the liver lesions revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma with a trabecular and tubular pattern with sclerosed stroma (Fig. 1C

To search for a neuroendocrine tumor, the following laboratory tests were obtained: 124 mg 24-h urinary 5-HIAA [649 µmol; normal, 0–10 mg (<52 µmol)]. Plasma measurements revealed 482 pg/mL substance P [356 pmol/L; normal, <250 pg/mL (<185 pmol/L)], 219 pg/mL pancreastatin [43 pmol/L; normal, <213 pg/mL (< 42 pmol/L)], 27 pg/mL somatostatin [16 pmol/L; normal, 10–22 pg/mL (6–13 pmol/L)], 364 pg/mL PP [87 pmol/L; normal, <270 pg/mL (< 65 pmol/L)], and 38 pg/mL glucagon [38 ng/L; normal, <61 pg/mL (< 61 ng/L)]. Results of gastrin, ACTH, VIP, insulin-like growth factor-1, and ß-HCG were normal. In serum,  -fetoprotein was normal, CA-19-9, 794 U/mL (0–36 U), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), 74.8 ng/mL (0–3 ng). Routine laboratory, including complete blood count, electrolytes, fasting blood glucose, lipase, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine, was normal. Albumin was low with 2.9 g/dL (3.5–5.5 g/dL), and liver function tests were elevated with an alkaline phosphatase of 1058 U/L (39–117 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase of 142 U/L (0–65 U/L), alanine aminotransferase of 133 U/L (0–65 U/L), and total bilirubin of 1 mg/dL (0.3–1.1 mg/dL). Given the 12-fold elevation of 5-HIAA, a carcinoid tumor was considered most likely. A subsequent 7.8 mCi Indium111-pentetreotide (10 µg) scan (Octreoscan), however, was negative.

-fetoprotein was normal, CA-19-9, 794 U/mL (0–36 U), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), 74.8 ng/mL (0–3 ng). Routine laboratory, including complete blood count, electrolytes, fasting blood glucose, lipase, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine, was normal. Albumin was low with 2.9 g/dL (3.5–5.5 g/dL), and liver function tests were elevated with an alkaline phosphatase of 1058 U/L (39–117 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase of 142 U/L (0–65 U/L), alanine aminotransferase of 133 U/L (0–65 U/L), and total bilirubin of 1 mg/dL (0.3–1.1 mg/dL). Given the 12-fold elevation of 5-HIAA, a carcinoid tumor was considered most likely. A subsequent 7.8 mCi Indium111-pentetreotide (10 µg) scan (Octreoscan), however, was negative.

Immunohistochemistry was performed on the previously obtained liver core biopsy specimens to further elucidate the primary site for the metastatic tumor. Neuroendocrine differentiation was evident with 100% of cells reacting positively for chromogranin and synaptophysin (Fig. 1D![]() ). Reactivity for keratin was also diffusely positive. Reactivity for CEA was positive in the apical pattern in 80% of the tumor cells. Vimentin and S-100 protein were negative. The liver biopsy specimens were compared with the original cervical tumor specimen, morphologically and immunohistochemically. Although nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic activity were greater, and trabecular and tubular formation were less prominent in the cervical tumor, histology was similar. Immunohistochemistry of the original tumor showed neuroendocrine differentiation, as demonstrated by chromogranin and synaptophysin positivity (Fig. 1B

). Reactivity for keratin was also diffusely positive. Reactivity for CEA was positive in the apical pattern in 80% of the tumor cells. Vimentin and S-100 protein were negative. The liver biopsy specimens were compared with the original cervical tumor specimen, morphologically and immunohistochemically. Although nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic activity were greater, and trabecular and tubular formation were less prominent in the cervical tumor, histology was similar. Immunohistochemistry of the original tumor showed neuroendocrine differentiation, as demonstrated by chromogranin and synaptophysin positivity (Fig. 1B![]() ). Because of the phenotypic and immunophenotypic similarity, both cervical and liver tumors were considered to be the same tumor (i.e., a primary atypical carcinoid tumor of the uterine cervix with metastases to the liver).

). Because of the phenotypic and immunophenotypic similarity, both cervical and liver tumors were considered to be the same tumor (i.e., a primary atypical carcinoid tumor of the uterine cervix with metastases to the liver).

Because of the extensive metastases, the patient was considered inoperable. Subsequently, the patient received weekly chemotherapy with 75 mg/sqm cisplatinum (136 mg), 2.6 g/sqm 5-fluorouracil (4.73 g), and 500 mg/sqm leucovorin (940 mg). In addition, 100 mcg octreotide sc every 8 h was initially administered and then changed to 30 mg lanreotide sc given monthly. Within 3 weeks of treatment, the patient’s liver function tests improved and almost normalized after 8 weeks of therapy. Repeated abdominal MRI, however, showed liver and pancreatic head lesions unchanged in size. The patient reported less episodes of flushing and of diarrhea.

| Discussion |

|---|

Neuroendocrine tumors of the uterine cervix are uncommon, with a range of frequencies from less than 0.5 to 5% of cancers of the cervix (8, 11, 12). The etiology of these rare neuroendocrine tumors remains unknown. Because the normal endocervix contains as many as 20% of argyrophilic cells resembling endocrine cells (12, 13), neuroendocrine tumor formation may arise from these cells. On the other hand, neuroendocrine carcinomas often show evidence of nonneuroendocrine differentiation (14), suggesting that these tumors may develop multidirectionally from primitive stem cells.

Neuroendocrine tumors of the cervix show expression of neuroendocrine markers, often argyrophilia, and characteristic morphological features defined by electron and light microscopy. Among the carcinomas of the endocervix with neuroendocrine differentiation, small cell carcinomas are well-characterized (15). Non-small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas of the uterine cervix, however, have rarely been described and are probably under- or misdiagnosed (11, 16).

Although an adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix can be associated with all four aforementioned categories of neuroendocrine tumors of the cervix, the misdiagnosis of moderately or poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma instead of carcinoid tumor can easily be made, if glandular differentiation within the neuroendocrine tumor, a separate component of nonneuroendocrine adenocarcinoma, adenocarcinoma in situ, or combinations thereof, are present. Typical cervical adenocarcinomas occasionally contain rare argyrophilic cells or focally express neuroendocrine markers (17, 18, 19). Pure cervical adenocarcinomas with neuroendocrine cells (19, 20, 21, 22), neuroendocrine cells in adenocarcinoma components (8, 23, 24, 25), and neuroendocrine carcinomas associated with adenocarcinoma (23, 24, 26, 27, 28) have been reported. Adenocarcinomas of the uterine cervix containing isolated endocrine cells (18) should not be included in any of the four categories of neuroendocrine tumors of the cervix (2).

In our patient, the diagnosis of atypical carcinoid was based on the cervix and liver tumors showing features such as increased mitotic activity, open nuclear chromatin with inconspicuous nucleoli, and strong positive reactivity for chromogranin and synaptophysin. In addition, our patient presented with the carcinoid syndrome and urinary levels of 5-HIAA 12 times above normal. The specificity of urinary 5-HIAA for carcinoid is reported to be between 88 and 100% (29, 30).

The carcinoid syndrome in neuroendocrine tumors of the cervix is very unusual. We are aware of only two other patients in whom oversecretion of 5-HIAA from a neuroendocrine cervical tumor may have caused or at least contributed to the carcinoid syndrome (9, 10). One was a 34-yr-old woman with metrorrhagia who developed facial flushing on palpation of her abdomen (9). Her 24-h urinary 5-HIAA levels were 52 mg and 198 mg, respectively. She had a 3-cm cervical tumor with lung and liver metastases, all being argentaffin. However, no other histochemical characteristics of carcinoid tumor were reported.

The second patient was a 38-yr-old woman who underwent a simple vaginal hysterectomy for menorrhagia (10). Histopathological examination showed carcinoid tumor. Abdominal CT demonstrated a low attenuation lesion of the liver. The patient developed paroxysmal facial flushing and diarrhea. Urinary 5-HIAA levels (24 h) were 145 and 237 µmol (normal, 0–58). ACTH was 262 pg/ml (<80), random serum cortisol was 1340 nmol/L (100–440), and ß-HCG was 502 IU/L (<5). Chemotherapy was initiated, but the patient died within 1 month.

The carcinoid syndrome most commonly occurs with tumors of the small intestine, appendix, and proximal colon (31). Its development is a function of tumor mass and extent of metastases, although even numerous liver metastases may not lead to the carcinoid syndrome (32). In the absence of hepatic metastases, the occurrence of the carcinoid syndrome is rare and depends on the release of mediators directly into the systemic circulation rather than the portal circulation. Potential mediators of the carcinoid syndrome are prostaglandins and vasoactive peptides such as substance P. Serotonin does not play an important role in mediating the carcinoid flush; urinary 5-HIAA levels do not correlate with the intensity of flushing (33, 34, 35).

In our patient, it remains unclear whether the initially occasional episodes of flushing that occurred after radical hysterectomy, were related to the carcinoid syndrome or merely due to estrogen/progesterone imbalance. The latter seems more likely because, at that time, our patient did not have visible liver metastases yet. However, it is possible that micrometastases in the liver or other sites with direct access to the systemic circulation could have caused the carcinoid syndrome. On the other hand, a primary carcinoid tumor other than the cervix, with direct secretion of its mediators into the systemic circulation also could have been responsible for the carcinoid syndrome. There are reports on carcinoid tumors including the appendix and ileum, with metastases to the cervix and corpus uteri (36). However, in our patient, the 1-yr latency period between radical hysterectomy and then rapid development and progression of liver metastases makes the diagnosis of a primary noncervical carcinoid tumor that initially metastasized to the cervix unlikely. Interestingly, the Indium111-pentetreotide scan (10 µg) was negative, although this scan reportedly has a sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 100% (37). In addition to the 2.8 x 3.1-cm large pancreatic mass, many of the liver metastases measured more than 2 cm on MRI and, thus, were big enough to be detected by the Octreoscan, if these lesions had possessed primarily somatostatin receptor subtypes 2, 3, and 5; however, the receptor status of the patient’s tumor remains unclear.

Although not related to clinical symptoms, the production of calcitonin (38), and the secretion of multiple hormones such as ß-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, serotonin, histamine, amylase (8), somatostatin, calcitonin, gastrin, VIP, and PP (39) have been reported in neuroendocrine tumors of the cervix. Besides high levels of 5-HIAA, CEA, and CA-19-9, our patient had mildly elevated levels of somatostatin and PP. Increased levels of CEA and CA-19–9 are commonly associated with liver and/or pancreatic disease (40).

Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the cervix are regarded as highly aggressive tumors (41) with subclinical hematogenous and lymphatic metastases frequently even in early disease. Neuroendocrine features in poorly differentiated carcinomas of the cervix indicate a poor outcome (17). Sixty-five percent of patients with cervical non-small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas die within 3 yr of diagnosis (15). Carcinoid tumor cells that stain positive for CEA, as in our patient, indicate a poor prognosis and often contain features of adenocarcinoma (31).

Treatment of neuroendocrine tumors of the cervix depends on the stage of the disease. In patients with inoperable metastatic carcinoid tumors, various chemotherapeutic regimens have been tried but none is associated with a good response. The average duration of remission remains below 1 year. Therapy with somatostatin analogs, such as octreotide and lanreotide, has resulted in reduction of the hormonal manifestations of the carcinoid syndrome (31, 42, 43), as shown in our patient.

In summary, a neuroendocrine tumor of the cervix, such as an atypical carcinoid, should be considered when an adenocarcinoma of the cervix is diagnosed. Clinical signs and symptoms of the carcinoid syndrome should be pursued. If carcinoid syndrome is suspected, a urinary 5-HIAA level should be obtained. Treatment of a cervical neuroendocrine tumor should be aggressive and directed toward the adenocarcinoma element (44).

Received June 16, 1999.

Accepted August 12, 1999.

再次学习:

像这样似癌非癌,颗粒性胞浆的首选恶黑。但是没有明显核仁。鉴别诊断(请补充,谢谢)主要是副节瘤和上皮样软组织肉瘤:

癌:鳞癌,腺癌,印戒细胞癌,Paget病,透明细胞癌,皮脂腺癌,转移癌(肾癌等)。CK排除。

神经内分泌肿瘤:Merkel细胞癌,副节瘤,类癌,不典型类癌,大细胞癌,小细胞癌。CK排除大部分。

软组织肉瘤:透明细胞肉瘤(软组织恶黑),上皮样肉瘤,腺泡状肉瘤,上皮样血管肉瘤,上皮样平滑肌肉瘤,横纹肌肉瘤,上皮样恶鞘,滑膜肉瘤

其它:ETT(CK排除),……?

华夏病理/粉蓝医疗

为基层医院病理科提供全面解决方案,

努力让人人享有便捷准确可靠的病理诊断服务。

谢谢Dr.cqzhao!

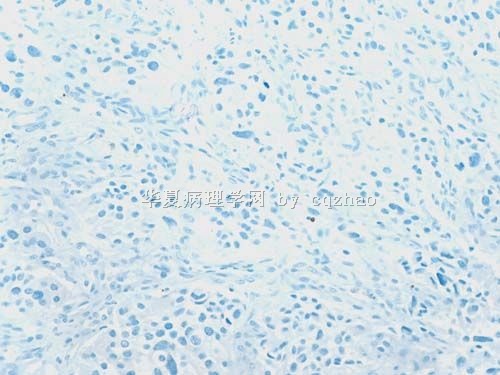

S-100显示细胞巢周围的支持细胞,确认为副节瘤。

定性:良恶性?似乎是浸润性生长的(图少判断不清)?是不是转移来的?须结合临床和病史,请Dr.cqzhao讲解。

形态特点:上皮样细胞,腺泡状结构。

鉴别诊断:见第35楼,主要是癌和ETT;神经内分泌肿瘤;上皮样软组织肉瘤。

再次感谢Dr.cqzhao提供的好病例。我对此例的学习体会:少见形态不要一下子“猜”诊断,要根据病变特点列出鉴别诊断,然后用一组免疫组化确诊或排除。

华夏病理/粉蓝医疗

为基层医院病理科提供全面解决方案,

努力让人人享有便捷准确可靠的病理诊断服务。

| 以下是引用abin在2010-8-24 7:30:00的发言:

谢谢Dr.cqzhao! S-100显示细胞巢周围的支持细胞,确认为副节瘤。 定性:良恶性?似乎是浸润性生长的(图少判断不清)?是不是转移来的?须结合临床和病史,请Dr.cqzhao讲解。 形态特点:上皮样细胞,腺泡状结构。 鉴别诊断:见第35楼,主要是癌和ETT;神经内分泌肿瘤;上皮样软组织肉瘤。 再次感谢Dr.cqzhao提供的好病例。我对此例的学习体会:少见形态不要一下子“猜”诊断,要根据病变特点列出鉴别诊断,然后用一组免疫组化确诊或排除。 |

Rare and interesting case!

Rare and interesting case!