| 图片: | |

|---|---|

| 名称: | |

| 描述: | |

- 20100727- 前列腺穿刺够癌吗?

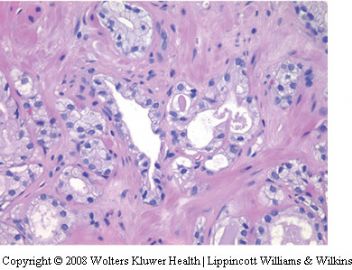

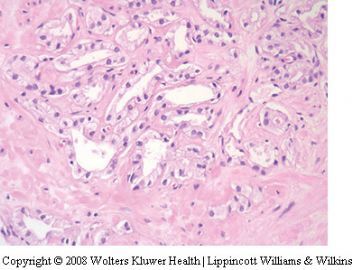

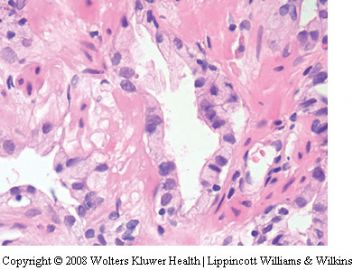

泡沫腺腺癌是前列腺腺泡性腺癌的变异型之一。活检时很少遇见。它的形态特点比较特别。主要表现在癌细胞呈丰富的泡沫样空亮的胞浆,其核浆比很低。诊断时需注意如下几点:

(一)细胞核小是造成泡沫腺腺癌诊断困难的主要因素:核相对于经典腺泡性腺癌的胞核要小得多,也不像经典型腺泡性腺癌那样核仁明显。可以说几乎见不到核仁。在前列腺活检病理诊断中,难就难在见不到胞核的异型性以致不敢诊断癌,看起来更像良性前列腺分泌性上皮的细胞核,甚至还要小。然而,泡沫腺腺癌的细胞核是深染的,多少有些大小不是很一致。

(二)腺体结构及细胞形态:由泡沫样空亮胞浆的细胞构成,胞浆丰富,核浆比较小。细胞呈矮立方或柱状(核较靠近基底),多呈单层排列,由于胞浆泡沫样且透亮或极其淡染,故显示出细胞界限清晰(细胞膜所在位置呈线状界限)。腺腔内可含红染的分泌物。没有基底细胞。但腺体构筑或浸润与经典腺泡性腺癌一致。

(三)泡沫腺腺癌不是低级别腺癌,绝大多数判为中等级别,千万不要因为泡沫腺的良性结构被误认为是低级别腺癌。

(四)标记物标记与经典性腺泡性腺癌一样。

学习随记,仅供参考。

- 王军臣

| 以下是引用doudou20080626在2010-8-23 17:30:00的发言: 学习了,前段时间遇到一例,本人考虑为高分化癌,科主任直接给我否定了。其实它的PSA也是25,P63部分腺体不表达。迷惑的是我们的P504S阴性。 |

P504S这个抗体做出来有时是会使人困惑,这其中有技术方面的原因,也有抗体供应方面的问题。

技术上的问题主要可能有固定是否及时的因素,因为P504s是一种参与脂肪酸支链及其之间产物代谢的酶,如果固定不及时或固定不良,容易导致该酶降解。技术上的因素还有抗原修复的步骤没掌握好火候,这个平常要拿阳性对照片去试,看什么样的修复温度和修复时间比较合适。还有一些IHC操作细节问题。

抗体供应上的问题主要是这个抗体使用的相对较少,所以在购买前供应商那里可能储藏的时间较长,其效价降低,特别是即用型抗体,买来后很少用而久存,也会降低效价。这时,解决的办法就是在即用型抗体中,加几滴未稀释的原始一抗,以提供有效抗体效价,说不定使用起来效果会好些。

仅供参考。

- 王军臣

-

lantian0508 离线

- 帖子:1250

- 粉蓝豆:42

- 经验:1495

- 注册时间:2007-08-01

- 加关注 | 发消息

-

本帖最后由 于 2010-08-01 01:44:00 编辑

Benign mimickers of prostatic adenocarcinoma

John R Srigley

Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

The diagnosis of prostatic adenocarcinoma, especially when present in small amounts, is often challenging.Before making a diagnosis of carcinoma, it is prudent for the pathologist to consider the various benign patterns and processes that can simulate prostatic adenocarcinoma. A useful method of classifying benign mimickers is in relationship to the major growth patterns depicted in the classical Gleason diagram. The four major patterns are small gland, large gland, fused gland and solid. Most mimickers fit within the small gland category and the most common ones giving rise to false-positive cancer diagnosis are atrophy, post-atrophic hyperplasia, atypical adenomatous hyperplasia and seminal vesicle-type tissue. A number of other

histoanatomic structures such as Cowper’s gland, verumontanum mucosal glands, mesonephric glands and paraganglionic tissue may be confused with adenocarcinoma. Additionally, metaplastic and hyperplastic processes within the prostate may be confused with adenocarcinoma. Furthermore, inflammatory processes including granulomatous prostatitis, xanthogranulomatous prostatitis and malakoplakia may simulate highgrade adenocarcinoma. Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (adenosis), a putative precursor of transition zone adenocarcinoma, has overlapping features with low-grade adenocarcinoma and may cause problems in differential diagnosis, especially in the needle biopsy setting. The pathologist’s awareness of the vast array of benign mimickers is important in the systematic approach to the diagnosis of prostatic adenocarcinoma. Knowledge of these patterns on routine microscopy coupled with the prudent use of immunohistochemistry will lead to a correct diagnosis and avert a false-positive cancer interpretation.

Modern Pathology (2004) 17, 328–348, advance online publication, 13 February 2004; doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800055

Keywords: prostate gland; adenocarcinoma; mimickers; benign

Prostatic adenocarcinoma is characterized by diverse architectural patterns and as such can be confused with other histological patterns and processes. Histoanatomic structures such as seminal vesicle, inflammatory and reactive conditions and

pathophysiological processes including atrophy,hyperplasia and metaplasia have protean patterns which may simulate adenocarcinoma. Most of these lesions are readily recognized and easily separated from malignancy but they may present problems, especially when dealing with limited sampling in thin core needle biopsies. False-positive cancer diagnosis, albeit uncommon, may be rendered in

some cases leading to serious clinical, psychological and medicolegal consequences. Prostatic biopsy pathology has been identified as a problem area which may lead to litigation.1–3 In my own experience,the most likely patterns giving rise to falsepositive malignant cells are atrophy, post-atrophic hyperplasia, atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (adenosis) and seminal vesicle.

In this paper, the differential diagnosis of prostatic adenocarcinoma will be discussed with emphasis on benign mimickers as outlined in Table 1.Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and other carcinomas may be confused with prostatic adenocarcinoma but these topics will not be addressed. The mimickers of other rare prostatic malignancies such as sarcoma will not be covered. The differential

diagnosis of adenocarcinoma has been detailed in several recent reviews and monographs.4–10

A pattern-based approach to differential diagnosis

The utility of the now famous Gleason diagram extends beyond its role as a grading tool.11,12 It is useful in a discussion of the protean architectural patterns that are important in diagnosing prostatic adenocarcinoma. Additionally, it provides a conceptual framework for discussing differential diagnosis.

In the Gleason diagram, there are nine patterns which can be lumped into four major

architectural categories for discussion of differential diagnosis (see Figure 1 and Table 2).The predominant pattern of adenocarcinoma is the small glandular one. This corresponds to Gleason patterns 1, 2, 3A, 3B and consists of separate acini which may be tiny, small or medium in size. Most benign mimickers enter the differential

diagnosis of small acinar adenocarcinoma.The second major pattern is the large glandular one. Medium to large simple acini and/or papillary and cribriform structures are seen. Central (comedo)necrosis involving round duct-like structures may also be identified. The large gland architecture includes Gleason patterns 3A, 3C and 5A.The third major growth pattern of adenocarcinoma is fused glandular which comprises Gleason patterns 4A and 4B. The infiltrating coalesced glands may be either amphophilic (Gleason 4A) or clear (so-called hypernephroid; Gleason 4B). A few

structures and benign processes simulate this fused gland pattern.The final major pattern of adenocarcinoma is the solid one which consists of sheets, cords and single

infiltrating cells and corresponds to a pattern 5B in the Gleason chart. Certain inflammatory lesions may be confused with solid adenocarcinoma.

A benign mimicker may in some situations simulate more than one major pattern of adenocarcinoma. For instance, reactive atypia involving small acini can be mistaken for small acinar carcinoma. However, if the atypia affects medium to large glands, then the differential diagnosis is with the large gland pattern of carcinoma.

The benign mimickers and the corresponding patterns of adenocarcinoma that may be simulated are shown in Table 3. The discussion of these entities will follow this pattern-based approach.

Small Gland Pattern

Seminal vesicle

Seminal vesicle tissue may be present in transurethral resectates or in needle biopsies, usually unexpectedly, but sometimes as a result of specific sampling.13,14 The seminal vesicle is characterized by a central lumen with branching glands surrounded by smooth muscle. Commonly, the end Table 1 Classification of benign mimickers of adenocarcinoma Histoanatomic structures Reactive atypia Seminal vesicle/ejaculatory branching is complex with numerous small glands,resulting in the so-called adenotic pattern of seminal vesicle (Figure 2). This latter pattern can present problems, especially when the overall gland structure and central lumen are not recognized. Tangential sampling of adenotic areas in a needle biopsy may produce a small gland pattern causing confusion with small acinar carcinoma.15 Helpful features to distinguish adenotic seminal vesicle include the presence of nuclear hyperchromasia and pleomorphism which at times is striking.13,16 The degree

of atypia is thought to increase with advancing age.13 Atypical cells are found centrally within the acini and they are often more atypical than the nuclei of small acinar carcinoma (Figure 2). Mitoses are not identified. Small nuclear pseudoinclusions are commonly seen. In the cytoplasm, golden-brown lipofuscin pigment is usually identified, although the amount varies from case to case. When prominent,the diagnosis of seminal vesicle epithelium is easily supported.

It must be remembered however that lipofuscin pigment may be present in normal, hyperplastic,preneoplastic (PIN) and carcinomatous glands.17–19

The presence of lipofuscin pigment in small acinar carcinoma however is rare. When the epithelial atypia and pigmentation are not prominent, a significant diagnostic challenge may result. In problematic cases, negative immunohistochemistry

for prostatic-specific antigen (PSA) and prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP) helpful. Additionally, the 34bE12 stain shows basal cells in seminal vesicular glands which of course are absent in small acinar carcinoma. Ejaculatory duct epithelium has a similar morphology to that of the seminal vesicle. Ejaculatory ducts however are surrounded by a band of loose fibrovascular connective tissue and lack the wellformed

muscular wall of seminal vesicle. This

distinction is of practical importance since the

presence of carcinoma in ejaculatory duct tissue

does not indicate extraprostatic disease whereas

carcinomatous involvement of seminal vesicle proper

indicates high stage disease (at least stage pT3b)

and has adverse prognostic significance.

Cowper’s gland

Cowper’s glands, also referred to as the bulbourethral

glands are paired periurethral structures

located near the prostatic apex.20,21 They are rarely

sampled in prostatic specimens. Cowper’s glands

have a lobular configuration with a central duct

surrounded by tightly packed round acini composed

of cells with abundant mucinous cytoplasm (Figure

3). The nuclei are basally located and uniform.

Sometimes, skeletal muscle, typical of the apical

region, is present in the periglandular stroma.

Cowper’s glands are rarely confused with small

acinar carcinoma. The duct-acinar architecture,

cytoplasmic mucin and lack of cellular atypia

distinguish Cowper’s glands from adenocarcinoma.

In difficult cases, special stains for mucin (mucicarmine,

PAS-D) may be employed. Cowper’s glands

show variable staining results for PSA and are

negative for PAP.20,21 The ductal cells exhibit high

molecular weight keratin (34bE12) staining and in

some cases attenuated cells around the periphery of

the acini are also positive.20 The latter cells may also

exhibit smooth muscle actin positivity.20,21 Another

differential diagnosis of Cowper’s glands is mucinous

metaplasia of prostatic acini which is usually

seen in association with atrophy.22

Atrophy

Atrophy of prostatic glands is a common process

typically but not exclusively found in older patients.

Atrophy may be seen in the young adult prostate

and is commonly admixed with areas of nodular

prostatic hyperplasia.23 While common in the

peripheral zone, atrophy may also be seen in the

central and transition zones. Glandular atrophy is

commonly associated with chronic prostatitis which

may have an active component characterized by

intraglandular neutrophils. Some recent evidence

suggests that prostatic atrophy may be a manifestation

of chronic ischemic disease, although many

examples of atrophy are still considered idiopathic

in nature.24 Atrophy can also be the result of

treatment with radiation and antiandrogens25–30

(Figure 4). Treatment-associated atrophy is frequently

extensive and severe and in the case of

radiation may be associated with epithelial atypia.

Four main patterns of atrophy are recognized—

lobular (simple), sclerotic, cystic and linear or

streaming (Figure 5). Combined patterns are common.

Lobular (simple) atrophy is characterized by

small glands arranged in circumscribed (lobular)

nests. The orderly architecture is best appreciated

on low power. In sclerotic atrophy, the small glands

are distorted by dense collagenized stroma which

results in sharply angulated and irregular shapes.

The stroma often has an elastotic appearance similar

to that seen in some breast conditions. At low

power, the lobular architecture is usually evident

and sometimes a central dilated duct is appreciated.

The almost desmoplastic appearance of the stroma

in sclerotic atrophy contrasts with low grade, small

acinar carcinoma which incites little or no stromal

response. In cystic atrophy, varying degrees of acinar

dilatation are seen and usually other areas of more

typical simple atrophy are found nearby. Occasionally,

atrophy may have a linear, streaming pattern in

which small dark acini are lined up in a row,

seemingly permeating through stroma. This latter

pattern is particularly prone to be overinterpreted as

carcinoma.

Regardless of the architectural subtype of atrophy,

the cytological features are similar. The cells are

small, shrunken and dark. They have high nuclear to

cytoplasmic ratios but the nuclei are uniform and

lack nuclear membrane irregularity and chromatin

abnormalities. Occasionally, small chromocenters

are seen but prominent nucleoli are absent. Double

layering of cells is often seen but in some instances

it may be difficult to appreciate because of the

marked secretory cell atrophy (Figure 6). In such

cases, stains for high molecular weight keratin

(34bE12) may be employed to highlight the basal

cell compartment.31

The important features in separating atrophy from

small acinar carcinoma are the low power maintenance

of lobular architecture at least in part,

uniform cytology and absence of prominent nucleoli.

In some cases, especially when the atrophy is

along the edge of a biopsy or when distortion or

secondary inflammation is present, diagnosis may

be difficult and special stains for high molecular

weight keratin should be employed.

In a series of secondary reviews of prostatic

pathology prior to definitive treatment, atrophy

was a lesion in needle biopsies sometimes

overinterpreted as adenocarcinoma.32 It should

be emphasized that carcinoma may have an

atrophic appearance and as such may be underinterpreted

as atrophy. Atrophic adenocarcinomas

are composed of small dark acini usually with

an irregular permeative pattern of growth. On

close inspection, there is nuclear atypia and nucleoli

are usually recognized at least focally. In some

instances, 34bE12 staining may be required

to distinguish the atrophic adenocarcinoma from

atrophy.33,34

Atrophy associated with inflammation, especially

active inflammation, may be particularly challenging

and one should be cautious in diagnosing

carcinoma in inflamed small gland foci. Additionally,

in the setting of radiation, atrophy may be

severe and may be associated with stromal

fibrosis. This may result in architectural distortion

which when coupled with cytological atypia

typical of radiation effects can cause considerable

diagnostic confusion. In such cases, high molecular

weight keratin stains (34bE12) are useful to

separate non-neoplastic atrophic glands from

residual carcinoma.

Post-atrophic hyperplasia

Post-atrophic hyperplasia, also referred to as partial

atrophy or hyperplastic atrophy is an uncommon

histological process found in about 2–3% of prostatic

needle biopsy cases.35–38 It is usually found in

the peripheral zone. In most cases, it is difficult to

know if post-atrophic hyperplasia represents a

normal or hyperplastic focus undergoing atrophy

(partial atrophy) or secondary hyperplasia occurring

in atrophic areas. Studies with proliferation markers

however show increased proliferation in areas of

post-atrophic hyperplasia, thus supporting the latter

hypothesis.39,40

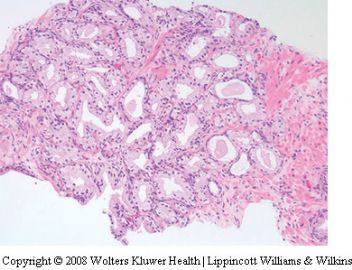

Post-atrophic hyperplasia consists of a combination

of atrophic acini and ones that contain more

abundant clear or amphophilic cytoplasm and

appear hyperplastic (Figure 7). The lobular arrangement

is usually maintained and there is often

apparent budding of ‘neoacini’ lined by cuboidal

cells with clear cytoplasm. A mixture of cells with

atrophic and nonatrophic cytoplasm leads to a

variety of irregular glandular shapes including

stellate ones. Some nuclear enlargement may be

seen and rarely, enlarged nucleoli are identified. The

busy architecture of post-atrophic hyperplasia may

cause diagnostic confusion with adenocarcinoma,

however there is generally a maintenance of some

degree of lobular architecture and basal cells are

usually recognized, even at the H&E level. Caution

should be exercised whenever there is an admixture

of atrophic and nonatrophic acini, especially when a

lobular pattern is not readily recognized. Prominent

nucleoli in a significant number of cells are not

typically found in post-atrophic hyperplasia. The

prudent use of high molecular weight keratin

(34bE12) immunostains is important in difficult

cases. There is a discontinuous layer of basal cells

in post-atrophic hyperplasia whereas in small acinar

carcinoma, the basal cell layer is completely absent.

In rare instances, luminal crystalloids and even

small amounts of basophilic luminal mucus may be

present in post-atrophic hyperplasia.

The early ideas of Franks and Laivag that atrophy

and post-atrophic hyperplasia are involved in the

pathogenesis of prostatic cancer were largely ignored

until recently.35,39 The common topographic

association of prostatic carcinoma, atrophy and

chronic inflammation is well known but most

investigations had been focused on other putative

precursors such as prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia

(PIN) and atypical adenomatous hyperplasia

(adenosis). De Marzo and co-workers have recently

identified a lesion which they refer to as proliferative

inflammatory atrophy which may represent a

precursor of adenocarcinoma.40–42 This lesion is

morphologically represented by areas of simple

atrophy and/or post-atrophic hyperplasia in which

there is superimposed chronic inflammation. Using

immunohistochemistry, the above authors have

identified areas of high cell proliferation in which

there is increased staining of P-glutathione stransferase

(GSTP1) and bcl-2 along with decreased

staining of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor

p27. The findings suggest that the cells of the

secretory compartment in proliferative inflammatory

atrophy have an immature secretory phenotype

similar to that seen in cells of high-grade PIN and

carcinoma. The authors have identified areas of

atrophy merging into high-grade PIN within the

same glands. They suggest that proliferative inflammatory

atrophy may give rise to carcinoma, either

directly or through high-grade PIN as an intermediary

step. Clearly, further investigations are required

to evaluate this hypothesis. It should be stressed

however that proliferative inflammatory atrophy is a

lesion which is not defined solely on the basis of the

H&E morphology but requires immunohistochemical

markers of proliferation and differentiation for

identification.

Reactive atypia

Epithelial atypia may be seen in association with

acute or chronic prostatitis and may sometimes be

present in association with prostatic ischemia

(infarction). Reactive atypia can be confused with

adenocarcinoma43–45 (Figure 8). The glands in most

cases of reactive atypia are atrophic and there may

be some associated basal cell or transitional cell

hyperplasia. In some cases, especially in ischemia,

the epithelium may have a squamoid appearance

and frank squamous or transitional metaplasia may

be present (Figure 9). Mild to moderate nuclear

enlargement is seen and sometimes nucleoli are

prominent. The nucleolar enlargement may actually

exceed that of adenocarcinoma.

The low-power architecture, presence of basal

cells and degree of cytological atypia usually allow

separation of reactive lesions from adenocarcinoma.

However, adenocarcinoma may be present in areas

of prostatitis and ischemia and as such diagnostic

caution should prevail.

A special situation of reactive atypia is radiation

effects.26,27 The degree of cytological atypia in

irradiated prostates may be severe with enlarged,

hyperchromatic nuclei and prominent nucleoli. The

low-power architectural arrangement of the atypical

glands is helpful in separating radiation atypia from

residual adenocarcinoma. Other radiation-associated

changes include prominent atrophy, transitional

cell and squamous metaplasia, stromal

fibrosis, edema and changes within prostatic arteries.

In difficult cases, immunohistochemistry for

high molecular weight keratin (34bE12) is invaluable

in resolving the differential diagnosis.

Mucinous metaplasia

Mucin-producing cells are sometimes identified

within prostatic glands, usually atrophic ones.22 As

such, this process may enter the differential diagnosis

of small acinar carcinoma. The lobular pattern

of the associated atrophy usually points to the

benign nature of this lesion (Figure 10). Individual

mucous cells have a vacuolated appearance on H&E

and highlighted by mucicarmine and PAS stains.

When there is florid mucinous metaplasia, especially

in an apical location, confusion with Cowper’s

(bulbourethral) glands may occur.20,21

Nephrogenic metaplasia (adenoma)

Nephrogenic metaplasia (adenoma) is uncommonly

encountered in the prostatic urethra, and subjacent

prostatic tissue.46–49 It may be present as an

exophytic (papillary) lesion or as a flat or nodular

abnormality. In most instances, there has been a

previous history of trauma, instrumentation or

transurethral resection. Problems can arise when a

prior transurethral resection has revealed adenocarcinoma.

Nephrogenic metaplasia displays exophytic papillary

and tubulocystic elements. The latter may

have a pseudoinvasive growth pattern (Figure 11).

The acini of nephrogenic metaplasia are usually

small and the cells have scant cytoplasm. Sometimes

they may have more abundant clear cytoplasm.

At least focally, the tubules may display

cystic change and sometimes hobnail cells are

identified. Commonly, the adjacent stroma is both

edematous and inflamed.

The small size of the acini, cystic dilatation and

inflamed stroma separate nephrogenic metaplasia

from small acinar carcinoma. High molecular weight

keratin (34bE12) is positive in some but not all cases

of nephrogenic metaplasia.49 When positive, it is a

helpful adjunctive test. The PSA and PAP stains are

usually negative but there may be focal positivity of

tubular cells and/or secretions.49

A recent study suggests that nephrogenic metaplasia

(adenoma) is neither metaplastic nor neoplastic

in nature.50 Molecular studies in the setting of

transplantation suggest that this lesion is truly

nephrogenic in origin and results from the implantation

of renal tubular cells at sites of prior

urothelial injury with subsequent proliferation of

epithelial elements.

Basal cell hyperplasia

Basal cell hyperplasia is typically seen as part of the

spectrum of nodular hyperplasia usually in samples

from the transition zone.51–54 Recently, it has been

recognized that basal cell hyperplasia may also

affect the peripheral zone.55 It is usually identified

in transurethral resection specimens but may be

encountered in needle biopsies (Figure 12). Basal

cell hyperplasia may also occur in association with

atrophy, usually in the setting of antiandrogen

therapy.28–30 Basal cell hyperplasia may be confused

with adenocarcinoma.

Basal cell hyperplasia is usually characterized by

nodular expansion of uniform round glands associated

with a cellular stroma. It may be complete or

incomplete.15 There is a lack of secretory (luminal)

cell differentiation in the complete form in which

solid nests of dark-blue cells are present. In the

incomplete form, there are residual small lumina

lined by secretory cells with clear cytoplasm and

these are surrounded by multiple layers of basal

cells. In each type, the basal cells are dark and have

scant cytoplasm and display round, oval or somewhat

spindled hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 12).

Nucleoli are usually indistinct but in some

examples of the so-called atypical basal cell hyperplasia,

nucleoli may be more prominent.53,56 Microcalcifications

are present in up to half of the cases of

basal cell hyperplasia. The adjacent stroma is often

hypercellular and consists of proliferating fibroblasts

and smooth muscle cells similar to those seen

in usual nodular hyperplasia.

Basal cell hyperplasia is readily separated from

adenocarcinoma in most cases, especially in transurethral

resectate and prostatectomy specimens.

The nodular arrangement, association with ordinary

nodular hyperplasia, cellular uniformity and lack of

prominent nucleoli serve to separate this condition

from cancer. It may be more difficult however in

small biopsies in which part of a focus of basal cell

hyperplasia is only partially represented. In such

cases, the distinction relies on the identification of

uniform cytological and nuclear features and in

some instances may require immunohistochemical

staining for high molecular weight keratin

(34bE12).52

Benign nodular hyperplasia, small gland pattern

Benign nodular hyperplasia of prostate can have a

variety of morphologies including predominantly

stromal, mixed glandular and stromal, and predominantly

glandular growth patterns.9,15 The glandular

elements usually consist of medium to large

acini, often showing luminal papillae. Occasionally,

areas of nodular hyperplasia are composed of

mainly small to medium sized, closely packed acini

with rounded lumens.

Usually basal cells are readily identified and

small amounts of intervening cellular stroma are

seen. The nodular circumscription, uniform architecture,

presence of basal cells and intervening

stroma serve to separate this proliferative pattern

from low-grade (Gleason patterns 1, 2) adenocarcinoma

(Figure 13).

It is probably more common for adenocarcinoma

to mimic benign nodular hyperplasia than the

converse. The pseudohyperplastic pattern of adenocarcinoma

is composed of medium to large acini

that may have a somewhat nodular appearance on

low power.57,58 This form of carcinoma can be

deceptively bland and may only be suspected when

there is a subtle disruption of the normal gland/

stroma relationship on low power. This observation

can be quite difficult in thin core biopsies. On

higher power, there is an absence of basal cells and

the typical nuclear features of adenocarcinoma are

present. The cells comprising this lesion are usually

high cuboidal to columnar cells with abundant

apical, often clear cytoplasm. These cells resemble

the appearance of the secretory cell compartment in

benign nodular hyperplasia aside from their nuclear

features. The 34bE12 stain is invaluable in confirming

a diagnosis of pseudohyperplastic adenocarcinoma.

Sclerosing adenosis

The term sclerosing adenosis of the prostate was

first used by Young and Clement in 1987 to describe

an unusual prostatic proliferative lesion which

resembled to some extent sclerosing adenosis of

breast.59 There had been an earlier report in which

the term adenomatoid tumor was used.60 Sclerosing

adenosis is an uncommon lesion largely restricted to

the transition zone and is generally an incidental

finding in transurethral resectates or radical prostatectomy

specimens. It is rarely seen in needle

biopsies. A few series of sclerosing adenosis cases

have been reported.61–63

Sclerosing adenosis is characterized by a more or

less circumscribed proliferation of variably sized,

often small glands embedded in a cellular and often

edematous stroma (Figure 14). Sometimes the lightly

basophilic stroma is recognized on low power. Tiny

microacini, cords, solid clusters and single cells are

seen. A double layer is present but may be difficult

to appreciate with the H&E stain. The lining cells

often have open nuclear chromatin with inconspicuous

nucleoli although prominent nucleoli may be

focally present. Glandular lumens may contain

crystalloids or occasionally acid mucin. A characteristic

feature is the present of a thick eosinophilic

basement membrane around at least some glands.

Sclerosing adenosis is unique in that the basal

cells in this condition undergo myoepithelial metaplasia

and show coexpression of both high molecular

weight cytokeratin and muscle-specific actin

(HHF-35)63 (Figure 14). S100 protein is also positive

in these cells. The myoepithelial differentiation has

been confirmed by electron microscopic studies.

The key features distinguishing sclerosing adenosis

from adenocarcinoma include the variation in

gland size and shape, thickened basement membranes

and cellular stroma. Immunohistochemistry

for high molecular weight keratin (34bE12) and actin

can be used in problematic cases.

Verumontanum mucosal gland hyperplasia

Verumontanum mucosal gland hyperplasia is identified

as an incidental finding in radical prostatectomy

specimens.64 In all, 14% of 30 radical

prostatectomy specimens in one series contained

one or more foci of hyperplastic verumontanum

mucosal glands. This process is rarely encountered

in needle biopsy specimens.65 It is characterized by

relatively uniform, closely packed, round glands

containing numerous corpora amylacea which may

have a red or orange-brown coloration (Figure 15).

Basal cells are usually identified and there is a lack

of nuclear features of malignancy. In particular,

prominent nucleoli are not seen. Lipofuscin pigment

may be present within the cytoplasm of

glandular cells. Prostatic urethral tissue is often seen

nearby and islands of transitional cell epithelium

may be present in or adjacent to the proliferating

verumontanum glands. The suburethral location,

acinar and cellular uniformity, basal cells and

prominent corpora amylacea allow separation of

this entity from low-grade adenocarcinoma. Recently

verumontanum mucosal gland hyperplasia

has been associated with atypical adenomatous

hyperplasia in a radical prostatectomy series.66

Hyperplasia of mesonephric glands

Mesonephric gland remnants are rarely identified

in prostatic specimens.67–71 In a series of close to

700 transurethral resectates, 0.6% contained mesonephric

remnants.70 Mesonephric gland remnants

occasionally undergo hyperplasia and may be

confused with adenocarcinoma. Gikas et al identified

two cases in transurethral resection specimens

that were interpreted as adenocarcinoma which

in one instance led to an unnecessary radical

prostatectomy.67 The hyperplastic mesonephric

glands are typically small and may have an

infiltrative appearance (Figure 16). Sometimes

tubular dilatation, epithelial tufting and micropapillary

formations are seen. They may demonstrate

perineural spread and extraprostatic extension.

Mesonephric glands are lined by a single layer

of cuboidal cells. Typically, the small glands contain

a dense eosinophilic luminal substance which

contrasts with the loose granular eosinophilic

material typical of small acinar carcinoma (Figure

16). Immunohistochemistry may be helpful in

difficult cases. The glands of mesonephric hyperplasia

stain negatively for PSA and PAP and often

positively for high molecular weight cytokeratin

(34bE12) in contrast to adenocarcinoma which lacks

34bE12 basal cells.

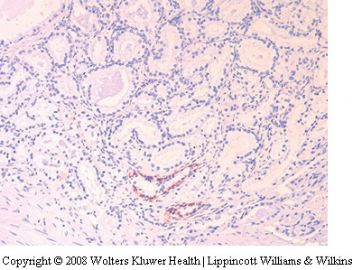

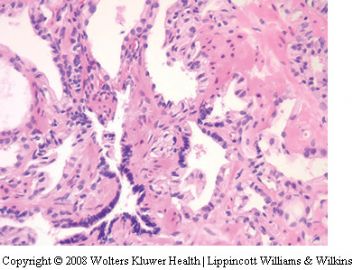

Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (adenosis)

Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) is a

proliferative lesion characterized by crowded small

acini, usually forming well circumscribed nodules

which often simulate the small gland pattern of

carcinoma.72–78 While many authors use the term

Figure 15 Verumontanum mucosal gland hyperplasia. (a) Lowpower

appearance in needle biopsy. (b) High-power appearance

showing tightly packed small acini with prominent corpora

amylacea.

‘atypical adenomatous hyperplasia’ others prefer

the rubric ‘adenosis’.79–83 AAH is a well-defined

entity but the term ‘adenosis’ has been used more

loosely, even to the extent that some examples of

adenosis have been interpreted by experts as

adenocarcinoma.84

AAH has been identified in 1.5–19.6% of transurethral

resectates and in up to 33% of radical

prostatectomy specimens.9 It is uncommon in

needle biopsy specimens but occasionally occurs.82

Most evidence associating AAH with carcinoma is

circumstantial.9,75,78 AAH has a predilection for the

transition zone and morphologically simulates low

grade (Gleason 1, 2) carcinoma. Examples of small

acinar carcinoma arising in relationship to AAH

have been reported. Additionally, the age of patients

with AAH is usually 5–10 years, less than those

with carcinoma.

The basal cell-specific keratin stain shows a

discontinuous pattern which is intermediate between

the continuous pattern of normal prostate and

the absence of basal cells in carcinoma.8,74,85 Studies

with tridiated thymidine, immunohistochemistry

for proliferation markers (Ki67/M1B-1) and silver

staining of nucleolar-organizer regions suggest that

AAH has a proliferation rate between benign

prostate hyperplasia and low-grade carcinoma.86–88

Recent molecular and phenotypic studies suggest a

possible linkage between AAH and carcinoma in the

minority of cases.89,90

While circumstantial evidence exists, there is lack

of proof of a relationship between AAH and

adenocarcinoma.9 It has been suggested that AAH

is a precursor of some low-grade transition zone

carcinomas but the lack of an increased prevalence

of AAH in prostate glands with transition zone

carcinoma argues against this hypothesis.9 Clearly,

there is less evidence linking AAH to carcinoma

than there is for high-grade PIN and cancer.9,75

The major importance of AAH is its potential

for being misdiagnosed as adenocarcinoma. Foci

of AAH are usually less than 5mm across and

are characterized by a proliferation of relatively

small uniform acini, often within or adjacent to

typical hyperplastic nodules (Figure 17). Sometimes

there is a prominent perinodular distribution

of the abnormal glands. The low-power architecture

is reminiscent of Gleason patterns 1 and 2 carcinoma.

AAH usually has a pushing rather than

infiltrating border but may show a limited degree

of infiltration (Figure 18). Individual glands

are closely packed but separate and show no

evidence of fusion. They show some variation in

size and shape and are lined by cuboidal to low

columnar cells with moderate to abundant clear or

lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm. Basal cells are

usually recognized at least focally. The luminal

borders are often irregular and somewhat serrated

in contrast to the rigid borders that typify small

acinar carcinoma. The lumens are often empty

but may contain corpora amylacea and in some

instances luminal eosinophilic crystalloids.74,81

Occasionally, basophilic luminal mucus may be

seen.91,92 There is usually no stromal response but

occasionally, a fibroblastic response is identified

which leads to overlap with the pattern of sclerosing

adenosis.59–63

The nuclei of atypical adenomatous hyperplasia

are round to oval and there is uniform fine

chromatin.74 Nucleoli may be present but they are

generally small. Uncommonly, enlarged nucleoli

(41 mm) are identified in a subset of cells.74

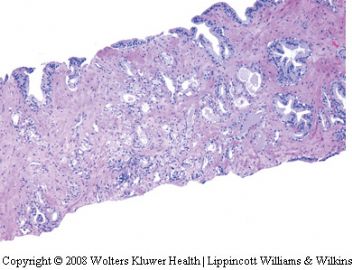

By immunohistochemistry, the glands of AAH

exhibit strong positivity for PSA and PAP and there

is typically a discontinuous basal cell pattern with

the 34bE12 stain (Figure 17).

The most important features in separating AAH

from adenocarcinoma is the lack of significantly

enlarged nucleoli and the presence of a fragmented

basal cell layer. A comparison between high- and

low-grade carcinoma is shown in Table 4.

From a clinical perspective, AAH should be

considered as a benign lesion and patients followed

conservatively. The term should not be used as a

‘wastebasket’ for small glandular lesions that are

difficult to classify or for suspicious atypical small

gland proliferations (atypical small acinar proliferation

[ASAP], glandular atypia), just below the

threshold of adenocarcinoma.9

Large Gland Pattern

Clear cell cribriform hyperplasia

Benign nodular hyperplasia occasionally displays

areas of prominent cribriform glands. Rarely, the

cribriform process dominates the histologic picture.

93,94 Cribriform hyperplasia is characterized by

a crowded proliferation of complex glands without

cytologic atypia. In most instances, the cribriform

glands have clear cytoplasm and uniform round

lumina. This lesion generally has a low-power

nodular appearance and intervening cellular stroma

is seen (Figure 19). The cells comprising the central

cribriform areas are cuboidal to low columnar

secretory-type cells with uniform round nuclei and

clear cytoplasm. They lack nuclear atypia and

nucleolar enlargement. Basal cells are prominently

displayed around the periphery.

Cribriform hyperplasia enters the differential

diagnosis of both prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia

and cribriform adenocarcinoma. The distinction of

cribriform hyperplasia from cribriform carcinoma is

based on the ‘low power’ nodularity, cellular stroma,

presence of basal cells and lack of significant

cytologic atypia.

Adenoid cystic-like basal cell hyperplasia

While most forms of basal cell hyperplasia are

characterized by relatively small nests of basal cells,

the incomplete form of basal cell hyperplasia may be

composed of medium to large glands with a complex

cribriform pattern, sometimes with cyst formation

and squamous metaplasia.9,52,95,96 Such a process

rarely enters the differential diagnosis of cribriform

carcinoma. Some of these cases have been termed

adenoid basal cell tumor or even basal cell carcinoma

(Figure 20). The presence of typical areas of basal

cell hyperplasia, lack of significant infiltration

and absence of cytological atypia favor adenoid

cystic-like basal cell hyperplasia over cribriform

carcinoma.

Reactive atypia in large glands

Medium to large glands may display reactive atypia

in the setting of inflammation, ischemia and radiation.

9,43–45 Such processes may lead to glandular

distortion and nuclear atypia which sometimes

results in a pattern that may be confused with

prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) and large

gland patterns of adenocarcinoma. The most helpful

features to distinguish reactive atypia from

malignancy is the recognition of the associated

inciting factor such as inflammation, infarction

or radiation, and the maintenance of the basal

cell compartment. The atypia associated with

reactive conditions may result in nuclei that

appear hyperchromatic and somewhat degenerate.

In some cases, the nucleolar enlargement associated

with the reactive state may be more prominent

and more uniform than that seen with

adenocarcinoma. The low-power architecture and

presence of a residual basal cell layer sometimes

requiring confirmation with the 34bE12 stain

are the best clues to the benign nature of this

condition.

Fused Gland Pattern

Paraganglion

Paraganglionic tissue may be encountered within

prostatic and periprostatic tissue, usually the latter.

97–99 Paraganglia are characterized by small, solid

nests of cells with clear or amphophilic cytoplasm,

often with a ‘zellballen’ arrangement. There is a

delicate background network of capillaries. The

nuclei are often hyperchromatic but nucleoli and

other features of adenocarcinoma are not seen. The

islands of paraganglionic tissue are separated by

fibrous stroma. Paraganglionic tissue can simulate

the fused gland pattern of adenocarcinoma (Gleason

4) (Figure 21). If the cytoplasm of the paraganglionic

tissue is amphophilic, it may look like Gleason

pattern 4A and if clear may look like Gleason pattern

4B. Cases in needles biopsies are quite rare. A more

common issue is the overinterpretation of extraprostatic

paraganglionic tissue in radical prostatectomy

specimens leading to spurious overstaging of organconfined

cancer. Additionally, the interpretation of

paraganglionic tissue as adenocarcinoma may lead

to a grading inaccuracy. When a Gleason grade 3

tumor is encountered and accompanying paraganglionic

tissue is interpreted as Gleason grade 4

tumor, the resultant score would be inaccurately

Figure 20 Adenoid cystic-like basal cell hyperplasia. (a) Lowpower

photomicrograph showing a rounded collection of large

basaloid nests embedded in loose stroma. (b) Medium-power

photomicrograph showing proliferation of basaloid nests and

cribriform structures with focal dense amorphous material.

recorded as 7 instead of the correct score of 6. In

problematic cases, special stains determining prostatic

origin (PSA, PAP) and stains for neuroendocrine

cells (chromogranin, synaptophysin) should

be employed (Figure 21).

Xanthogranulomatous prostatitis (xanthoma)

Collections of lipid-laden macrophages in the

prostate may cause diagnostic confusion with the

hypernephroid pattern of adenocarcinoma (Gleason

4B)100,101 (Figure 22). Xanthomatous histiocytes

usually have small uniform nuclei within inconspicuous

nucleoli and are commonly admixed with

other types of inflammatory cells. In some instances,

there is almost a pure population of foam cells

which can lead to considerable diagnostic confusion.

The problem is compounded by the fact that

some hypernephroid carcinomas do not show the

typical nuclear features of malignancy. They may

have small dark nuclei without prominent nucleoli.

In rare cases, immunohistochemistry utilizing stains

for epithelial and prostatic cells (cytokeratin, PSA,

PAP) and histiocytes (CD68) is required to resolve

the diagnostic confusion.

Malakoplakia

Malakoplakia of the prostate is a rare infiltrative

lesion characterized by diffuse sheets of histiocytes,

usually admixed with other inflammatory cells

including lymphocytes, plasma cells and neutrophils.

102–106 In the early phase of malakoplakia when

von Hansemann histiocytes predominate, the lesion

may simulate carcinoma, especially Gleason pattern

4B. The lack of any acinar differentiation and

admixed inflammatory infiltrate along with the

typical Michaelis–Gutmann bodies will lead to a

correct diagnosis (Figure 23). The absence of

cytokeratins and prostatic epithelial markers along

with the presence of CD68 staining may resolve

difficult diagnostic problems.

Solid Pattern

Ordinary prostatitis

Occasionally, needle biopsies with prostatitis of the

usual type may cause diagnostic problems.107–109

This is especially true when there is poor preservation

and mechanical (crush) artifacts (Figure 24). In

some cases, immunohistochemical stains (keratins,

Figure 21 Prostatic paraganglion. (a) Needle biopsy showing

solid amphophilic area. (b) High-power photomicrograph showing

rounded amphophilic cellular mass without significant

atypia. (c) Positive chromogranin stain.

leukocyte common antigens) are required in order to

resolve a differential diagnosis.

Non-specific granulomatous prostatitis

Granulomatous prostatitis commonly results in a

prostate gland that feels firm to hard and clinically

simulates carcinoma.110,111 In biopsy samples,

especially needle biopsies, florid nonspecific

granulomatous prostatitis may simulate carcinoma.

112,113 The association of the inflammation

with ducts may not be seen and when the

inflammatory process is diffuse, it may raise the

suspicion of high-grade (Gleason 5) carcinoma

(Figure 25). The problem is amplified if poor

preservation or mechanical artifacts are present.

The recognition of the inflammatory nature of

the cells along with the association of giant cells

and fibrosis are helpful features. In difficult

cases, immunohistochemistry for cytokeratins,

prostatic epithelial markers and lymphohistiocytic

markers may be used (Figure 26). Granulomatous

prostatitis associated with specific infections

such as fungus and tuberculosis, BCG-associated

granulomas and the procedural associated granulomas

(palisading granulomas) do not usually

cause problems in the differential diagnosis of

adenocarcinoma.

Degenerative changes in lymphocytes and stromal

cells

Lymphocytes and sometimes stromal cells may

undergo degenerative changes which result in a

signet ring-like morphology.114–116 If the change is

prominent, the pattern can resemble high-grade

adenocarcinoma composed of individual signet ring

cells (Figure 27). The artifactual signet ring-like

pattern, while initially described in transurethral

resectates, may be found in needle biopsies. In the

series of 47 cases, these ‘atypical’ cells were

prominent in three cases and rare in 11 cases.115 It

is very important to be aware of this phenomenon

and not to overinterpret such cells as being

malignant. In difficult cases, immunohistochemical

stains can be used to confirm the nonepithelial

nature of the cells.

Summary

There are a wide variety of patterns and processes

that may be confused with one or more of the

diverse patterns of prostatic adenocarcinoma. In

general, recognition of this differential diagnosis

coupled with careful routine microscopy will

lead to a correct diagnosis. In some instances

however, ancillary immunohistochemical studies

aimed at identifying prostatic basal cells (34bE12,

CK5/6, p63), prostatic secretory cells (PSA,

PAP, CD57), neuroendocrine cells (chromogranin,

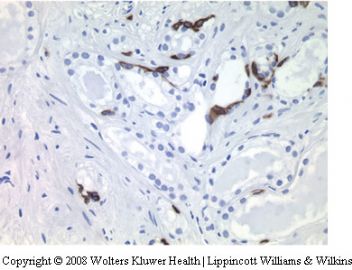

synaptophysin) and inflammatory cells (LCA,

CD68) may be required to resolve a diagnostic

dilemma (see Table 5). The new marker a-methylacyl-

CoA racemase (P504S) appears to be of value

in supporting a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma,

especially when one is dealing with small foci117,118

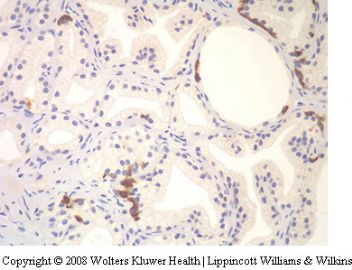

(Figure 28).

Awareness of the differential diagnosis of prostatic

adenocarcinoma is especially important in the

context of diagnosing limited carcinoma in small

biopsy samples. It is important to always be aware of

the potential of false-positive cancer diagnosis when

looking at prostatic biopsies and to utilize appropriate

consultation and ancillary studies to arrive at

a confident and correct diagnosis.

Figure 26 Granulomatous prostatitis (a) Immunohistochemistry

for cytokeratin (CAM 5.2)—note positive glands (upper right) and

negative staining of infiltrate. (b) Infiltrate stains positively for the

macrophage marker, CD68.

Figure 27 Degenerative changes in lymphocytes and stromal cells

simulating signet ring pattern of prostatic adenocarcinoma.

Table 5 Benign mimickers of adenocarcinoma: useful immunohistochemical

markers

Cytokeratins (general)

AE1/AE3, Cam 5.2, MAK6

Basal cell markers

34bE12, CK5/6, p63

Secretory cell markers

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA), prostatic acid phosphatase

(PAP), CD57

Neuroendocrine markers

Chromogranin, synaptophysin

Lymphohistiocytic markers

Leukocyte common antigen, CD56, CD68

Other markers

a-Methylacyl-CoA racemase (P504S)

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the photographic assistance

of David Charters and the excellent secretarial

support provided by Barbara Jones.

Benign mimickers of prostatic adenocarcinoma

JR Srigley

348

Modern Pathology (2004) 17, 328–348

.........

.........

先放一个查到的文献这里,慢慢学习鉴别要点。

可能主要从年龄、部位、形态学(组织结构、细胞学)、免疫组化等方面。

感谢楼主的病例和老师们的提示和启发。