| 图片: | |

|---|---|

| 名称: | |

| 描述: | |

- 女/42,09-4胸膜 09-9腹膜 10-6肝表面肿块 3次穿刺活检

| 姓 名: | ××× | 性别: | 年龄: | ||

| 标本名称: | |||||

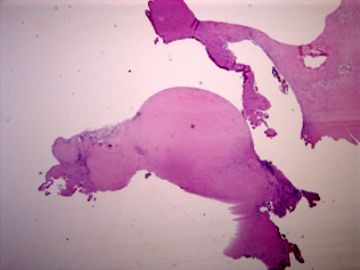

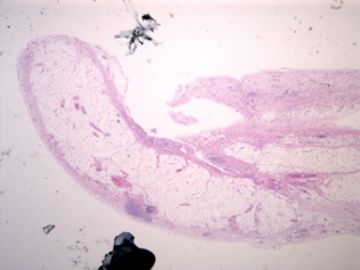

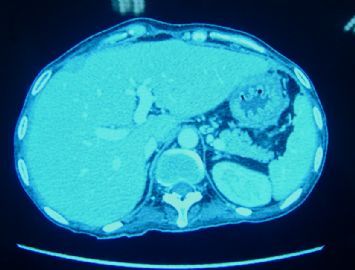

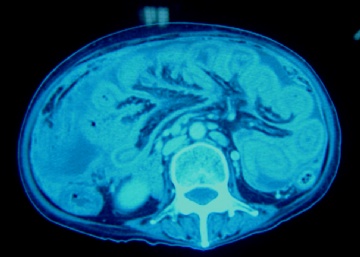

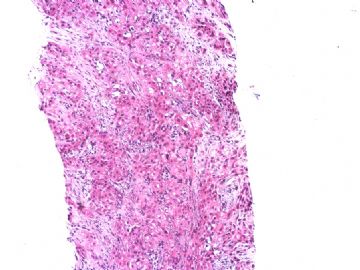

| 简要病史: | 2008-11月起左上腹痛,无腹泻、无发热,少量腹水。腹部CT无占位。妇科检查阴性。对症治疗无好转。胸膜轻度增厚。当地医院行胸腔镜(2009-4)和腹腔镜(2009-9)检查及活检。临床诊断“大网膜脂膜炎”, 用激素及免疫抑制剂治疗。病情渐加重,近二月来腹胀、呕吐、消瘦,并出现恶液质,转入我院。近期CT示肠壁弥漫增厚,肝表面小结节1.5cm。PET/CT示腹腔表面弥漫性高代谢,考虑为炎症性病变可能。 | ||||

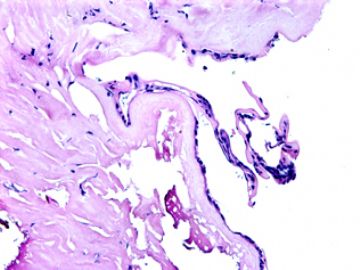

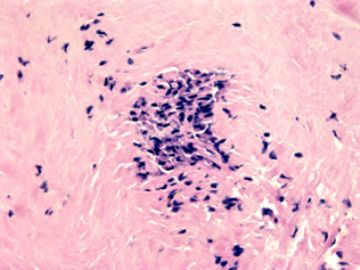

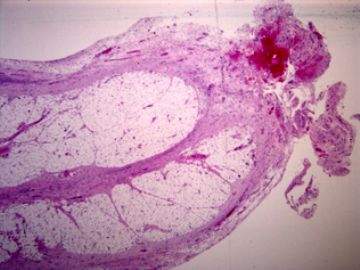

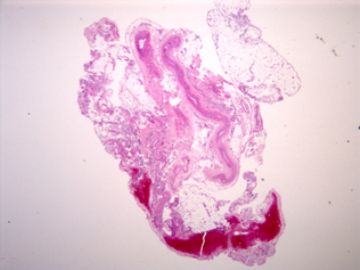

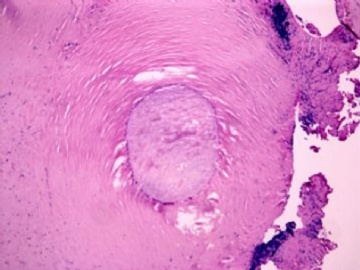

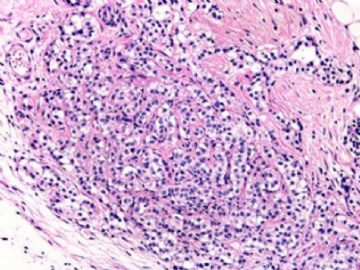

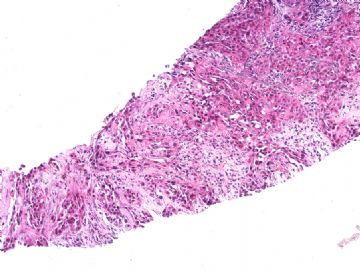

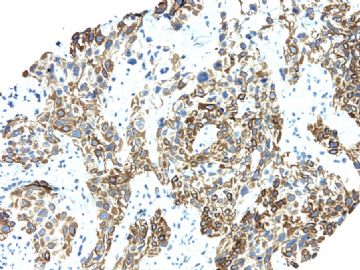

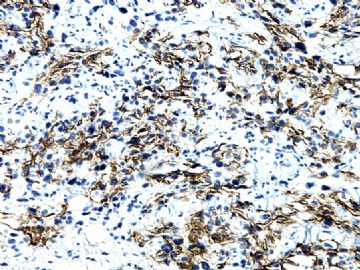

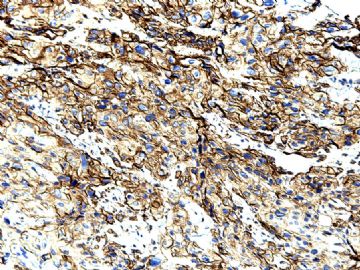

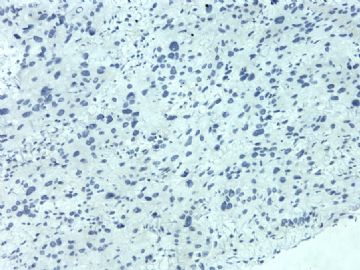

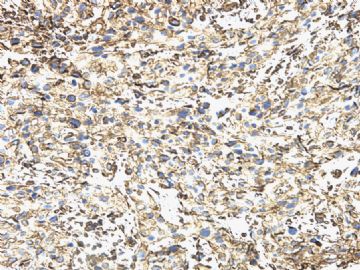

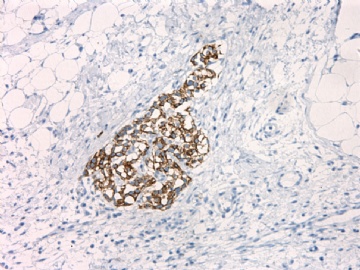

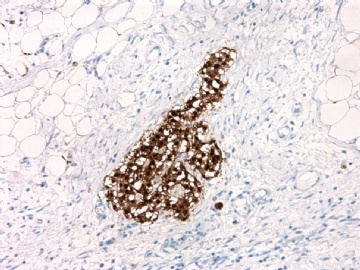

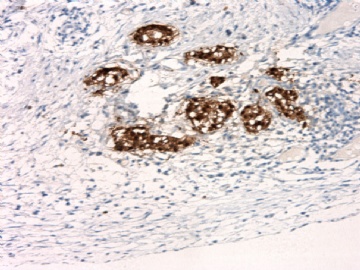

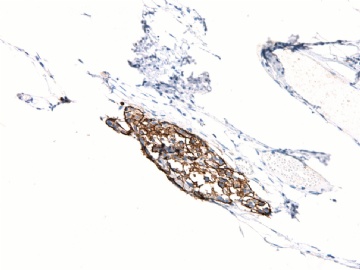

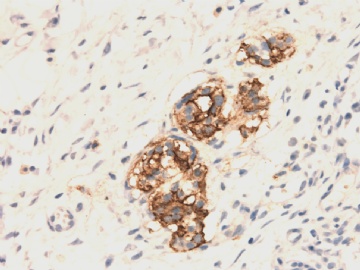

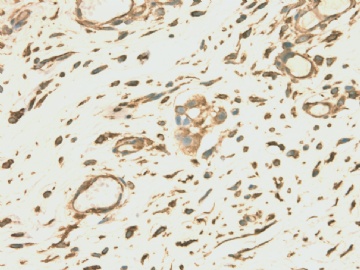

| 肉眼检查: | 胸膜和大网膜活检组织。 外院会诊片:图1-6 胸膜活检;图7-12腹膜活检。 | ||||

-

本帖最后由 于 2010-06-15 07:29:00 编辑

- xljin8

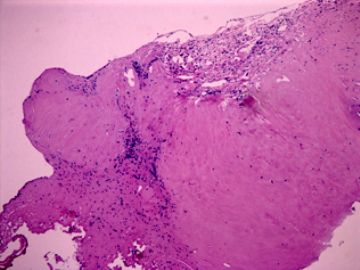

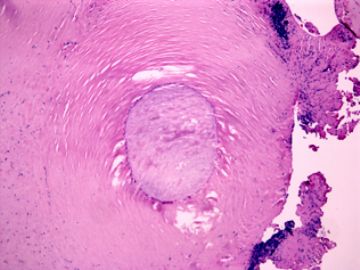

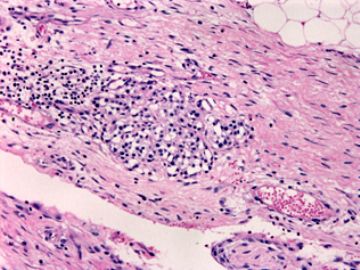

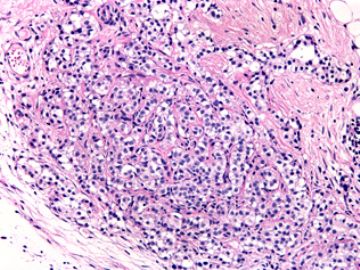

看了文献,感觉到腹膜恶性间皮瘤的诊断是有很多的困难的,翻译加自己的理解,其组织学可以为上皮样、肉瘤样和混合型,其中上皮样型又可以表现为很多病理形态学亚型,如管状乳头状、腺瘤样、腺样、实体状、透明细胞样、小细胞性、印戒细胞样、杆状细胞样等。主要是为其病变的部位为腹膜,在这个部位上有很多的形态学相似的肿瘤需要鉴别,比如以上所述的腺样或管状乳头状的与腹膜的转移性卵巢、胃肠等腺癌的鉴别,还有实体型与间皮细胞增生、实体性腺癌及鳞状细胞癌(丰富粉红胞浆),透明细胞型与肾脏透明癌、肺透明细胞癌、透明细胞黑色素瘤和透明细胞肿瘤的腹膜转移。

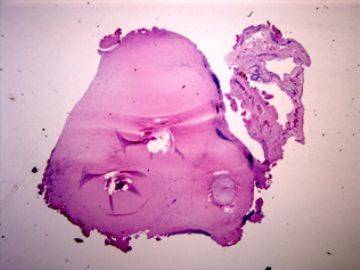

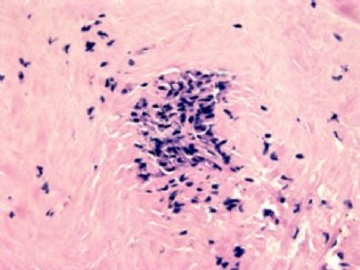

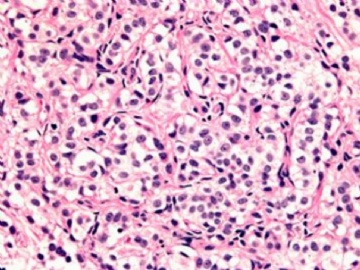

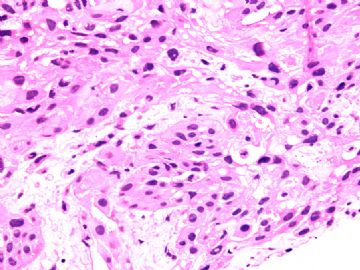

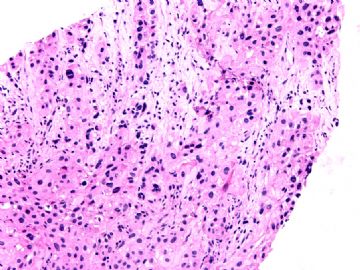

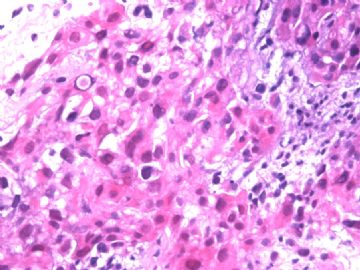

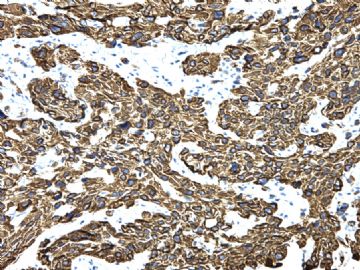

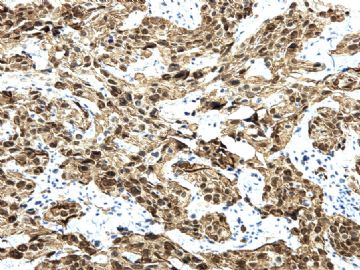

本例腹膜病变主要在肠管的脏层腹膜,为弥漫性分布,肿瘤细胞呈条索样、团块样透明细胞上皮样细胞团,小部分细胞胞浆淡粉染色,肿瘤细胞核圆、形卵形,大小较一致,核仁明显,轻到中度异型性,应当与以上所述的透明细胞样肿瘤鉴别。结合免疫组化及病史,如果能进一步证实肝脏病变属性及肿瘤的腹膜生长的生物学行为,本例倾向于腹膜恶性间皮瘤。

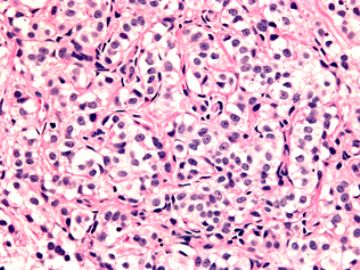

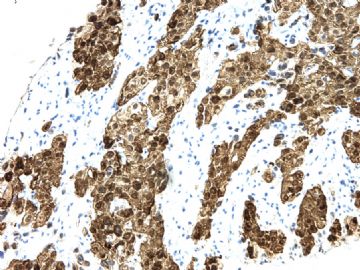

肝脏肿块,形态学为条索状团块样裂隙装嗜酸性胞浆丰富的上皮样肿瘤细胞团,肿瘤细胞核大小不一,圆形椭圆形索性不规则形及畸变样核,中度以上异型性,考虑为上皮性恶性肿瘤,转移性腹膜恶性间皮瘤和肝细胞肝癌鉴别。倾向后者。还须进一步免疫组化证实。

· (学习后,看到,腹膜恶性间皮瘤可能为吸入的石棉纤维入血或石棉纤维尘样通过消化道食入诱发此瘤的发生,附文献一篇,请大家参考)。Abstract

Aliya N. Husain, Thomas V. Colby, Nelson G. Ordóñez, Thomas Krausz, Alain Borczuk, Philip T. Cagle, Lucian R. Chirieac, Andrew Churg, Francoise Galateau-Salle, Allen R. Gibbs, Allen M. Gown, Samuel P. Hammar, Leslie A. Litzky, Victor L. Roggli, William D. Travis, Mark R. Wick (2009) Guidelines for Pathologic Diagnosis of Malignant Mesothelioma: A Consensus Statement from the International Mesothelioma Interest Group. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine: Vol. 133, No. 8, pp. 1317-1331.

REVIEW ARTICLES

Guidelines for Pathologic Diagnosis of Malignant Mesothelioma: A Consensus Statement from the International Mesothelioma Interest Group

Aliya N. Husain, MD, Thomas V. Colby, MD, Nelson G. Ordóñez, MD, Thomas Krausz, MD, Alain Borczuk, MD, Philip T. Cagle, MD, Lucian R. Chirieac, MD, Andrew Churg, MD, Francoise Galateau-Salle, MD, Allen R. Gibbs, MBChB, FRCPath, Allen M. Gown, MD, Samuel P. Hammar, MD, Leslie A. Litzky, MD, Victor L. Roggli, MD, William D. Travis, MD, and Mark R. Wick, MD

From the Department of Pathology, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois (Drs Husain and Krausz); the Department of Pathology, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Scottsdale, Arizona (Dr Colby); the Section of Immunocytochemistry, Department of Pathology, The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston (Dr Ordóñez); the Department of Pathology, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, New York (Dr Borczuk); the Department of Pathology, The Methodist Hospital, Houston, Texas (Dr Cagle); the Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (Dr Chirieac); the Department of Pathology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada (Dr Churg); Groupe Mesopath, Laboratoire d'Anatomie Pathologique, Caen, France (Dr Galateau-Salle); the Department of Histopathology, Llandough Hospital, Penarth, South Glamorgan, United Kingdom (Dr Gibbs); the Department of Pathology, PhenoPath Laboratories, Seattle, Washington, and the Department of Pathology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada (Dr Gown); Diagnostic Specialties Laboratory, Bremerton, Washington (Dr Hammar); Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia (Dr Litzky); the Department of Pathology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina (Dr Roggli); the Department of Pathology, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York (Dr Travis); and the Department of Pathology, University of Virginia Medical Center, Charlottesville (Dr Wick)

|

Abstract |

Context.—Malignant mesothelioma (MM) is an uncommon tumor that can be difficult to diagnose.

Objective.—To develop practical guidelines for the pathologic diagnosis of MM.

Data Sources.—A pathology panel was convened at the International Mesothelioma Interest Group biennial meeting (October 2006). Pathologists with an interest in the field also contributed after the meeting.

Conclusions.—There was consensus opinion regarding (1) distinguishing benign from malignant mesothelial proliferations (both epithelioid and spindle cell lesions), (2) cytologic diagnosis of MM, (3) key histologic features of pleural and peritoneal MM, (4) use of histochemical and immunohistochemical stains in the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of MM, (5) differentiating epithelioid MM from various carcinomas (lung, breast, ovarian, and colonic adenocarcinomas and squamous cell and renal cell carcinomas), (6) diagnosis of sarcomatoid mesothelioma, (7) use of molecular markers in the differential diagnosis of MM, (8) electron microscopy in the diagnosis of MM, and (9) some caveats and pitfalls in the diagnosis of MM. Immunohistochemical panels are integral to the diagnosis of MM, but the exact makeup of panels used is dependent on the differential diagnosis and on the antibodies available in a given laboratory. Immunohistochemical panels should contain both positive and negative markers. The International Mesothelioma Interest Group recommends that markers have either sensitivity or specificity greater than 80% for the lesions in question. Interpretation of positivity generally should take into account the localization of the stain (eg, nuclear versus cytoplasmic) and the percentage of cells staining (>10% is suggested for cytoplasmic membranous markers). These guidelines are meant to be a practical reference for the pathologist.

Accepted: October 16, 2008

Reprints: Aliya N. Husain, MD, University of Chicago, Rm S627, 5841 S Maryland Ave, MC6101, Chicago, IL 60631 (ahusain@bsd.uchicago.edu or aliya.husain@uchospitals.edu)

As part of the International Mesothelioma Interest Group biennial meeting held in Chicago (October 2006), there was a pathology half-day workshop that included invited lecturers and an open forum on the pathologic diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma (MM). The discussion focused on practical diagnostic guidelines meant to be a reference for the pathologist, rather than a mandate or review of the literature. This article is the result of that discussion with additional input from other pathologists who could not attend the meeting.

|

GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS |

The diagnosis of MM must always be based on the results obtained from an adequate biopsy in the context of appropriate clinical, radiologic, and surgical findings. A history of asbestos exposure should not be taken into consideration by the pathologist when diagnosing MM. Location of the tumor (pleural vs peritoneal) as well as the sex of the patient will affect the differential diagnosis as discussed later. Specific information on antibody clones and their source should be obtained from the current literature because this an evolving area and is outside of the scope of this article.

|

BENIGN VERSUS MALIGNANT MESOTHELIAL CELL PROLIFERATIONS |

Separating benign versus malignant mesothelial proliferations presupposes first that the process has been recognized as mesothelial. The diagnostic approach used when distinguishing reactive mesothelial hyperplasia from epithelioid mesothelioma is different from that used when distinguishing fibrous pleuritis from desmoplastic mesothelioma.1 The major problem areas are discussed in the following.

Reactive Mesothelial Hyperplasia Versus Epithelioid MM

It is well known that reactive mesothelial proliferations may mimic mesothelioma (or metastatic carcinoma). Some of the causes of reactive mesothelial hyperplasia in the pleural space include infections, collagen vascular diseases, pulmonary infarcts, drug reactions, pneumothorax, subpleural lung carcinomas, surgery, trauma, and nonspecific inflammation. Exuberant mesothelial reactions also are encountered in the peritoneum and pericardium, and the latter may be particularly worrisome.

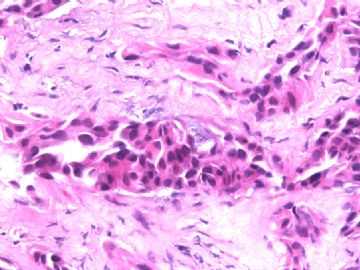

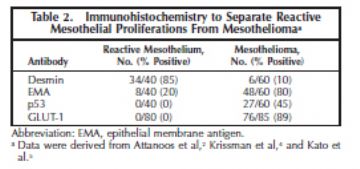

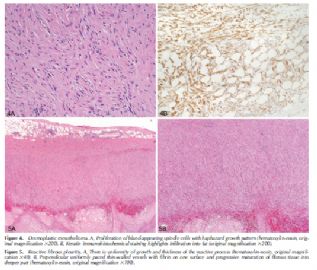

The specific features of a reactive mesothelial proliferation that may mimic a neoplasm include high cellularity, the presence of numerous mitotic figures and cytologic atypia, the presence of necrosis, the formation of papillary groups, and entrapment of mesothelial cells within fibrous tissue mimicking invasion (Figure 1). Features distinguishing reactive mesothelial hyperplasia from mesothelioma are summarized in Table 1.

Demonstration of stromal or fat invasion is the key feature in the diagnosis of MM (Figure 2). Invasion may be into visceral or parietal pleura (or beyond) and this can be highlighted with immunostains such as pancytokeratin or calretinin. Invasion by mesothelioma is often subtle and may be into only a few layers of collagenous tissue below the mesothelial space. Invasive mesothelial cells may also be deceptively bland in appearance and completely lack a desmoplastic reaction. However, it is emphasized that if a solid piece of malignant tumor, with histologic features of MM, is identified, the presence of invasion is not required for the diagnosis.

Reactive mesothelial proliferations tend to show a uniformity of growth and this may be highlighted with pancytokeratin staining, which show regular sheets and sweeping fascicles of cells that respect mesothelial boundaries in contrast to the disorganized growth and haphazardly intersecting proliferations seen in mesothelioma.

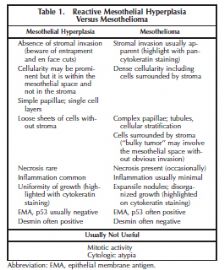

Although certain immunohistochemical stains are more typically positive in benign proliferations and others in malignant proliferations, they should not be solely relied on for diagnosis in individual cases. The best known of these include epithelial membrane antigen, p53, and desmin. The results of Attanoos et al,2 who studied 60 mesotheliomas and 40 cases of reactive mesothelial hyperplasia, are included in Table 2. This topic was reviewed by King et al3 who concluded that desmin and epithelial membrane antigen (membranous staining) were the most useful but that the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for both was less than 90%. They noted that novel markers of proliferation such as MCM2 and AgNOR may be useful adjuncts in this situation but they present technical difficulties and are not widely used. Although telomerase transcriptase expression was suggested to discriminate between hyperplastic and neoplastic mesothelium, subsequent studies showed limited usefulness.4

In a recent study by Kato et al,5 GLUT-1 reactivity was found in 40 of 40 mesotheliomas; whereas all 40 cases of reactive mesothelium were negative. A study done at the University of Chicago6 showed all 40 benign mesothelial tissues (20 normal, 20 reactive cases) to be negative for GLUT-1, whereas of 45 MM, 9 (20%) were negative, 34 (53%) were weakly positive, and 12 (27%) were strongly positive. Thus, when GLUT-1 is positive, it is a helpful marker for MM, both epithelioid and sarcomatoid (Figure 3, A through D), but is not helpful when negative.

Fibrous Pleurisy Versus Desmoplastic Variant of Sarcomatoid Mesothelioma

The identification of features of malignancy in a desmoplastic mesothelioma requires adequate tissue and the amount of tissue in a closed pleural biopsy is often insufficient. Large surgical biopsies are generally needed. High-grade sarcomas presenting in the pleura generally do not enter into the differential diagnosis of fibrous pleurisy versus desmoplastic mesothelioma. Features to separate the latter two are shown in Table 3.

In the study by Mangano et al,7 the distinction of fibrous pleurisy from desmoplastic mesothelioma could be made by identifying one or more of the following features in a spindle cell proliferation of the pleura: invasive growth, bland necrosis, frankly sarcomatoid areas, and metastatic disease.

Stromal invasion is often more difficult to recognize in spindle cell proliferations of the pleura than in epithelioid proliferations. The invasive malignant cells are often deceptively bland, resembling fibroblasts, and pancytokeratin staining is invaluable in highlighting the presence of cytokeratin-positive malignant cells in regions where they should not normally be present: in the connective tissue, adipose tissue, or skeletal muscle deep to the parietal pleura or invading the visceral pleura and lung tissue (or other extrapleural structures present in the sample) (Figure 4, A and B). Although Mangano et al7 also found bland necrosis of paucicellular fibrous tissue to be a reliable criterion of malignancy, it may be subtle and one may be reluctant to base a diagnosis of malignancy solely on its presence. Fortunately, most cases that show bland necrosis also show invasive growth. Similarly, the presence of “frankly sarcomatoid foci” is a distinctly subjective determination and one would be reluctant to base a diagnosis of malignancy on its presence alone because reactive processes may show marked cytologic atypia, albeit typically at the surface of the process.

Uniformity of growth and thickness of the process, surface atypia with deep maturation, and perpendicular thin-walled vessels are typical of reactive fibrous pleuritis (Figure 5, A and B), in contrast to the disorganized growth pattern and variable thickness of desmoplastic mesotheliomas. A helpful clue in desmoplastic mesotheliomas is the presence of expansile nodules of varying sizes with abrupt changes in cellularity between nodules and their surrounding tissue.

|

CYTOLOGIC FEATURES OF MM |

There is limited role of cytology in the primary diagnosis of MM, but this is debated between cytopathologists and surgical pathologists. The diagnosis of MM has to be made with certainty, and the International Mesothelioma Interest Group panel recommends that a cytologic suspicion of MM be followed by tissue confirmation that must be supported by both clinical and radiologic data.

Many of the cytologic features (scalloped borders of cell clumps, intercellular windows, with lighter dense cytoplasm edges, and low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios) are shared between reactive and malignant epithelioid mesothelial cells. Usually the malignant cells in sarcomatoid MM are not shed into the effusion fluid, which may contain the overlying reactive epithelioid mesothelial cells that may mislead the pathologist.

The most useful cytologic features of MM (Figure 6, A through D) are

· The presence of numerous relatively large (>50 cells) balls of cells with berrylike external contours is characteristic of MM. The cells are much larger as compared with the average mesothelial cells. This includes enlargement of cytoplasm, nucleus, and nucleolus.8

· The presence of macronucleoli. However, prominent nucleoli can be present in reactive mesothelial cells and not all MM cells have macronucleoli.

· Nuclear atypia is helpful, if present.

Key cytologic features of adenocarcinoma are

· Clumps of cells are present usually having smooth rather than berrylike borders.

· The nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio is usually higher than in MM.

· Nuclear variability in shape and size is much more common.

· Cytoplasmic vacuoles often contain epithelial mucin in contrast to mesothelial cells that contain hyaluronic acid.

· Cytoplasm is less dense than in mesothelial cells, and “windows” are rarely present.

· Psammoma bodies (when present) are more likely to be a feature of adenocarcinoma than MM, but they do occur in MM.

· Use of immunohistochemistry in cytologic specimens is similar to that in tissue sections (see later).

|

HISTOLOGIC FEATURES OF MM |

Most MMs are readily identified or strongly suspected on routine hematoxylin-eosin histology in which they exhibit a variety of histologic patterns, broadly divided into epithelioid, sarcomatoid, or mixed (biphasic) categories. Epithelioid MMs are composed of polygonal, oval, or cuboidal cells that often mimic nonneoplastic reactive mesothelial cells. Sarcomatoid MMs consist of spindle cells, and mixed or biphasic MMs contain both epithelioid areas and sarcomatoid areas within the same tumor.9–15

In general, the differential diagnosis for MM depends on its basic histologic category: the differential diagnosis for epithelioid MM includes carcinomas and other epithelioid cancers, the differential diagnosis for sarcomatoid MM includes sarcomas and other spindle cell neoplasms, and the differential diagnosis of mixed MM includes other mixed or biphasic tumors such as synovial sarcoma. Desmoplastic mesotheliomas may mimic fibrous pleuritis. Because each broad histologic category has its own distinctive differential diagnosis, the immunostains selected for further workup of a MM are dictated by the histologic category into which it falls.9–16

The most common histologic type of MM is epithelioid. The common secondary patterns of epithelioid MM are readily recognized by most pathologists: tubulopapillary pattern, acinar (glandular) pattern, adenomatoid pattern (also termed microglandular), and the solid mesothelial-cell pattern. Some epithelioid MMs have a distinctive recognizable secondary pattern consisting of clusters of epithelioid cells floating in pools of hyaluronic acid. The clear cell, deciduoid, adenoid cystic, signet ring, small cell, and rhabdoid patterns are less common secondary patterns of epithelioid MM that are more likely to be confused with other types of cancer.

The tubulopapillary pattern, acinar (glandular) pattern, and adenomatoid (microglandular) pattern must be differentiated from adenocarcinoma metastatic to the pleura. The tubulopapillary pattern consists of a mixture of papillary structures lined by bland flat, cuboidal, or polygonal cells with fibrovascular cores and glandlike tubules. The acinar pattern consists of elongated or branching glandlike lumina lined by relatively bland cuboidal cells. The adenomatoid pattern consists of bland flat to cuboidal cells lining small glandlike structures.

The solid pattern consists of nests, cords, or sheets of round, oval, or polygonal cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and round, vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli. These cells resemble nonneoplastic, reactive mesothelial cells, and the differential diagnosis may include reactive mesothelial hyperplasia, solid adenocarcinoma, and even squamous cell carcinoma due to the abundant pink cytoplasm. The solid poorly differentiated pattern consists of sheets and nests of relatively discohesive polygonal to round cells with uniform nuclei. Lymphomas and poorly differentiated carcinomas enter into the differential diagnosis of solid poorly differentiated MM.9–15

The clear cell pattern is composed of MM cells with clear cytoplasm that should be differentiated from clear cell renal cell carcinomas, clear cell carcinomas of the lung, clear cell melanoma, and other clear cell tumors that can metastasize to the pleura.17–19

The deciduoid pattern is composed of sheets of large, round to polygonal cells with sharp cell borders, abundant glassy eosinophilic cytoplasm, and round vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli.

The adenoid cystic pattern consists of cribriform and tubular patterns separated by fibrous stroma and the differential diagnosis includes adenoid cystic carcinoma in addition to adenocarcinoma. The signet ring or lipid-rich pattern consists of clusters or sheets of MM cells that contain cytoplasmic vacuoles and these rare tumors should be differentiated from metastatic signet ring cell adenocarcinoma.20 The extremely rare small cell pattern of MM consists of uniform small, round cells with bland nuclei and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. The rhabdoid pattern is characterized by the presence of discohesive cells having abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, an eccentric nucleus with a prominent nucleolus, and a rounded, eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusion that sometimes causes nuclear indentation. The proportion of the rhabdoid component in these tumors ranges from 15% to 75%.21

Secondary patterns of sarcomatoid MM may demonstrate anaplastic and giant cells with a differential diagnosis of malignant fibrous histiocytoma, osteosarcomatous areas with a differential diagnosis of osteosarcoma, or chondrosarcomatous areas with a differential diagnosis of chondrosarcoma.22–24

The lymphohistiocytoid pattern consists of discohesive, atypical histiocytoid-appearing MM cells within an intense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. The differential diagnosis includes nonneoplastic inflammatory process, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and Hodgkin lymphoma.25,26

Most desmoplastic MM are sarcomatoid MM, although occasional epithelioid desmoplastic MM can occur. A paucicellular distribution of bland neoplastic spindle cells between bands of dense collagenous stroma that resemble pleural plaque is the distinguishing feature of desmoplastic MM. This type of MM may not be suspected unless frankly sarcomatoid areas of the tumor are found. This pattern is discussed further later.9–15 When prominent neoplastic giant cells or anaplastic cells are present (pleomorphic MM), pleomorphic carcinoma and other high-grade, poorly differentiated neoplasms metastatic to the pleura should be excluded.

|

MORPHOLOGIC FEATURES RELATED TO PERITONEAL MM |

The morphology of peritoneal malignant mesothelioma (PMM) is similar to that of pleural MM in that there are epithelioid and sarcomatous patterns and the epithelioid patterns include common tubulopapillary/papillary and solid histologies. In the peritoneum, however, several site-specific issues are recognized.

Although epithelioid and sarcomatous patterns can be seen in PMM, the incidence of biphasic tumors is lower than in pleural disease, and pure sarcomatous tumors are very rare.27,28 This observation in PMM is of importance as the biphasic subgroup has a significantly poorer prognosis and is less amenable to treatment overall.29,30 Although definitions of pleural MM have proposed a minimum of 10% spindled growth for a biphasic designation, the less common occurrence of biphasic histology and the distinctly poorer prognosis of this group in PMM may make a minimum value less practical. It remains unclear whether identification of any component of malignant spindled histology portends a poor prognosis in PMM.31

Multiple mesothelial-lined cysts, also known as benign multicystic mesothelioma, represent a rare but well-described entity that may enter the differential diagnosis of mesothelial neoplasia. This lesion is nearly always encountered in the peritoneum, although rare cases with pleural involvement have been described. These cystic proliferations are lined by bland mesothelial cells and lack stratification, papillation, or atypia. If defined in this fashion, this process does not metastasize but can recur.32

Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma is also an important subgroup much more frequently encountered in the peritoneum. These generally noninvasive papillary neoplasms are lined by bland mesothelial cells with low-grade nuclei. These nuclei are small, smooth contoured and do not contain nucleoli. Mitoses are rarely present. When narrowly defined, this tumor has an excellent prognosis, although recurrent disease can be problematic. Because the natural history of this subgroup is distinct from PMM, it is an important morphologic distinction from architecturally similar but more aggressive papillary epithelioid mesotheliomas.33,34

|

HISTOCHEMICAL STAINING IN MM |

The cytoplasmic vacuoles in adenocarcinomas frequently contain epithelial mucin highlighted by periodic acid– Schiff after digestion and mucicarmine stains. Epithelial mucin can also be positive by Alcian blue, but it is not digested by hyaluronidase. Although it has been generally accepted that MM do not show periodic acid-Schiff after digestion–positive vacuoles as seen in adenocarcinomas, there are rare well-documented examples of epithelioid MM that show periodic acid–Schiff after digestion positivity.35 Mesothelial cells may have vacuoles containing hyaluronic acid, positive by Alcian blue and digestible by hyaluronidase. Mucicarmine may also stain hyaluronic acid in MM; thus, mucicarmine stain is not recommended for distinguishing MM from adenocarcinoma.

|

IMMUNOHISTOCHEMICAL STAINING IN MM |

A definitive diagnosis of MM requires a workup including immunohistochemistry and in some cases histochemical stains for mucin. The role of immunohistochemistry varies depending on the histologic type of mesothelioma (epithelioid versus sarcomatoid), the location of the tumor (pleural versus peritoneal), and the type of tumor (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, malignant melanoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma) being considered in the differential diagnosis.

This section deals with pleural mesothelioma as peritoneal mesotheliomas are dealt with in a separate section. The immunohistochemical approach is different depending on whether the tumor is sarcomatoid or epithelioid. Because biphasic mesotheliomas have an epithelioid component, the differential diagnosis is similar to that of epithelioid mesotheliomas.

Immunohistochemical staining for pancytokeratin is useful in the diagnosis of mesothelioma because virtually all tumors will be positive. Rare exceptions are some sarcomatoid mesotheliomas, particularly those with osteosarcomatous differentiation, which may be keratin negative. If an epithelioid malignant neoplasm causing diffuse pleural thickening is keratin negative with pancytokeratin immunostaining, one should consider other possible differential diagnoses such as malignant melanoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma or angiosarcoma (although some of these can be keratin positive), and malignant lymphoma. In this circumstance, it is recommended that a screening panel be performed to address these possibilities. Such a panel might include CD45 (LCA), CD20 or CD30 for large cell lymphoma, S100 and HMB-45 for melanoma, and CD31 and CD34 for angiosarcoma or epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Because D2-40 will stain epithelioid vascular tumors, it is not a good marker for this differential diagnosis. Further confirmatory staining may be useful if one or more of these screening markers is positive. Ultrastructural studies may be of benefit in particularly difficult cases.

On occasion, a tumor may lack staining with any marker; this may be due to various reasons including poor fixation. Negative immunoreactivity may also occur in alcohol-fixed tissues if antigen retrieval is used, so some knowledge about the fixative is important. If needed, vimentin may be used to assess immunoreactivity.

As the role of immunohistochemistry has evolved, it has become a standard to use panels of positive and negative antibodies that vary depending on the differential diagnosis. Because there is variability of staining between different antibody clones and between separate laboratories, this document does not recommend a specific panel of antibodies. It is best for each laboratory to test staining conditions for the antibodies of choice with appropriate controls. If possible, a sensitivity of at least 80% should be required for the antibodies chosen.

There is no absolute number of antibodies that can be recommended for the diagnosis of MM. Workup can be done in stages. An initial workup could use 2 mesothelial markers and 2 markers for the other tumor under consideration based on morphology (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma). If the results are concordant, the diagnosis may be considered established. If they are discordant a second stage, expanding the panel of antibodies, may be needed. The pattern of immunohistochemical staining is important with certain antibodies such as calretinin, for which both cytoplasmic and nuclear staining is required to support a diagnosis of mesothelioma, and WT-1, which should be only nuclear. There is no standard for the percentage of tumor cells that should be positive, but some have used a 10% cutoff for membranous and cytoplasmic staining.

|

EPITHELIOID MESOTHELIOMA VERSUS CARCINOMA |

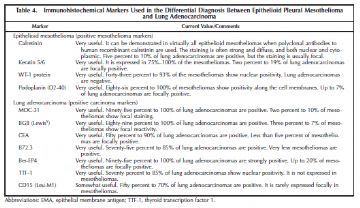

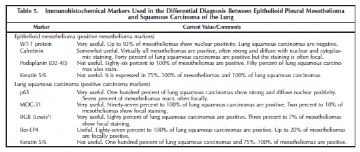

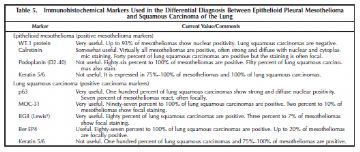

The primary differential diagnosis for epithelioid mesothelioma in the pleura is with metastatic lung carcinoma and is heavily reliant on immunohistochemistry using a battery of mesothelial and carcinoma markers (Tables 4 and 5).14,36 As shown in the tables, the type of carcinoma markers that are useful varies depending on whether the differential diagnosis lies with adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 7, A and B; Figure 8, A and B; Figure 9, A through C; Figure 10, A and B; Figure 11, A through C; Figure 12; Figure 13).

The International Mesothelioma Panel recommends that at least 2 mesothelial and 2 carcinoma markers be used in addition to a pancytokeratin.14 None of these antibodies are 100% specific and false positives (which often show less than 10% staining) can occur in either direction. The only exception is thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1), for which there is no published case of positive staining with a mesothelioma. The diagnosis is most straightforward when only mesothelioma or carcinoma markers are positive, but in some cases the staining results are conflicting. In such cases it may be useful to expand the panel to include additional markers. If the result continues to be conflicting, electron microscopy may be helpful.14

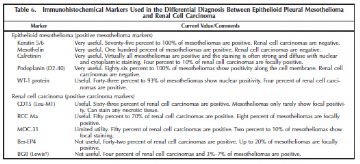

Several special types of metastatic carcinomas are worth addressing including tumors from the breast, kidney, and ovary. The latter is addressed primarily in the section on peritoneal mesothelioma. Most breast carcinomas will express estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, or BRST2 (gross cystic disease fluid protein) in addition to the general carcinoma markers BG8 and MOC-31. Antibodies useful in separating mesothelioma from metastatic renal cell carcinoma are summarized in Table 6.

|

IMMUNOHISTOCHEMICAL ISSUES IN PERITONEAL MESOTHELIOMA |

Diffuse malignancies of the peritoneum include PMM, primary peritoneal carcinoma, and secondary peritoneal carcinomatosis in the clinical, imaging, and gross pathologic differential diagnosis in many cases. In pleural disease, pseudomesotheliomatous carcinoma (defined as a carcinoma that grows along pleura encasing the lung) is most often from an adenocarcinoma of pulmonary origin, whereas peritoneal carcinomatosis can be of ovarian, gastric, pancreatic, colonic, and, more rarely, breast origin.27,37 Therefore, immunohistochemistry panels have to be adjusted accordingly. An examination of markers frequently positive in mesothelioma have to be assessed in comparison to gastric, pancreatic, and colon carcinoma in both genders and, additionally, in comparison to ovarian carcinoma and, more rarely, lobular breast carcinoma in women.

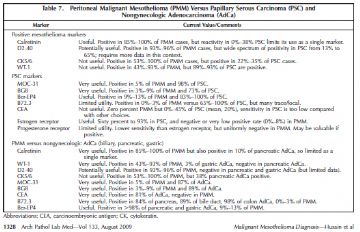

Most studies have focused on differentiating PMM from papillary serous carcinoma (PSC) and these are summarized in Table 7. There have been less data directly comparing the profile of PMM to pancreatic, gastric, and colon carcinoma. This direct comparison is more relevant in male patients in whom ovarian and primary serous carcinomas do not occur (Table 7).

In summary, the markers useful in female patients include calretinin and possibly D2-40 (which can also be positive in some cases of PSC) for positive markers in PMM, and MOC-31, BG8, and, with less specificity, Ber-EP4 for positive adenocarcinoma markers. Although specific, B72.3 staining may be too focal in many PSC cases, although a positive result is very useful. The high frequency of reactivity for the mesothelioma markers cytokeratin (CK) 5/6 and WT-1 in PSC and the infrequent staining for carcinoembryonic antigen in PSC limits the ability of those markers to discriminate between these entities. Estrogen receptor may be helpful in difficult cases, as would a positive result for progesterone receptor. In male patients, WT-1 (nuclear staining) and D2-40 are useful markers in addition to calretinin, and for nonserous adenocarcinoma, B72.3, MOC-31, BG8, and Ber-EP4 all have high sensitivity and specificity. In addition, carcinoembryonic antigen may also be useful in the setting when PSC is not in the differential diagnosis. Recently, h-caldesmon has been reported to be highly useful as a mesothelial marker.38

|

SARCOMATOID MESOTHELIOMA |

The criteria for distinguishing reactive fibrous pleurisy from sarcomatoid mesothelioma have been well characterized and were summarized earlier in the article.

An immunohistochemical panel that can be useful for the initial evaluation of a sarcomatoid tumor involving the pleura should include cytokeratins, calretinin, and D2-40. Multiple cytokeratin antibodies including AE1/3, CAM 5.2 (or CK18), and CK7 should be used as cytokeratin expression can be focal, weak, and/or variable.39,40 Other positive markers that are used in the evaluation of epithelioid mesothelioma such as WT-1 and CK5/6, as well as adenocarcinoma markers such as Ber-EP4, carcinoembryonic antigen, and MOC-31, do not provide much added utility in sarcomatoid tumors. D2-40 and calretinin have been the 2 positive mesothelial markers most consistently expressed in sarcomatoid mesotheliomas in a variable percentage of cases.40–42 False positives can occur by the misinterpretation of positive reactivity within benign entrapped lymphatics or reactive mesothelial elements.

A histologically malignant sarcomatoid tumor that is strongly and diffusely cytokeratin positive usually limits the differential diagnosis to sarcomatoid mesothelioma, sarcomatoid carcinoma, and, on occasion, synovial sarcoma or metastatic sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma. Although synovial sarcomas of the pleura (or primary pulmonary synovial sarcomas involving the pleura) usually present as localized solid tumors, they can present with diffuse pleural thickening that is similar to MM. The diagnosis of synovial sarcoma should be considered when there is a highly cellular neoplasm with very little cytoplasm in tumor cells resulting in overlapping nuclei, focal hemangiopericytoma-like blood vessels are present, and there is limited keratin expression. The diagnosis can be confirmed by molecular testing for its distinctive X;18 translocation in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. Unless there is convincing calretinin and D2-40 positivity, it is difficult to separate out the spindled cell component of a partially sampled sarcomatoid carcinoma from sarcomatoid mesothelioma. Heterologous elements may be present in both tumors. A possible distinguishing feature is when the tumor has areas in which the malignant cells are infiltrating through densely collagenized fibrosis (as is characteristic of desmoplastic mesothelioma). This pattern is quite typical of MM and favors that diagnosis, although ultimately, in this instance, the diagnosis may have to incorporate other gross and clinical features. In some cases, especially with limited biopsy material, it may be difficult to distinguish metastatic sarcomatoid carcinoma from sarcomatoid mesothelioma. Carcinoma markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen and thyroid transcription factor 1 (for lung) can be tried. Sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma can metastasize to the pleura and grow like a mesothelioma producing a pseudomesotheliomatous sarcomatoid-type pattern. Differential cytokeratin positivity profiles, other than CK5/6, have not been reported to date in the differential diagnosis of these 2 tumors. CK5/6 has been reported to be negative in sarcomatoid renal cell carcinomas, but the low sensitivity of CK5/6 as a marker in sarcomatoid mesothelioma greatly limits its utility.43 Calretinin and D2-40 positivity have not been extensively studied in sarcomatoid renal cell carcinomas. One series reported calretinin negativity in all 4 sarcomatoid renal cell carcinomas tested, but at this point it would be prudent to incorporate additional gross and clinical correlation.43

A histologically malignant sarcomatoid tumor that is either focally cytokeratin positive or cytokeratin negative should be cautiously interpreted, and a diagnosis of mesothelioma very carefully considered. Focal cytokeratin positivity has been reported in many different types of sarcomas. It is also possible that the focal cytokeratin positivity represents entrapment of benign pleural elements. If the initial round of cytokeratins proves to be negative or there is only focal cytokeratin positivity, additional blocks should be selected and stained, and cytokeratin antigen retrieval techniques as well as antibody source and dilutions should be reviewed. A vimentin stain is useful in assessing the general antigenic integrity of the tissue. Particularly in the absence of convincing cytokeratin positivity, calretinin and/or D2-40 positivity alone should not be interpreted as evidence of mesothelial differentiation. These markers are variably positive in many different types of sarcomas and other immunohistochemical markers should be added at this point. The expanded differential diagnosis might include other sarcomas (epithelioid hemangioendothelioma/angiosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, liposarcoma, myogenic or neurogenic tumors), malignant solitary fibrous tumor, melanoma, and lymphoma. The marker panel should be expanded accordingly to include antibodies such as CD31, CD34, desmin, myoglobin, S100, and LCA. It should be noted that some muscle markers are often positive at least focally, and on occasion more diffusely, in sarcomatoid mesotheliomas.44 These markers include muscle-specific actin (HHF-35) and α smooth muscle actin. Desmin positivity in pure sarcomatoid mesotheliomas is quite rare.44,45 After extensive workup and with appropriate clinical and radiologic features, cytokeratin-negative sarcomatoid mesotheliomas have been published as a diagnosis of exclusion.39,46,47

|

MOLECULAR MARKERS IN MM |

The road to mesothelioma development is known to be long and winding and studies suggest that mesothelioma development is related to complex cytogenetic and molecular events attesting to the long latency period of more than 30 to 40 years and to the multistep process. There are no molecular markers as yet that are useful in confirming a diagnosis of mesothelioma. However, detecting t(X;18) is most useful in the differential diagnosis of synovial sarcoma. Begueret et al48 have confirmed the presence of this translocation in 90% of purely sarcomatoid primary synovial sarcoma of the pleura, whereas this translocation has never been detected in MM.49

|

ELECTRON MICROSCOPY OF MM |

The electron microscopic features of MM are well described.12,50 There is no single ultrastructural feature that is diagnostic of mesothelioma but rather the combination of several features that may be diagnostically useful. For epithelioid mesotheliomas these include very long thin apical microvilli that do not have a glycocalyx, as opposed to the generally shorter microvilli of adenocarcinomas that usually do have a glycocalyx; perinuclear tonofilament bundles; the presence of basal lamina; and long desmosomes.

Electron microscopy is most valuable for well to moderately well differentiated epithelioid tumors because sarcomatous mesotheliomas typically do not show mesothelial features. It may also be very useful in establishing the correct diagnosis when the immunohistochemical results are equivocal or further support of a diagnosis of either MM or serous carcinoma is needed.51 Formalin-fixed material retrieved from a paraffin block can sometimes be useful because microvilli and tonofilament bundles tend to be preserved. However, the limitations of electron microscopy need to be recognized. For one thing there may be considerable overlap of ultrastructural features between adenocarcinomas and epithelioid mesotheliomas. As well, the characteristic ultrastructural features of mesothelioma tend to be seen in tumors for which the diagnosis is obvious by light microscopy; in tumors that are poorly differentiated, electron microscopy usually does not solve the problem.52,53

|

FEATURES NOT USEFUL IN MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS OF MM |

History of Asbestos Exposure

Because there is an association of asbestos exposure and the development of MM, many pathologists may adopt the position that a history of asbestos exposure makes a tumor more likely to be a mesothelioma, and, conversely, in the absence of such a history, they are reluctant to diagnose mesothelioma. However, the history of exposure to asbestos or the absence of such a history is not useful to the pathologist in making a diagnosis of mesothelioma. The situation is analogous to that of lung cancer: Although most lung cancers occur in cigarette smokers, no one would hesitate to diagnose a lung cancer if told that the patient was a nonsmoker. For mesothelioma a similar scenario applies: The diagnosis is based on clinical, radiologic, and, ultimately, pathologic features, and the issue of asbestos exposure is irrelevant.

Presence of Psammoma Bodies

Like many tumors with a papillary architecture, mesotheliomas may occasionally contain psammoma bodies. Although the presence of psammoma bodies might suggest certain carcinomas (eg, papillary carcinoma in the thyroid and serous papillary tumors of the female genital tract and peritoneal surface), their presence is not a diagnostic aid in either confirming or excluding a diagnosis of mesothelioma.

Mucicarmine Positivity

The evaluation of mucin stains in putative mesotheliomas is not straightforward and positivity in a tumor with some mucin stains should not be used as a criterion in confirming or excluding the diagnosis of mesothelioma.

Although the presence of mucin has been classically used to support a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma rather than mesothelioma, mucin positivity may be encountered in mesotheliomas. With Alcian blue and colloidal iron staining mesotheliomas may contain hyaluronate droplets that show a positive reaction and this material is removed with hyaluronidase pretreatment. The spaces containing the positive material tend to be quite large and not typical of the intracellular mucin droplets seen in adenocarcinoma. Because hyaluronidase-sensitive material may be encountered in mesotheliomas, digested periodic acid–Schiff stains have been recommended for neutral (“epithelial”) mucins because this finding is almost entirely restricted to adenocarcinoma. Rarely otherwise typical mesotheliomas may contain mucicarmine-positive, digested periodic acid-Schiff–positive, and Alcian blue–positive droplets that are resistant to hyaluronidase. Ultrastructural evaluation in the small series reported by Hammar et al35 suggested that this positivity was related to crystallized proteoglycans.

A rim of faint mucicarmine positivity is common in the vacuoles of mesotheliomas and should not be considered a feature diagnostic of adenocarcinoma.

SV40 Virus Exposure

The SV40 virus has been proposed by some as an etiologic agent in some mesotheliomas. Although this proposal remains controversial, it is clear that the presence or absence of exposure to SV40 virus is not a criterion in confirming or excluding the diagnosis of mesothelioma.12

|

PITFALLS IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF MM |

The first “port of call” for the histologic diagnosis of MM is the hematoxylin-eosin stain. Immunohistochemical panels are adjuncts to diagnosis and should not be performed automatically or blindly without considering several factors. As stated previously the major determinants of which panel to use are (1) the location of the tumor— it will vary as to whether it is pleural, peritoneal, or another serosal surface; (2) the phenotypic problem—benign versus malignant, epithelioid, spindle, biphasic, small cell, or pleomorphic; and (3) the experience of the laboratory. A laboratory using immunohistochemical stains should perform them frequently, have well-established protocols, and should have an appreciation of their sensitivities and specificities with respect to the various morphologic problems. There is no single utopian immunohistochemical panel to cover all diagnostic “mesothelial” problems.

One of the problems in comparing the results of particular antibodies from different studies is a lack of standardization of immunohistochemical procedures. This can result in conflicting results for sensitivity and specificity for various antibodies. The study of King et al3 tabulates the data for antibody clone, manufacturer, dilution, and antigen retrieval methods for 5 antibodies used in separating benign and malignant mesothelial proliferations in 13 studies. It illustrates the wide variability used between the various studies. Prior to using an antibody for diagnosis a laboratory should have carried out an extensive workup to find the ideal conditions for routine use.

The type of pathologic sample may affect results. For example, tiny needle biopsies may show crush artifact and false-positive immunostaining with various antibodies. Also the edges of biopsies may show artifactual positive immunostaining. There may also be variation in interpretation of what is positive illustrated by the fact that some laboratories will only consider calretinin to be positive when there is nuclear staining, whereas a minority will consider cytoplasmic staining to be positive. This can significantly affect sensitivity and specificity.

Another problem associated with immunohistochemistry may be putting too much emphasis on focal immunopositivity. We would suggest that weak or focal staining of less than 10% of the cells should be considered as being negative when interpreting a panel of stains. Also one can observe positive immunostaining with mesothelial markers in reactive proliferations of submesothelial fibroblasts in the vicinity of nonmesothelial tumors and inflammatory pleural diseases—it is important not to diagnose these as mesotheliomas. In contrast, mesotheliomas may invade the underlying lung and entrapped epithelial cells may show positive immunostaining with epithelial markers. Careful correlation with the hematoxylin-eosin sections is necessary to avoid misinterpretation.

|

MESOTHELIOMA REVIEW PANELS |

Pathology review panels for putative mesothelioma cases have been functioning since the 1960s. These panels have served as a referral source for pathologists facing diagnostic problems and, more recently, to confirm diagnoses for large oncology treatment trials. The diagnosis of mesothelioma has been considered to be difficult although the increasing frequency of this malignancy and application of immunohistochemical staining has made the diagnosis more reliable. In a 1991 report from the US and Canadian Mesothelioma Panel, only 70.5% of 200 cases had a three-fourths majority of the panel. It should be emphasized that these represented referral cases and by their nature were already difficult. In a more recent report from the same panel, agreement among panel members as to benign versus malignant was 78% for a group of 217 cases.

|

SUMMARY |

This article gives broad guidelines for making the diagnosis of MM, which, although a rare tumor, has a grave prognosis and invariably has medicolegal implications. The salient recommendations are (1) histologic features and immunohistochemical panel are used in distinguishing benign from malignant mesothelial proliferations; (2) there is limited usefulness of cytology, histochemical stains, electron microscopy, and molecular markers; panels of antibodies are given, which need to be used according to the differential diagnosis in each case; (3) and in the typical case in which all features are concordant, 2 mesothelioma markers and 2 carcinoma markers may be adequate to make a diagnosis; however, when there are discordant findings, additional markers should be performed. The pathologist should always take the clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features into consideration and get expert second opinion in difficult cases, as necessary.

differentiated from clear cell renal cell carcinomas, clear cell carcinomas of the lung, clear cell melanoma, and other clear cell tumors that can metastasie to the pleur

Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009 Aug;133(8):1317-31.

Guidelines for pathologic diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma: a consensus statement from the International Mesothelioma Interest Group.

Husain AN, Colby TV, Ordóñez NG, Krausz T, Borczuk A, Cagle PT, Chirieac LR, Churg A, Galateau-Salle F, Gibbs AR, Gown AM, Hammar SP, Litzky LA, Roggli VL, Travis WD, Wick MR.

Department of Pathology, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60631, USA. ahusain@bsd.uchicago.edu

Abstract

CONTEXT: Malignant mesothelioma (MM) is an uncommon tumor that can be difficult to diagnose. OBJECTIVE: To develop practical guidelines for the pathologic diagnosis of MM. DATA SOURCES: A pathology panel was convened at the International Mesothelioma Interest Group biennial meeting (October 2006). Pathologists with an interest in the field also contributed after the meeting. CONCLUSIONS: There was consensus opinion regarding (1) distinguishing benign from malignant mesothelial proliferations (both epithelioid and spindle cell lesions), (2) cytologic diagnosis of MM, (3) key histologic features of pleural and peritoneal MM, (4) use of histochemical and immunohistochemical stains in the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of MM, (5) differentiating epithelioid MM from various carcinomas (lung, breast, ovarian, and colonic adenocarcinomas and squamous cell and renal cell carcinomas), (6) diagnosis of sarcomatoid mesothelioma, (7) use of molecular markers in the differential diagnosis of MM, (8) electron microscopy in the diagnosis of MM, and (9) some caveats and pitfalls in the diagnosis of MM. Immunohistochemical panels are integral to the diagnosis of MM, but the exact makeup of panels used is dependent on the differential diagnosis and on the antibodies available in a given laboratory. Immunohistochemical panels should contain both positive and negative markers. The International Mesothelioma Interest Group recommends that markers have either sensitivity or specificity greater than 80% for the lesions in question. Interpretation of positivity generally should take into account the localization of the stain (eg, nuclear versus cytoplasmic) and the percentage of cells staining (>10% is suggested for cytoplasmic membranous markers). These guidelines are meant to be a practical reference for the pathologist.

PMID: 19653732 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

Cancer Cytopathol. 2010 Apr 25;118(2):90-6.

The use of immunohistochemistry to distinguish reactive mesothelial cells from malignant mesothelioma in cytologic effusions.

Hasteh F, Lin GY, Weidner N, Michael CW.

Department of Pathology, University of California-San Diego Medical Center, 200 W. Arbor Drive, La Jolla, CA 92103, USA. fhasteh@ucsd.edu

Abstract

BACKGROUND: The distinction of benign from malignant mesothelial proliferations in cytologic specimens can be problematic. In this study, the authors investigated the utility of immunohistochemical (IHC) markers in making this distinction. METHODS: Archival paraffin-embedded cell blocks of pleural and peritoneal fluids from 52 patients with malignant mesothelioma (MM) and 64 patients with reactive mesothelial hyperplasia (MH) were retrieved. IHC stains included desmin, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), glucose-transport protein 1 (GLUT-1), Ki67, and p53. RESULTS: Desmin was positive in 84% (54 of 64) cases of reactive MH and in 6% (3 of 52) of MM cases (P < .001). EMA was positive in 9% (6 of 64) of benign and 100% (52 of 52) of malignant cases (P < .001). GLUT-1 was positive in 12% (5 of 43) of benign and 47% (7 of 15) of malignant cases. Ki67 showed strong nuclear positivity in >40% of mesothelial cells in 9% (6 of 64) of benign and 16% (8 of 49) of malignant cases (P = .38). p53 showed strong nuclear positivity in 2% (1 of 46) of benign and 47% (7 of 15) of malignant cases (P < .001). EMA positivity and desmin negativity were found in 2% (1 of 64) of reactive MH cases and 98% (49 of 52) of MM cases (P < .001). EMA negativity and desmin positivity were found in 86% (55 of 64) of reactive MH cases and 0% of MM cases. CONCLUSIONS: The combination of positive EMA and negative desmin strongly favors MM; conversely, a combination of negative EMA and positive desmin favors a reactive process. Likewise, strong membranous positivity for GLUT-1 and/or strong nuclear staining for p53 favors a mesothelioma. Ki67 proliferative index showed no significant difference between reactive MH and MM cases. (c) 2010 American Cancer Society.

PMID: 20209622 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

-

本帖最后由 于 2010-06-16 21:27:00 编辑

非常感谢Dr.djdnx 为我们提供最新的权威性参考文献。Dr.djdnx 的好学、敬业是我们学习的榜样。谢谢您!为了方便网友, 将上文中的图表上传,共参考。

在北美,胸膜间皮瘤与肺癌浸润胸膜腔的鉴别诊断很具挑战性,一旦诊断不当,就可能成为“Medical-legal cases"。因此,美国病理医生成立了间皮瘤专业组,制定有关间皮瘤诊断的指导意见。

上皮型恶性间皮瘤的形态学可以非常温和,具有“欺骗性”(Remarkable for their deceptive blandness)。因此,很容易被漏诊。

此病例是非常经典的例子。

- xljin8