| 图片: | |

|---|---|

| 名称: | |

| 描述: | |

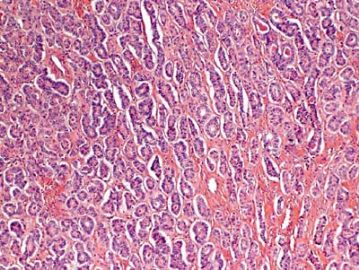

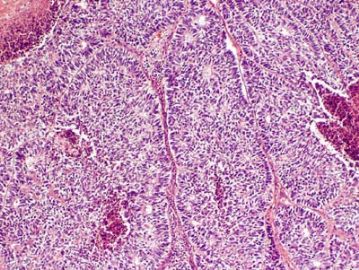

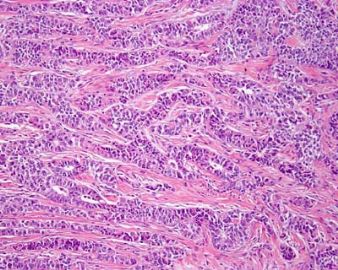

- 卵巢Sertoliform (or sex cord-like) variant of 子宫内膜样癌 (cqz-3)

-

本帖最后由 于 2009-09-08 07:15:00 编辑

-

Comparative analysis of alternative and traditional immunohistochemical markers for the distinction of ovarian sertoli cell tumor from endometrioid tumors and carcinoid tumor: A study of 160 cases.

Department of Gynecologic and Breast Pathology, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, DC, USA. chengquanzhao@yahoo.com

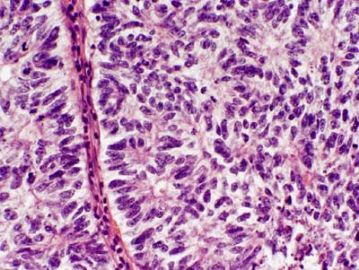

The main neoplasms in the differential diagnosis for primary ovarian tumors with a tubule-rich pattern are pure Sertoli cell tumor, endometrioid tumors (including borderline tumor, well-differentiated carcinoma, and the sertoliform variant of endometrioid carcinoma), and carcinoid tumor. Because traditional immunohistochemical markers [pan-cytokeratin (pan-CK), low molecular weight cytokeratin (CK8/18), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), inhibin, calretinin, CD99, chromogranin, and synaptophysin] can occasionally have diagnostic limitations, the goal of this study was to determine whether or not any alternative markers [cytokeratin 7 (CK7), estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), CD10, and CD56] have better diagnostic utility when compared with traditional markers for this differential diagnosis. Immunohistochemical stains for alternative, as well as traditional, markers were performed on the following primary ovarian tumors: pure Sertoli cell tumor (n = 40), endometrioid borderline tumor (n = 38), sertoliform endometrioid carcinoma (n = 13), well-differentiated endometrioid carcinoma (n = 27), and carcinoid tumor (n = 42). Extent and intensity of immunostaining were semiquantitatively scored. In addition, immunohistochemical composite scores (ICSs) in positive cases were calculated on the basis of the combination of extent and intensity scores. Cytokeratin 7 (CK7) was positive in 97% of endometrioid tumors, 13% of Sertoli cell tumors, and 24% of carcinoid tumors. The differences in the mean ICSs for endometrioid tumors versus Sertoli cell tumor or carcinoid tumor were statistically significant (P values ranging from <0.001 to 0.018). ER and PR were positive in 87% and 86% of endometrioid tumors, 8% and 13% of Sertoli cell tumors, and 2% each of carcinoid tumors, respectively. The differences in the mean ICSs for endometrioid tumors versus Sertoli cell tumor were statistically significant (P values ranging from <0.001 to 0.012). Among the epithelial markers, EMA seemed to be the most discriminatory but only slightly better than CK7, ER, or PR. Pan-CK and CK8/18 were not helpful. CD10 showed overlapping patterns of expression in all categories of tumors. Among the sex cord markers, CD10 was markedly less useful than inhibin or calretinin; CD99 was not discriminatory. CD56 showed overlapping patterns of expression in all categories of tumors. Among the neuroendocrine markers, CD56 was less useful than chromogranin or synaptophysin. When traditional immunohistochemical markers are problematic for the differential diagnosis of ovarian Sertoli cell tumor versus endometrioid tumors versus carcinoid tumor, adding CK7, ER, and/or PR to a panel of markers can be helpful. Endometrioid tumors more frequently express CK7, ER, and PR and show a greater extent of immunostaining in contrast to Sertoli cell tumor and carcinoid tumor. Compared with traditional epithelial markers, CK7, ER, and PR are nearly as advantageous as EMA. Inhibin is the most discriminatory sex cord marker, and CD10 is not helpful in the differential diagnosis. Chromogranin and synaptophysin are excellent discriminatory markers for carcinoid tumor, and CD56 is neither sufficiently sensitive nor specific enough for this differential diagnosis to warrant its use in routine practice.

Am J Surg Pathol. 2007 Feb;31(2):255-66.![]()

-

Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008 Oct;27(4):507-14.

-

SF-1 is a diagnostically useful immunohistochemical marker and comparable to other sex cord-stromal tumor markers for the differential diagnosis of ovarian sertoli cell tumor.

Department of Pathology, Magee-Womens Hospital, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213, USA. zhaoc@upmc.edu

Immunohistochemistry can be an important part of the diagnosis of Sertoli cell tumor of the ovary, including distinction from non-sex cord-stromal tumors such as the sertoliform variant of endometrioid carcinoma and carcinoid. Several good markers for this differential diagnosis have been identified, particularly inhibin, Wilms tumor 1 gene product (WT1), epithelial membrane antigen, and chromogranin; however, many available markers have limitations to some degree. Steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1; adrenal 4-binding protein; Ad4BP) is a nuclear transcription factor involved in gonadal and adrenal development. In the testes, SF-1 is expressed in Sertoli cells. Immunohistochemical expression of this marker in ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors, including utility for differential diagnosis, has not been rigorously evaluated. As an extension of our previous immunohistochemical studies of ovarian Sertoli cell tumor, expression of SF-1 and comparison with WT1 and inhibin were assessed in 111 primary ovarian tumors: 27 Sertoli cell tumors, 60 endometrioid tumors (including borderline tumors, conventional well-differentiated carcinomas, and sertoliform variants of carcinoma), and 24 carcinoids. SF-1 was expressed in 100% of Sertoli cell tumors but not in endometrioid tumors or carcinoid. WT1 was expressed in 100% of Sertoli cell tumors and 17% of endometrioid tumors; all carcinoids were negative. Inhibin was expressed in 96% of Sertoli cell tumors and 2% of endometrioid tumors (4% of conventional well-differentiated carcinomas); all carcinoids were negative. The extent of expression of all 3 markers was similar in Sertoli cell tumor but greatest for WT1: 63%, 96%, and 78% of cases showed expression of SF-1, WT1, and inhibin, respectively, in more than 50% of tumor cells. Immunohistochemical composite scores combining both extent and intensity of staining in positive cases were calculated for Sertoli cell tumor (possible range: 1-12). Combined extent/intensity of immunostaining was similar for all 3 markers, but WT1 showed the most robust immunoreactivity in positive cases (mean immunohistochemical composite scores for SF-1, WT1, and inhibin: 6.1, 10.8, and 7.8, respectively). We conclude that for the differential diagnosis with endometrioid tumors and carcinoid of the ovary, SF-1 is a sensitive and specific immunohistochemical marker for Sertoli cell tumor and that SF-1 is diagnostically comparable with other good sex cord-stromal markers.

-

APMIS. 2008 Sep;116(9):842-5.

-

Primary sex cord-like variant of endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis.

Department of Pathology, Länsi-Pohja Central Hospital, Kemi, Finland.

Endometriosis, a relatively common disease generally affecting women in the reproductive age group, is mostly found in the pelvic organs. Although endometriosis is a benign disease, some malignant tumors have been reported to develop in endometriotic lesions, most commonly in the ovary. The relationship between endometriosis and malignancy is not well known, but the majority of endometriosis-associated ovarian malignancies are usually endometrioid adenocarcinomas and clear cell carcinomas. The sex cord-like variant of endometrioid adenocarcinoma is a rare tumor that histologically closely resembles the sex cord-stromal tumor. Despite its rarity, the correct histological diagnosis of the sex cord-like variant of endometrioid adenocarcinoma is crucial to avoid misdiagnosis of a less aggressive tumor. We here report a 53-year-old woman who was diagnosed as having this very rare subtype of endometroid adenocarcinoma curiously arising from an endometriotic lesion at the site of previous salpingo-oophorectomy. The tumor was diagnosed based on light microscopy and immunohistochemistry.

-

Semin Diagn Pathol. 2005 Feb;22(1):3-32.

-

Immunohistochemistry as a diagnostic aid in the evaluation of ovarian tumors.

Department of Pathology, Royal Group of Hospitals Trust, Belfast, Northern Ireland. glenn.mccluggage@bll.n-i.nhs.uk

Aspects of immunohistochemistry (IHC), which are useful in the diagnosis of ovarian tumors (mostly neoplasms but also a few tumor-like lesions), are discussed. The topic is first approached by considering the different growth patterns and cell types that may be encountered. Then a few other specific situations in which IHC may assist are reviewed. Selected findings largely, or only, of academic interest are also mentioned. One of the most common situations in which IHC may aid is in the evaluation of tumors with follicles or other patterns which bring a sex cord-stromal tumor into the differential. The distinction between a sex cord tumor and an endometrioid carcinoma with sex-cord-like patterns may be greatly aided by the triad of epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), inhibin, and calretinin, the latter two being typically positive and EMA negative in sex cord tumors, the converse being typical of endometrioid carcinoma. It should be emphasized that granulosa cell tumors may be inhibin negative and, albeit less specific, calretinin is more reliable in evaluating this particular issue. Lack of staining for inhibin and calretinin may also be supportive in leading to consideration of diverse other neoplasms that may form follicles, including metastatic tumors as varied as carcinoid and melanoma. The well-known staining of the latter neoplasm for S-100 protein and HMB-45 may be very helpful in evaluating melanomas with follicular or other unusual patterns, a challenging aspect of ovarian tumor interpretation. The most common monodermal teratoma, struma ovarii, usually has an overt follicular pattern and is easily recognized, but recognition of unusual appearances ranging from oxyphilic to clear cell to various patterns of malignant struma may be greatly aided by a thyroglobulin or TTF 1 stain. IHC for neuroendocrine markers may assist in the diagnosis of primary and metastatic carcinoid tumor. The broad differential diagnosis of glandular neoplasms with an endometrioid-pseudoendometrioid morphology, or mucinous cell type, has been the subject of much exploration in recent years, particularly the distinction between primary and metastatic neoplasms. The well-known CK7 positive, CK20 negative phenotype of primary endometrioid carcinoma, and the converse profile in most metastatic large intestinal adenocarcinomas with a pseudoendometrioid morphology, has been much publicized but albeit an appropriate supportive adjunct in many cases, exceptions from the typical staining pattern may be encountered. It is even less helpful in the case of primary versus metastatic mucinous neoplasia. Evaluation of the expression of mucin gene products has shown mixed, essentially unreliable, results. Experience with other new markers, such as CDX-2, villin, beta catenin, and P504S (racemase), is limited but is in aggregate promising with regard to providing some aid in this area. The rare differential of metastatic cervical adenocarcinoma versus primary ovarian mucinous or endometrioid carcinoma may be aided by strong p16 staining of the former. Staining for alpha-fetoprotein may aid in confirming the diagnosis of endometrioid-like (and hepatoid) variants of yolk sac tumor. Ependymoma of the ovary may also have an endometrioid-like glandular pattern, but positive stains for glial fibrillary acidic protein contrast with the negative results in others neoplasms with a similar pattern. Immunostains may be very helpful in the evaluation of oxyphilic tumors and tumor-like lesions and in some unusual forms of clear cell neoplasia, such as clear cell struma, both subjects being reviewed herein. Immunostains may highlight both the presence and extent of epithelial cells in a variety of circumstances, including microinvasive foci in cases of serous borderline tumors and mucinous carcinomas, and in determining the extent of carcinoma cells and reactive cells within mural nodules of mucinous neoplasms. As in tumor pathology in general, various markers may be crucial in the diagnosis of small round cell tumors of the ovary, and familiar markers of epithelial, lymphoid, leukemic, and melanocytic neoplasms may assist in the analysis of high grade tumors with a poorly differentiated carcinoma, lymphoma-granulocytic sarcoma, malignant melanoma differential. The evaluation of ovarian cystic lesions may be aided by thyroglobulin or TTF 1 (cystic struma), glial fibrillary acid protein (ependymal cysts), and inhibin-calretinin (follicle cysts and unilocular granulosa cell tumors). Stains for trophoblast markers may occasionally aid in the evaluation of germ cell tumors, although routine stains should usually suffice; they may be of academic interest in confirming trophoblastic differentiation in some high grade surface epithelial carcinomas.