| 图片: | |

|---|---|

| 名称: | |

| 描述: | |

- 35岁女性,卵巢肿物,是恶性吗?

-

本帖最后由 于 2010-01-03 10:15:00 编辑

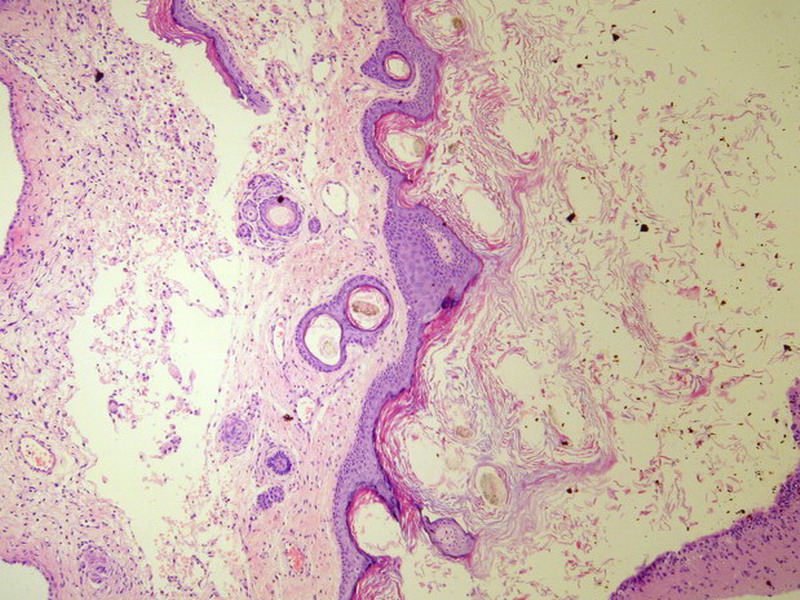

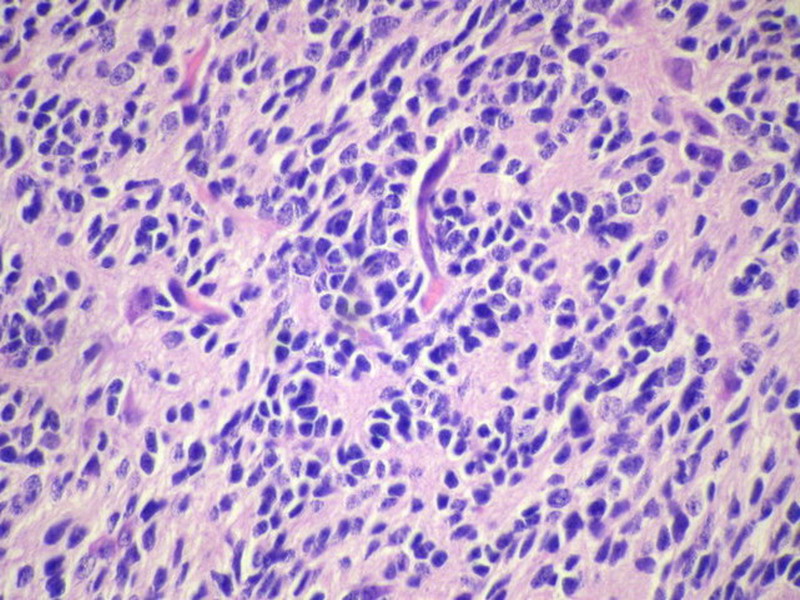

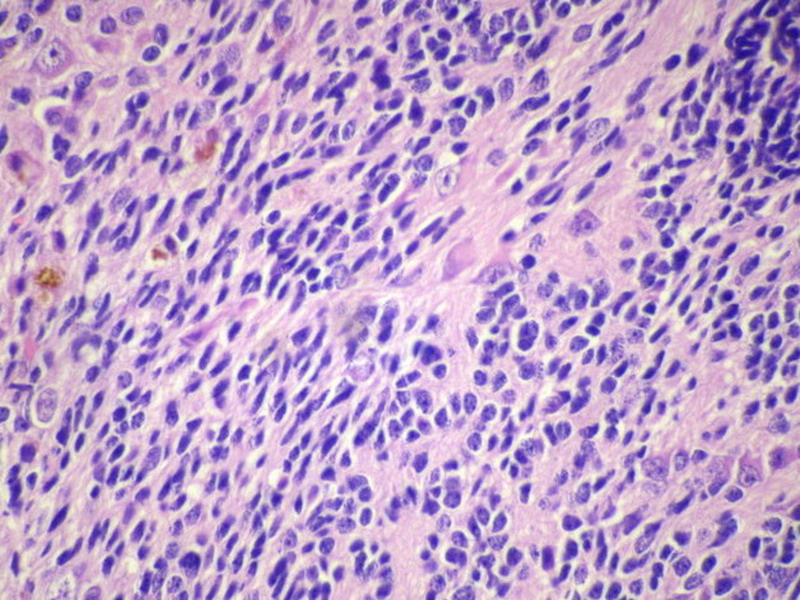

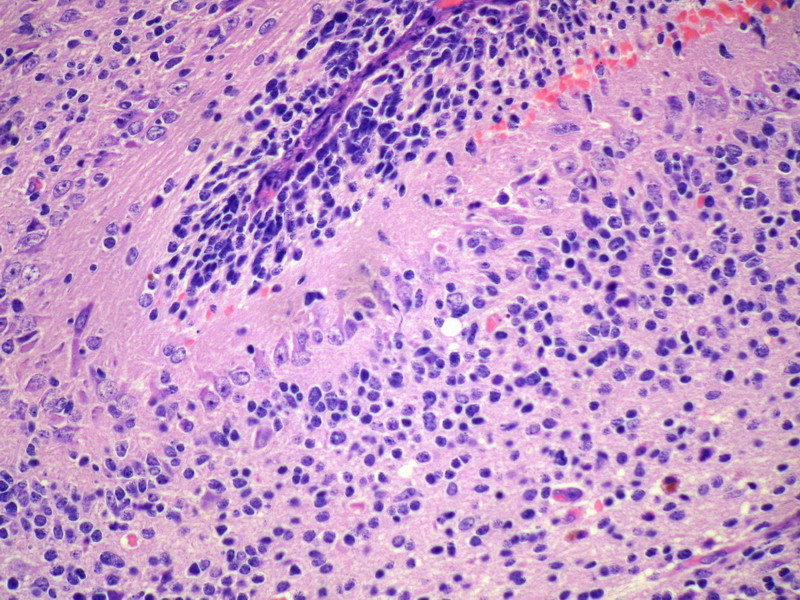

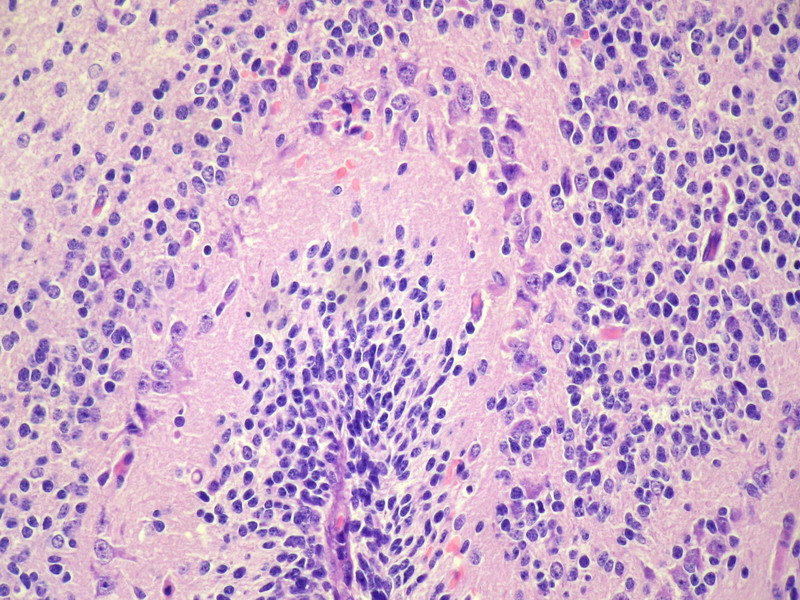

The excellent quality of photos has made interpretation of this case less difficult than necessary. This is a case of immature teratoma of ovary in a 35-year-old woman, which is different from a benign mature cystic teratoma (dermoid cyst) of ovary in containing immature/primitive neuroepithelial elements in addition to mature or differentiated elements of two or more different lineages of embryonal development (ectoderm, endoderm and mesoderm). I am surprised that only one post has inquired about the size and gross appearance (ratio of cystic to solid areas; if cystic, what is the appearance of cystic contents [is there any hair admixed with thick, greasy, yellow or gray paste, or any tooth-like protuberance on cystic wall]; and whether there was any defect/rupture of the ovarian surface) of the specimen. This information helps pathologic assessment greatly and, though could be deducted in this case by experience, could have helped some discussants avoid confusion.

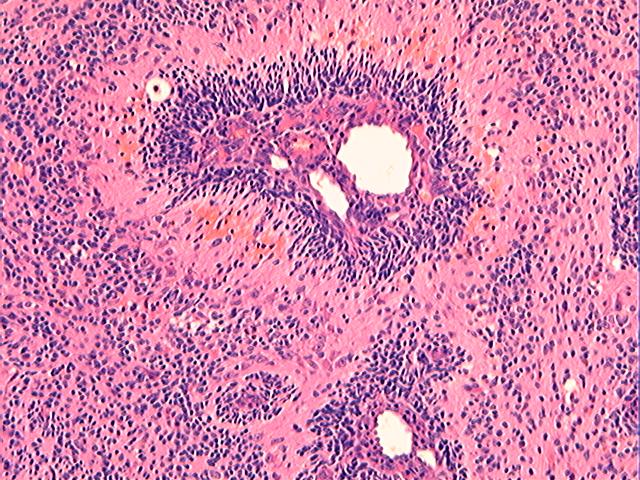

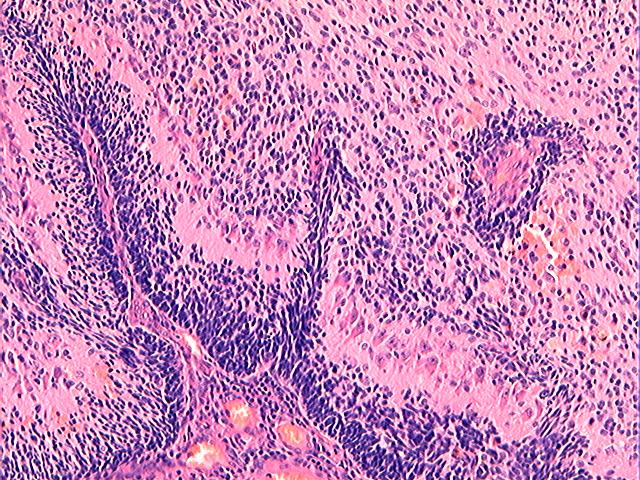

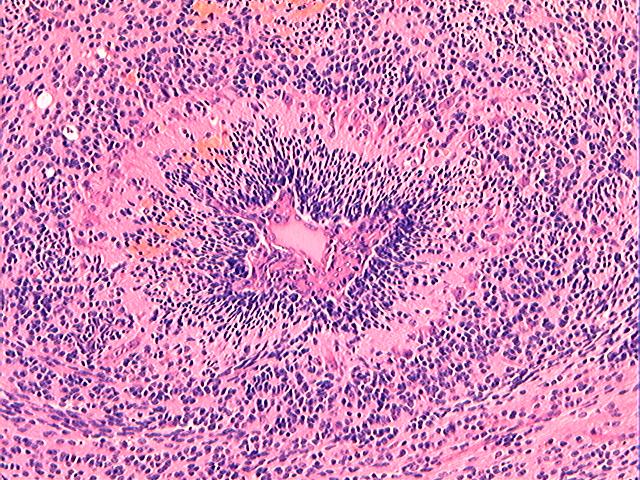

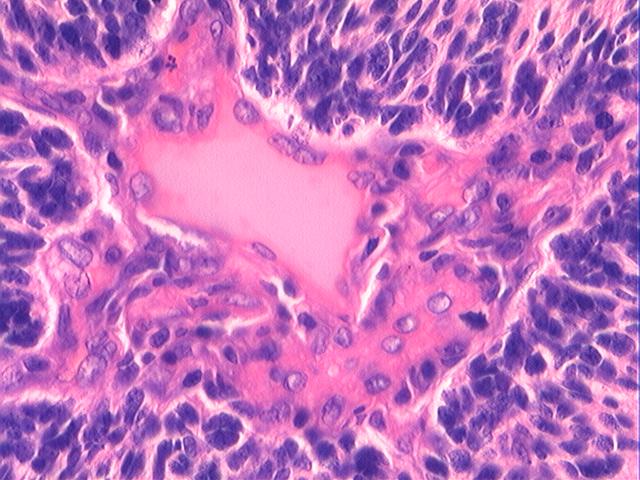

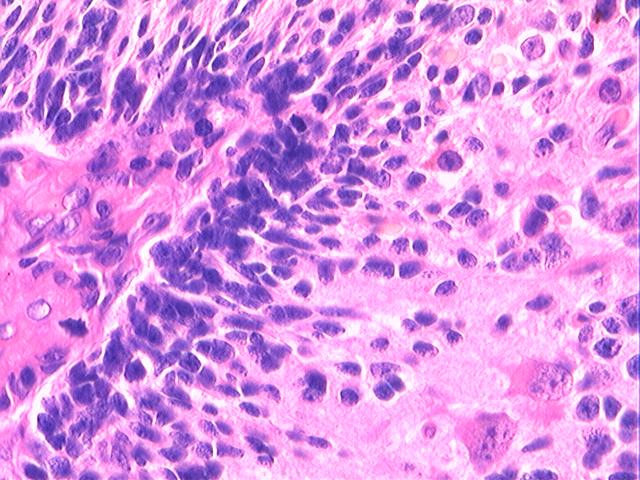

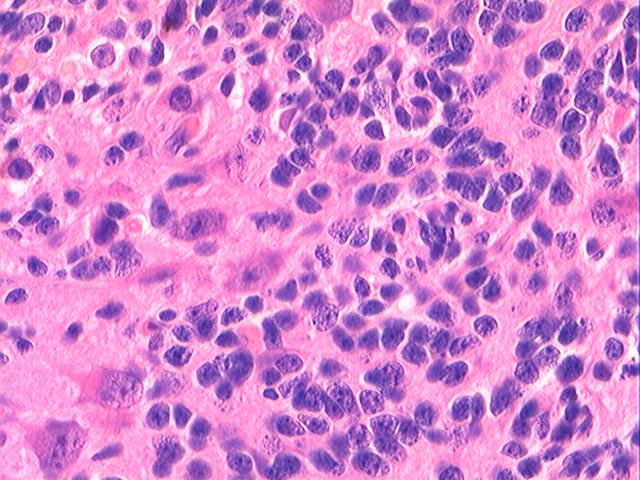

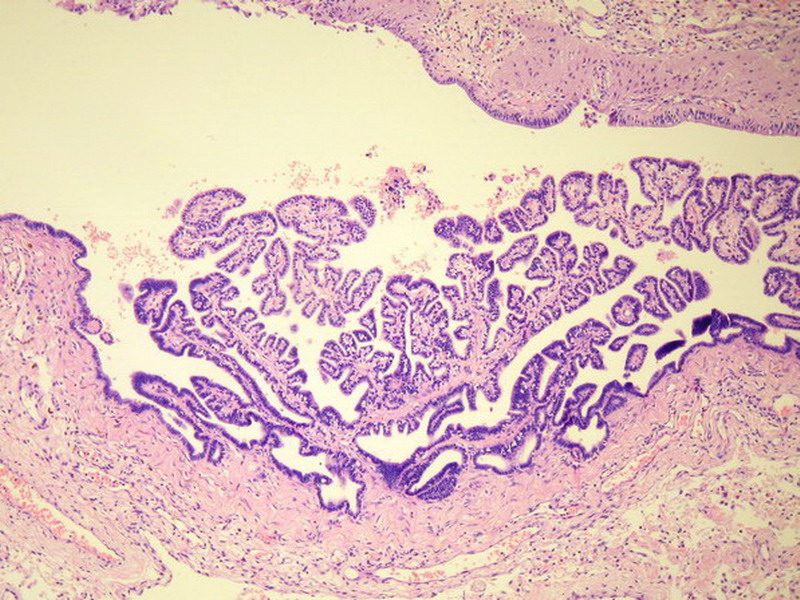

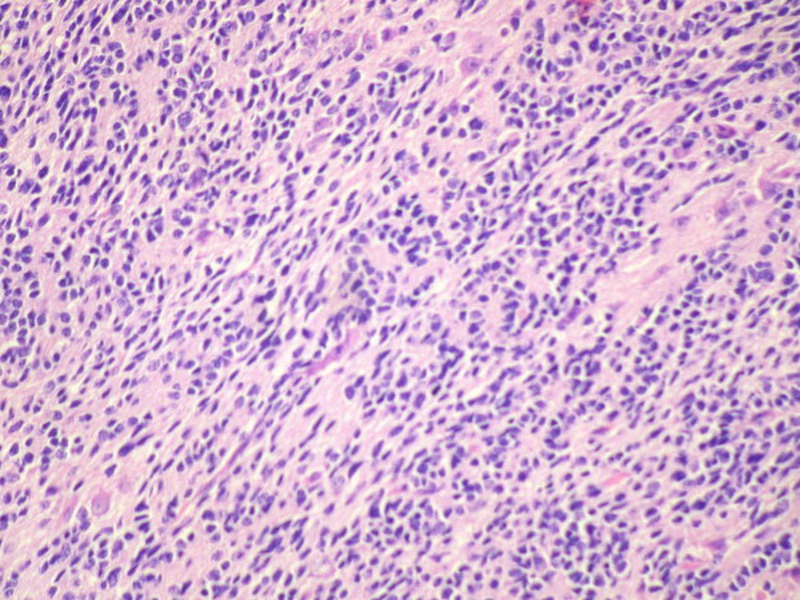

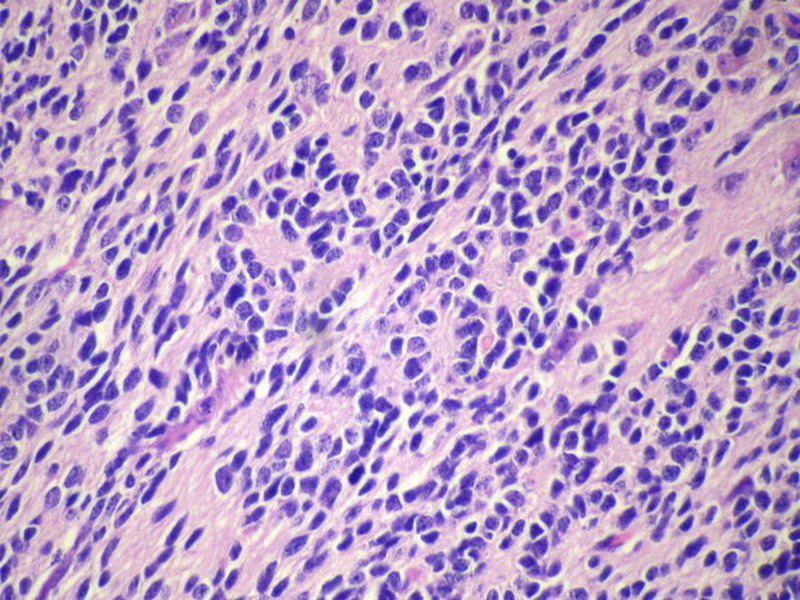

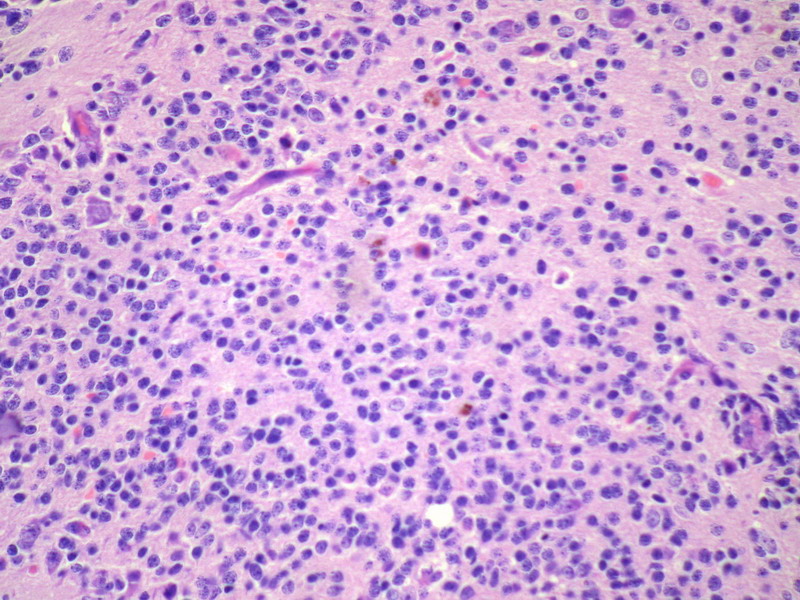

Three batches of photos have been uploaded. Low power views (Figures 1-2 of the second batch) clearly show both mature (light pink, hypocellular and a majority of area) and less mature (dark blue and hypercellular areas) neural tissue. These views are important in the grading of this lesion. The first batch of six photos (and figures 3-7 and 11 of the second batch and figures 7-9 of the third batch) clearly shows immature but very organized cerebellar cortex with leptomeninges overlying a subpial layer of external granular layer, a hypocellular molecular layer, a Purkinje cell layer, and an internal granular layer in such order. The architecture is abnormally developed so that these layers are not horizontal as would be found in the cerebellum of a normal third trimester fetus or an infant. The leptomeninges are enclosed in a small irregular space and surrounded by the subpial external granular layer, mimicking a perivascular pseudorosette. This is not indicative of ependymal differentiation. Although I have not seen it in photos of this case, true ependymal differentiation in ovarian teratoma is frequently seen as formation of small, round to oval ependymal canals by multilayered primitive cells (identical to that seen in an ependymoblastoma and an embryonal neural tube) or, less often, single layer of cuboidal or columnar ependymal epithelia. Figures 8-10 of the second batch and figures 3-6 of the third batch are without organoid architecture, but are certainly indicative of neural differentiation based on scattered large neurons present.

Pathologists are often confused about the definition of “immature/primitive” neuroepithelial elements in ovarian (and any other organ) teratomas. The main reason for this phenomenon is that mature neural tissue is almost always found in ovarian teratomas and consists of hypo- and hypercellular areas that merge imperceptibly into each other without sharp demarcation. This is complicated by the fact that some types of mature neural tissue are inherently hypercellular and consisting of small cells with little cytoplasm, while individual large differentiated neurons can be found in immature areas (as in this case). In general, basic histologic and cytologic details are again applicable here to help one identify truly immature (blast-like) cells - cellular density (degree of nuclear overlapping), variability of nuclear size and shape, chromatin pattern, and the density of mitotic figures (figure 5 of the first batch contains one) are very helpful in assessing the degree of maturation of these neural elements. In my opinion, this case clearly shows immature/primitive neuroepithelial elements.

Ovarian teratomas are very common neoplasms that fascinate pathologists because of their potential of diverse tissue differentiation recapitulating human embryonal development, the difficulty in grading them consistently, and their ability to develop differentiated neoplasms (benign and malignant alike) in rare cases. Immature ovarian teratomas are known to have the potential to spread to the peritoneum (such as gliomatosis peritonei), pelvic/periaortic lymph nodes, and even to other organs (e.g., lung) either months or years after surgical excision or, less commonly, at the time of initial surgery. The risk for metastasis and local recurrence has been correlated with the amount of immature or primitive neuroepithelial elements in the ovarian neoplasm by some experts, leading to various proposed grading systems for immature ovarian teratomas (the best known is by Norris et al). However, these grading systems are arbitrary (and hence, subjective) with criteria not clearly defined (not very reproducible between different pathologists) and have often been criticized as lacking practical predictive value in individual cases. Nonetheless, extensive sampling of ovarian teratomas for microscopic assessment of amount of immature neuroepithelial elements is important. I do not believe this case has enough immature elements to be graded as grade 3 according to the revised Norris criteria. The metastatic deposits of immature ovarian teratomas often appear incongruous with their clinical implication and consist of well differentiated tissue without any immature elements or frank cytologic malignancy, not unlike the much more notorious and malignant behavior of testicular teratomas (mature or immature) in men and children. For this reason, it is considered malignant, but different from typical malignant germ cell tumors (such as seminoma, embryonal carcinoma, yolk sac tumor, and choriocarcinoma) in behavior and response to nonsurgical oncotherapy. Not unexpectedly when present the metastatic disease is not very responsive to chemotherapy or irradiation, and the role of post-surgical chemotherapy after gross total resection of non-ruptured stage I ovarian immature teratoma is controversial.

The literature is full of case reports of the a situation where specific neoplasm arises in an ovarian teratoma, the better known examples of which include papillary thyroid carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, malignant melanoma, ependymoma, oligodendroglioma, astrocytoma, meningioma, choroid plexus papilloma (figure 2 in the third batch of photos is a small choroid plexus in this lesion) and pituitary adenoma (some even being hormonally functional). I do not believe any such second neoplasm exists in this case based on the available photos.

聞道有先後,術業有專攻

| 以下是引用杨斌在2009-12-24 23:39:00的发言:

青青子矜 did wonderful translation job! This is the exact environment I like to see more and more here. Everybody tosses their opinions based on morphologic analysis. There is no authority, but just different opinion and interpretations, as long as you can provide some in depth analysis. The point is not who is right at the end, but the differential diagnoses and how do you convince yourself and others to reach a logic and correct diagnosis. Happy New Year to you all! |

多谢杨老师对我们的鼓励!

新年快乐!

| 以下是引用Liu_Aijun在2009-12-25 8:24:00的发言:

|

| 以下是引用海上明月在2009-12-25 1:21:00的发言:

不知道这个肿块到底有多大,不知道这个肿块是否肉眼观有囊性结构。从提供的图片放大看,不是经典的神经管结构。但是,这管状结构的周围的确可见发育成熟的神经元和神经胶质。感兴趣的是,管状结构中央有较厚的管壁,有上皮内衬。似正在发育的中央导水管或室管膜样结构。问题是,围绕管状结构周围的深染的小短梭形或类圆形小细胞是什么细胞,还有一些区域可见成片的实性细胞聚集似乎将要形成“管状结构”。有可能就是未成熟的神经组织。 这可能是一个特例,虽然见不到经典的神经管。但从迹象看,可能是一些相对幼稚或曰胎儿型的神经组织,有类似于神经管分化的意义。因此,这可能是一个未成熟性畸胎瘤。多取材看看,如果没有皮肤及附件、原肠分化等结构存在,那可能是一个只有神经分化的单形性未成熟畸胎瘤。 未成熟畸胎瘤和恶性畸胎瘤绝不是一个相同的概念。未成熟是指胚胎发育的分化过程未达到成熟状态,如神经管,处在早期神经发育与分化阶段。将其分离在体外条件培养基中培养,是可以向成熟方向分化的。未成熟成分在一定意义上讲,是早期胎儿型的;而恶性畸胎瘤,其中含有至少有一种成分发生恶性转化,就如同经典的某组织起源的恶性肿瘤在畸胎瘤中。 以上议论,如有不妥,请鉴谅。 |

- If you have great talents, industry will improve them; if you have but moderate abilities, industry will supply their deficiency. 如果你很有天赋,勤勉会使其更加完美;如果你能力一般,勤勉会补足其缺陷。