| 图片: | |

|---|---|

| 名称: | |

| 描述: | |

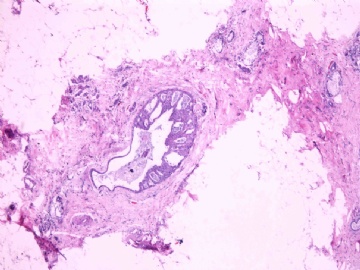

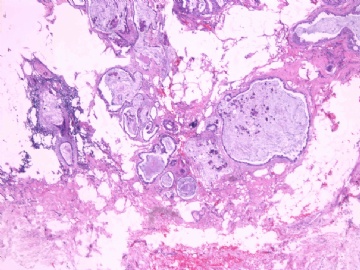

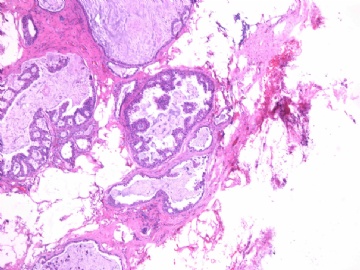

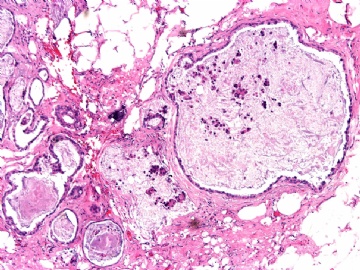

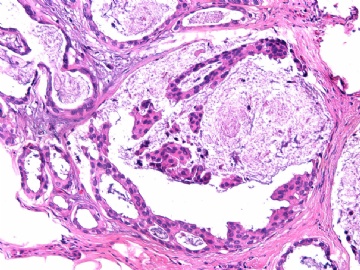

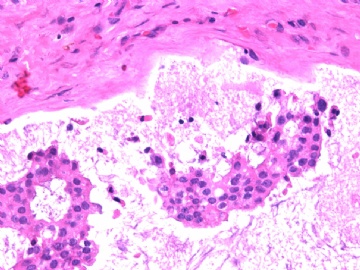

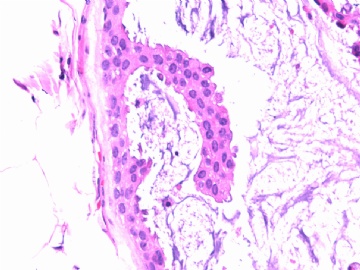

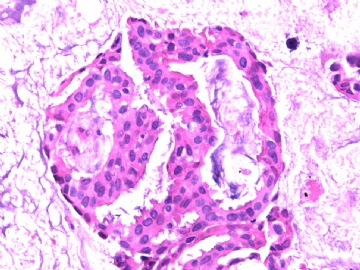

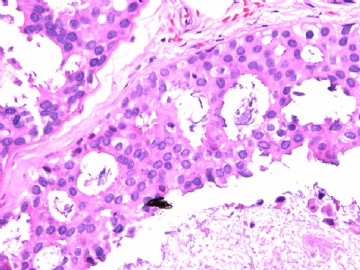

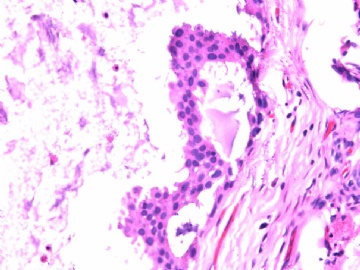

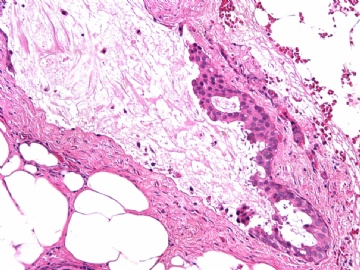

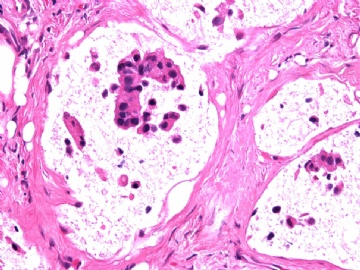

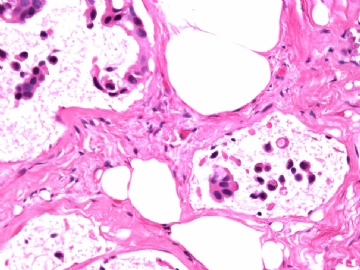

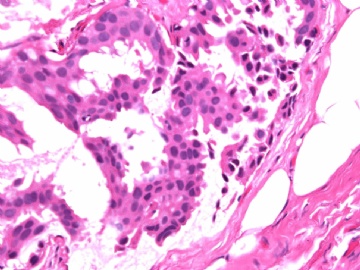

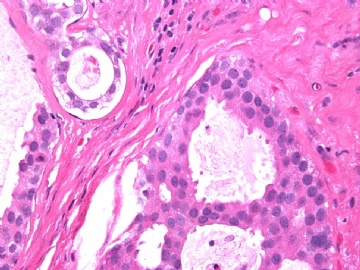

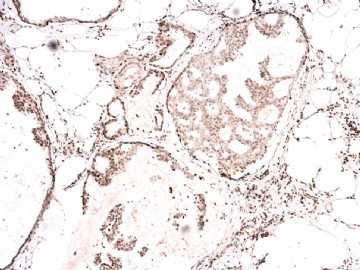

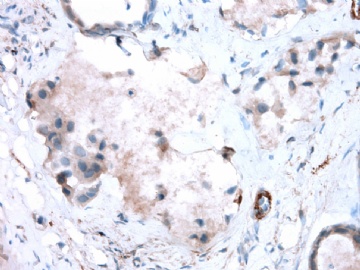

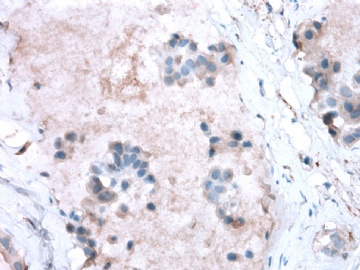

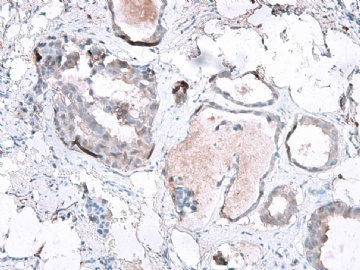

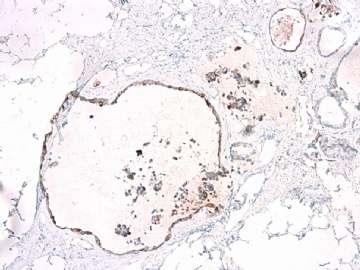

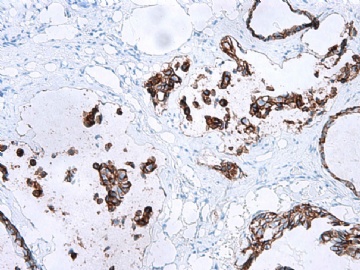

- B2865女性/62岁。 右乳腺肿块 0.8cm, 诊断?(IHC10-8-28)

Histopathology. 2008 Nov;53(5):545-53.

Gadre SA, Perkins GH, Sahin AA, Sneige N, Deavers MT, Middleton LP.

Department of Pathology, The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Abstract

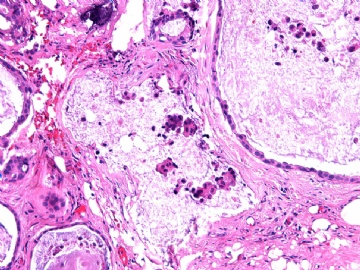

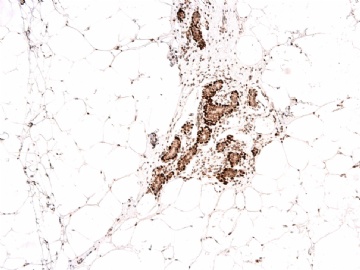

AIMS: Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) associated with invasive mucinous carcinoma (IMC) has not been well characterized. The aim was to characterize mucinous DCIS (mDCIS) of the breast and to describe, to our knowledge for the first time, neovascularization in mucin.

METHODS AND RESULTS: The pathology reports and slides were reviewed from 44 patients treated between 2003 and 2006 at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, whose diagnosis fulfilled the criteria of IMC or DCIS with mucin production. The patients, all female, had a mean age of 62 years. DCIS was present in 93% of cases and the predominant histological types were solid, cribriform and micropapillary. The DCIS was grade 1 in 12 of 41 cases (29.3%), grade 2 in 25 of 41 cases (61%) and grade 3 in four of 41 cases (9.8%). Mucin was seen in the lumen of the ducts involved by DCIS in 88% of cases, mucin and vessels in 63.4% of cases and neither mucin nor vessels in 12.2%. The DCIS was vascular endothelial growth factor-positive, platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta-positive and CDX-2-negative (100%). Occasional luminal cells within the DCIS were immunopositive for CD68.

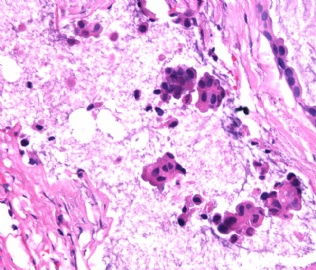

CONCLUSIONS: A significant number of mDCIS showed neovascularization in intraluminal mucin. When identified on core needle biopsy, the presence of vascularized mucin should not be used alone to discriminate between invasive and in situ carcinoma. A hypothesis proposed for the source of recruitment of vessels in the mucin is that mucin can promote neovascularization and that tumour cells invade not into the adjacent fibroconnective tissue, but rather into the mucinous, richly vascularized stroma that they have induced. Alternatively, it is possible that both cells and their secretory product invade together. To our knowledge, this is the first study to characterize neovascularization within the mucinous component of DCIS associated with and without IMC.

- 王军臣

-

本帖最后由 于 2010-08-28 04:43:00 编辑

非常有趣的研究,但是有些费解。

研究对象:44例乳腺导管原位癌伴有导管内黏液(mDCIS)或DCIS伴有小灶浸润性黏液癌(IMC)。

研究结果:mDCIS癌细胞VEGF+、PDGFR-Beta+、CDX-2-;

结论:mDCIS能在导管内黏液中诱导新血管形成。(不知血管内皮如何来源?)。乳腺空心针穿刺活检中看到富有血管的黏液不能做为区分浸润性癌还是原位癌的依据。

假设:mDCIS黏液中新血管形成是由黏液促进的新生血管化,肿瘤细胞不是浸润导管外的纤维结褅组织,而是浸润由黏液诱导产生的导管内富于新生血管的黏液。我的理解也许有误,请指正。

上述文献是主要研究mDCIS中导管内黏液血管形成机制,未讲的如何鉴别10楼中请教的2个问题。请继续发表意见,谢谢!

- xljin8

-

本帖最后由 于 2010-08-28 12:41:00 编辑

| 以下是引用xljin8在2010-8-27 6:37:00的发言:

请教大家: 1)如何鉴别“黏液外溢”和黏液性癌时“癌细胞漂浮在黏液湖中”? 2)如果是DCIS,导管因机械因素造成破裂后,癌细胞进入间质,这种情况是否存在象浸润性癌一样的转移危险? |

1)有此一说:

黏液外溢时,肌上皮存在;如果没有ADH或DCIS,漂浮的上皮条索呈线状;如果有ADH或DCIS,其形态与周围ADH或DCIS相似。粘液癌时,漂浮的癌细胞团无肌上皮。当然这是纯理论,实际工作中即使染肌上皮也可能无法区分。

另一说:脱落的上皮保持周围管腔的轮廓。

2)无充分依据的推测:

原位癌进展为浸润性癌,在细胞遗传学上需要获得某种基因突变,能够突破基底膜、促血管、在原来的生长部位之外继续存活繁殖。机械作用造成的上皮移位(包括原位癌),其细胞没有上述突变,因此不能存活,会发生退变、死亡。因此无转移危险。

另一个推测依据:做细胞培养时,条件非常严格,普通细胞很难在另一种环境下存活、生长。

这两个问题非常期望有研究经验的老师解答,或者提供资料。

谢谢金老师!

华夏病理/粉蓝医疗

为基层医院病理科提供全面解决方案,

努力让人人享有便捷准确可靠的病理诊断服务。

-

本帖最后由 于 2010-08-28 05:29:00 编辑

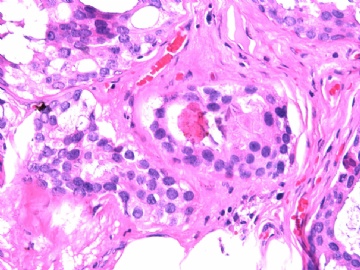

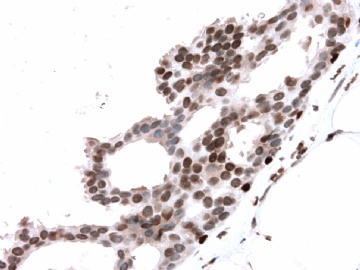

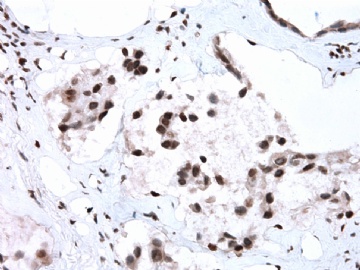

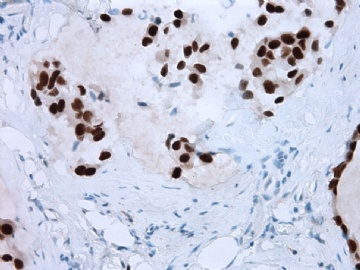

谢谢Dr.Abin上述分析,并看出此病例P63表达的特殊现象。

如何解释?好问题! 试作解答,不要见笑

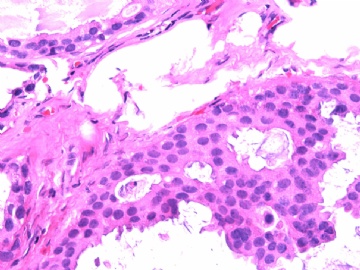

试作解答,不要见笑

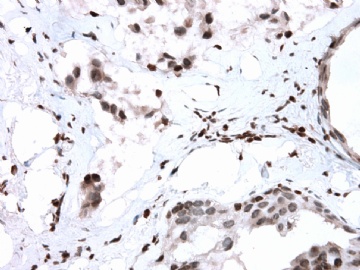

我们习惯用肌上皮的IHC标记来判断浸润癌与原位癌,实际上区别浸润与原位的严格标准是癌细胞是否突破基底膜。众所周知,基底膜的基本构成是Laminin和III型胶原,而不是肌上皮细胞。因此,肌上皮细胞消失不等于浸润性癌,如微腺体腺病时肌上皮细胞标记阴性,而Laminin和III型胶原阳性就是非常好的例子。这是要表述的第一层意思。

需要说明的第二点是肌上皮细胞对同一种IHC标记的不均一性,由肌上皮细胞分化程度的差异和/或功能状态的不同所导致。因此,一般要用二种以上的抗体标记去染色(推荐用P63 和SMMHC).

第三点是要注意P63异表达,少数癌细胞(浸润或原位)可表达肌上皮标记。

本病例IHC显示P63+可能就是这种情况。

望指教,谢谢!

- xljin8

All questions are very in details.

I thibk it is DCIS case.

如果是DCIS,导管因机械因素造成破裂后,癌细胞进入间质,这种情况是否存在象浸润性癌一样的转移危险. The risk will be different with true stromal invasion.

breast ductal epithelial cells (benign or malignant) can be positive for P63. I remember that some papers report it even though I cannot find the paper now.

-

本帖最后由 于 2010-09-01 23:21:00 编辑

Am J Surg Pathol. 2009 Feb;33(2):227-32.

Phenotypic alterations in ductal carcinoma in situ-associated myoepithelial cells: biologic and diagnostic implications.

Hilson JB, Schnitt SJ, Collins LC.

Department of Pathology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02215, USA.

Abstract

Recent molecular studies have indicated that ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)-associated myoepithelial cells (MECs) show differences from MECs in normal breast tissue. Such alterations may influence the progression of DCIS to invasive cancer. The purpose of this study was to investigate further phenotypic alterations in DCIS-associated MECs. Paraffin sections of 101 cases of DCIS (56 without and 45 with associated invasive carcinoma) were immunostained for 7 MEC markers: smooth muscle actin, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (SMMHC), calponin, p63, cytokeratin (CK) 5/6, CD10, and p75. In each case, the distribution and intensity of staining for each marker in DCIS-associated MECs was compared with that in MECs surrounding normal ductal-lobular structures on the same slide. In 85 cases (84.2%), DCIS-associated MECs showed decreased expression of one or more MEC markers when compared with normal MECs. The proportion of cases that showed reduced expression was 76.5% for SMMHC, 34.0% for CD10, 30.2% for CK5/6, 17.4% for calponin, 12.6% for p63, 4.2% for p75, and 1% for smooth muscle actin. Reduced MEC expression of SMMHC was significantly more frequent in high grade than in non-high-grade DCIS (84.8% vs. 61.5% of cases, P=0.01). We conclude that DCIS-associated MECs show immunophenotypic differences from MECs surrounding normal mammary ductal-lobular structures. The biologic significance of this remains to be determined. However, these results indicate that the sensitivity of some MEC markers is lower in DCIS-associated MECs than in normal MECs. This observation should be taken into consideration when selecting MEC markers to help distinguish in situ from invasive breast carcinomas.