| 图片: | |

|---|---|

| 名称: | |

| 描述: | |

- 女,35岁 直肠息肉

-

zhenshijian 离线

- 帖子:1069

- 粉蓝豆:91

- 经验:1364

- 注册时间:2008-04-20

- 加关注 | 发消息

-

本帖最后由 TK1905 于 2012-06-16 11:31:59 编辑

楼主您的图片感觉比我找到的很多图片都经典!

除了这张:

Diagnosis:

Inflammatory "cap" polyp (炎症性帽状息肉)![]()

Discussion

Cap polyposis is an uncommon disease first described by Williams et al in 1985 and was proposed to represent a response to chronic mucosal prolapse . Since that time, fewer than 50 cases have been reported in the literature. Cap polyposis probably affects men and women with near equal frequency and variations in gender distributions among different studies likely reflect the small number of patients evaluated to date. This disorder may occur within any racial group, but is more commonly reported in eastern and southeastern Asia. It also occurs within a wide age range, affecting patients as young as 12 years of age, as well as older adults. At least 50% of patients do not have a history of chronic constipation or straining prior to the onset of cap polyposis. In one recent review of 11 patients, the male/female ratio was 9/2, with a mean age of 20 years (range: 15-54 years); 64% of patients had a history of chronic constipation. In that study, only two patients had documented abnormal anorectal function, including one with rectal intussusception and one with rectal prolapse . ![]()

Patients with cap polyposis commonly present with symptoms of mucoid diarrhea, which may be associated with protein wasting, rectal bleeding, or tenesmus. The rectum is involved in more than 80% of cases; however, the disease often affects the sigmoid colon and may even extend into the ascending colon in a retrograde, continuous fashion. Endoscopically, the polyps are usually sessile and vary from a few millimeters to several centimeters. As in the current case, the polyps may form confluent plaques on the mucosal surface. The lesions, which may be solitary or multiple, are often friable and erythematous with ulceration . ![]()

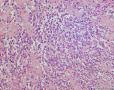

Cap polyps are characterized by several features. Most are composed of elongated, hyperplastic crypts lined by mucin-depleted epithelial cells that show regenerative changes, including nuclear enlargement and increased mitotic activity. The surface epithelium is often attenuated and may be ulcerated. As a result, there is usually an inflammatory "cap" of granulation tissue on the surface with adherent mucin, fibrin, inflammatory cells, and denuded epithelial cells. The lamina propria shows a variable amount of active inflammation, particularly in the superficial areas underlying erosions or ulcers. Although a small number of smooth muscle fibers may emanate from the muscularis mucosae in some cases, most cap polyps do not contain abundant smooth muscle fibers within the lamina propria. ![]()

The differential diagnosis includes a number of unrelated entities that share gross and/or histologic overlap with cap polyposis and encompasses forms of colitis to several polyposis syndromes.

Ulcerative Colitis

Based upon the gross appearance of the colon, ulcerative colitis with pseudopolyps is included in the differential diagnosis of cap polyposis [23]. However, the intervening mucosa is usually endoscopically normal in patients with cap polyposis, whereas patients with ulcerative colitis show erythema or other features of colitis in the non-polypoid mucosa. The histologic features of ulcerative colitis are also distinct from those of cap polyposis. For example, although pseudopolyps in chronic colitis may show features that closely resemble the normal colonic mucosa, or show chronic colitis with or without active disease, cap polyps show predominantly hyperplastic/regenerative changes with cystically dilated crypts or crypts with limited luminal serration, in a background of normal or near-normal lamina propria cellularity with minimal mononuclear cell inflammation, despite the presence of superficial ulceration. In addition, the intervening, non-polypoid mucosa may show mild crypt architectural distortion, but lacks mononuclear cell inflammation in the lamina propria. The presence of active inflammation with ulceration in a background mucosa that lacks chronic inflammation would be distinctly uncommon in patients with new-onset ulcerative colitis. ![]()

Mucosal Prolapse Syndrome

The inflammatory appearance of cap polyps may overlap morphologically with the type of lesions seen in mucosal prolapse or solitary rectal ulcer syndrome leading some investigators to propose that cap polyposis represents one of a spectrum of changes seen in mucosal prolapse [11, 18]. Both conditions show a predilection for the left colon, and, particularly, the rectum. However, the morphologic features of these two entities are sufficiently different to allow their distinction. For example, although cap polyps may be ulcerated with granulation tissue, they do not show other features typical of mucosal prolapse, such as ischemic-type injury or fibromuscularization of the lamina propria. The muscularis mucosae is histologically normal in most cap polyps, whereas it is usually thickened and associated with wisps of smooth muscle that extend into the lamina propria in mucosal prolapse. Cap polyposis has also been reported to involve the proximal colon, including the cecum, which are presumably unaffected by mucosal prolapse, particularly among asymptomatic patients [9, 21]. Although it is likely that cap polyposis and mucosal prolapse are both non-neoplastic, inflammatory processes, it is probable that these entities are unrelated. ![]()

Hamartomatous Polyposis

The polyps of cap polyposis may show morphologic features that raise the possibility of a hamartomatous polyposis syndrome, such as juvenile polyposis, Cowden's syndrome or Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Juvenile polyps show cystically dilated crypts within an inflamed stroma rich in eosinophils, often with surface ulceration and granulation tissue. The cystically dilated crypts of these polyps are evenly distributed throughout the polyp and the lesions may occur in extracolonic sites. In contrast, cystically dilated crypts in cap polyposis are more prominent toward the surface of the polyp, which also contains elongated crypts with luminal serration. Adherent mucin with inflammatory cells is also more commonly seen in cap polyps than in juvenile polyps. Polyps seen in Cowden's syndrome or Cronkhite-Canada syndrome may show features that, in isolation, mimic the features of cap polyposis, but they contain numerous mucus-filled cystically dilated crypts distributed throughout all areas of the polyp, more closely resembling juvenile polyps. Both of these disorders are also associated with extracolonic lesions involving the upper gastrointestinal tract as well as extraintestinal manifestations and dermatologic abnormalities. For instance, Cowden's disease is associated with breast cancer, thyroid disease, facial anomalies, renal cell carcinoma, lymhomas, papillomatosis of the lips and oropharynx, retinal gliomas, and skeletal changes as well as facial tricholemmomas, melanoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma [5, 25]. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome may produce clinical symptoms, such as protein wasting and diarrhea, similar to cap polyposis, but is also associated with skin hyperpigmentation, vitiligo, alopecia, onychodystrophy, glossitis, and cataracts [3, 6]. Knowledge of the clinical scenario usually allows distinction among these entities. ![]()

Cap polyposis may resolve spontaneously; however, most patients require some form of medical or surgical management [12, 16, 24]. Those with fewer than 10 polyps may be managed successfully with polypectomy alone in approximately 60% of cases. More extensive, symptomatic disease may be treated with a combination of stool softeners, anti-inflammatory agents (5-aminosalicylic acid, sulfasalazine, prednisolone) or antibiotics (metronidazole). Recently, some authors have reported endoscopic and histologic resolution of disease following infliximab therapy, suggesting a role for inflammatory mediators, such as TNF- a, in the progression of this disease [2, 13]. Rare patients with concomitant H. pylori gastritis have also been successfully managed with H. pylori eradication therapy [1, 15, 17]. Resection of the involved colon is usually reserved for patients who fail medical therapy. Recurrent symptomatic disease has been reported in up to 37% of cases following limited resection of the affected colon [22]. ![]()

The pathogenesis of cap polyposis is unknown. Its usual involvement of the rectum and/or sigmoid colon, clinical association with constipation and straining upon defecation, and histologic features have led investigators to suggest that these polyps are related to mucosal prolapse or intraluminal trauma [4, 8, 12, 18]. Most investigators believe that it represents a non-neoplastic inflammatory response to mucosal prolapse and consider it to be part of a spectrum of changes in mucosal prolapse syndrome. However, most patients with cap polyposis do not have a history of chronic constipation; larger series indicate that this disease usually occurs in patients in whom mucosal prolapse is infrequent, such as younger male patients without underlying colonic motility disorders [14]. Some reports have also described cap polyposis in association with diverticular disease, colorectal carcinoma, and colitis, suggesting that it may be a non-specific mucosal response to another underlying disorder [22, 26]. ![]()

The most intriguing hypotheses regarding the pathogenesis of cap polyposis implicate an infectious organism in the development of this disorder. Shimizu et al reported a case of cap polyposis in association with an E. coli colonic infection [22]. Although broad-spectrum antibiotics have proven ineffective in the treatment of most patients with cap polyposis, metronidazole is temporarily effective in ameliorating symptoms in some cases [8]. Several investigators have independently reported the successful resolution of cap polyposis in patients receiving H. pylori eradication therapy. Five such cases have been reported to date, all in patients who failed other forms of medical (steroids, metronidazole, bowel rest) or surgical therapy. In each case, the patient was found to have H. pylori-associated gastritis during the course of the illness, which was treated. All of the patients experienced a resolution of colonic symptoms after successful H. pylori eradication [1, 15, 17]. Based on these observations, the authors concluded that cap polyposis may represent an inflammatory response to an unidentified agent that shares an antibiotic sensitivity with H. pylori.

Discussion

Cap polyposis is a rare intestinal condition that was first described by Williams and associates in 1985 in a case series of 15 patients.1 These patients had distinctive inflammatory polyps without a significant family history or strong associations with other major colorectal diseases. From 1985 to 2004, 17 additional cases of cap polyposis were reported in the English language medical literature. Because of the rarity of this condition, these polyps are sometimes misdiagnosed as pseudopolyps in ulcerative colitis.2 In 2004, the second largest case series to date was published by Ng and colleagues, which included 11 cases of cap polyposis reported from 1993 to 2002.2 Our case study is the ninth reported case in the English language medical literature since 2003.

A review of the literature shows that cap polyposis tends to affect individuals of any age, at a median age of 52 years (range, 12–76 years).2 This finding is consistent with the average age of patients with cap polyposis reported over the past 7 years (52.8 years; range, 33–76 years).3–8 A case series conducted by Ng and coworkers showed that males are primarily affected by this condition; however, previous studies have found that females are affected more often than males (11%).2–8

Common symptoms of cap polyposis are mucous diarrhea, tenesmus, and rectal bleeding.9 Mucous diarrhea in these patients can be severe, resulting in excessive protein loss.2 A direct loss of protein from cap polyposis was confirmed in a 54-year-old woman via scintigraphy of technetium 99m-labeled diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid complexed to human serum albumin.10 There have also been reports of lower limb edema as a result of protein-losing enteropathy from cap polyposis. Likewise, approximately half of patients experience habitual straining during defecation and have chronic constipation.2

Endoscopically, cap polyps are small, red, sessile or semipedunculated, and range in size from several millimeters to 2 cm. The number of polyps varies from 1 to more than 100, and polyps are usually located at the apices of the mucosal folds, with normal intervening mucosa. The rectum and rectosigmoid colon are the most commonly affected sites, whereas the entire colon and stomach are rarely affected.2,10 Cap polyps are often covered with a thick layer of fibrinopurulent exudates. Performing a complete colonoscopy is important because cap polyposis has been reported to extend as far as the cecum. Polypectomy should be attempted for all polyps; however, it may not be possible to attain this goal if there are numerous polyps. In this scenario, adequate biopsies should be taken for histologic examination.2

Histologically, these polyps consist of elongated, distended, tortuous, and hyperplastic crypts that become attenuated toward the mucosal surface. The surfaces of these sessile polyps are ulcerated and covered by a thick layer of fibrinopurulent exudates, hence the term “cap polyps.” The lamina propria of the polyps also contains a large number of inflammatory cells.2

Morphologically, polyps associated with cap polyposis are distinct. Patients with cap polyposis are often misdiagnosed with ulcerative colitis or another inflammatory bowel disease (in 44.4% of cases over the past 8 years). Although inflammatory pseudopolyps in inflammatory bowel disease can have granulation tissue, the intervening mucosa has changes classically associated with inflammatory bowel disease. In contrast, the intervening mucosa is normal in cap polyposis. Due to the large numbers of polyps in these patients, a diagnosis of familial adenoma-tous polyposis is often considered; however, histologi-cally, the polyps in cap polyposis are not adenomatous. Finally, due to the variable presence of protein-losing enteropathy, Cronkhite-Canada syndrome can also be considered; however, the polyps in cap polyposis are not hamartomatous.

The exact etiology of inflammatory polyps in cap polyposis is still unknown.2 Buisine and associates found that the mucus in cap polyposis differs from that of the normal colon in terms of ultrastructural characteristics and com-position.11 However, the exact cause of protein loss has not been reported. In an attempt to investigate the presence of lymphatic channels in these polyps—which could lead to protein loss—a D2-40 stain was performed in this case, yielding negative results. Immunohistochemical stains proved the presence of vessels in the cap.

The exact cause of polyps with fibrinopurulent caps is also unknown; however, many researchers attribute these polyps to abnormal colonic motility and repeated trauma to the colonic mucosa caused by straining during defecation. Similar histologic features are present in conditions such as prolapsing mucosa, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, inflammatory cloacogenic polyps, and gastric antral vascular ectasia. Along with cap polyposis, these conditions comprise “mucosal prolapse syndrome” and are all caused by chronic straining at stool.2 In our case report, Figure 8 demonstrates the obliteration of the lamina propria by smooth muscle fibers.

The clinical course of cap polyposis has not yet been elucidated. This condition may, at times, have a self-limiting course, whether or not polypectomy is performed. However, complete polypectomy should be performed whenever possible, as it may be curative in some patients.2–6 Patients are advised to avoid straining during defecation if they have a history of difficult defecation or chronic constipation. Various medical treatments have been advocated, including metronidazole, immunosuppressive agents, and Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy.2 Numerous studies throughout the years have shown complete resolution of cap polyposis following therapy for H. pylori infection. Over the past 8 years, 4 of 9 (44.4%) cases were effectively treated with antibiotics commonly used for H. pylori infection.5,8 The role of met ronidazole in treating cap polyposis may be related to its anti-inflammatory effect rather than its antibiotic action; by acting as a radical scavenger, it can inhibit leukocyte emigration and adherence. Finally, 1 study found that a course of metronidazole resulted in a marked decrease in the amount of inflammatory infiltrate in cap polyps and the subsequent resolution of this condition.2

If the disease persists or recurs despite medical management, surgical resection of the affected colon and rectum is generally indicated. The optimal time for surgery is unknown. However, every patient should be given a trial of medical management before proceeding to surgery. A repeat colonoscopy should be performed prior to surgery to confirm the presence and extent of disease. Cap polyposis has been reported to progress proximally; thus, colonoscopy helps to plan the extent of the required resection. Intraoperatively, examination of the resected specimen is necessary to ensure that the entire diseased colon is resected with adequate margins. Recurrence after surgery is not uncommon and can be the result of inadequate surgery or abnormal colonic motility affecting the entire colon. When recurrence occurs after surgery, repeat surgery is recommended.

楼主您的图片感觉比我找到的很多图片都经典!

除了这张:

Diagnosis:

Inflammatory "cap" polyp (炎症性帽状息肉)![]()

Discussion

Cap polyposis is an uncommon disease first described by Williams et al in 1985 and was proposed to represent a response to chronic mucosal prolapse . Since that time, fewer than 50 cases have been reported in the literature. Cap polyposis probably affects men and women with near equal frequency and variations in gender distributions among different studies likely reflect the small number of patients evaluated to date. This disorder may occur within any racial group, but is more commonly reported in eastern and southeastern Asia. It also occurs within a wide age range, affecting patients as young as 12 years of age, as well as older adults. At least 50% of patients do not have a history of chronic constipation or straining prior to the onset of cap polyposis. In one recent review of 11 patients, the male/female ratio was 9/2, with a mean age of 20 years (range: 15-54 years); 64% of patients had a history of chronic constipation. In that study, only two patients had documented abnormal anorectal function, including one with rectal intussusception and one with rectal prolapse . ![]()

Patients with cap polyposis commonly present with symptoms of mucoid diarrhea, which may be associated with protein wasting, rectal bleeding, or tenesmus. The rectum is involved in more than 80% of cases; however, the disease often affects the sigmoid colon and may even extend into the ascending colon in a retrograde, continuous fashion. Endoscopically, the polyps are usually sessile and vary from a few millimeters to several centimeters. As in the current case, the polyps may form confluent plaques on the mucosal surface. The lesions, which may be solitary or multiple, are often friable and erythematous with ulceration . ![]()

Cap polyps are characterized by several features. Most are composed of elongated, hyperplastic crypts lined by mucin-depleted epithelial cells that show regenerative changes, including nuclear enlargement and increased mitotic activity. The surface epithelium is often attenuated and may be ulcerated. As a result, there is usually an inflammatory "cap" of granulation tissue on the surface with adherent mucin, fibrin, inflammatory cells, and denuded epithelial cells. The lamina propria shows a variable amount of active inflammation, particularly in the superficial areas underlying erosions or ulcers. Although a small number of smooth muscle fibers may emanate from the muscularis mucosae in some cases, most cap polyps do not contain abundant smooth muscle fibers within the lamina propria. ![]()

The differential diagnosis includes a number of unrelated entities that share gross and/or histologic overlap with cap polyposis and encompasses forms of colitis to several polyposis syndromes.

Ulcerative Colitis

Based upon the gross appearance of the colon, ulcerative colitis with pseudopolyps is included in the differential diagnosis of cap polyposis [23]. However, the intervening mucosa is usually endoscopically normal in patients with cap polyposis, whereas patients with ulcerative colitis show erythema or other features of colitis in the non-polypoid mucosa. The histologic features of ulcerative colitis are also distinct from those of cap polyposis. For example, although pseudopolyps in chronic colitis may show features that closely resemble the normal colonic mucosa, or show chronic colitis with or without active disease, cap polyps show predominantly hyperplastic/regenerative changes with cystically dilated crypts or crypts with limited luminal serration, in a background of normal or near-normal lamina propria cellularity with minimal mononuclear cell inflammation, despite the presence of superficial ulceration. In addition, the intervening, non-polypoid mucosa may show mild crypt architectural distortion, but lacks mononuclear cell inflammation in the lamina propria. The presence of active inflammation with ulceration in a background mucosa that lacks chronic inflammation would be distinctly uncommon in patients with new-onset ulcerative colitis. ![]()

Mucosal Prolapse Syndrome

The inflammatory appearance of cap polyps may overlap morphologically with the type of lesions seen in mucosal prolapse or solitary rectal ulcer syndrome leading some investigators to propose that cap polyposis represents one of a spectrum of changes seen in mucosal prolapse [11, 18]. Both conditions show a predilection for the left colon, and, particularly, the rectum. However, the morphologic features of these two entities are sufficiently different to allow their distinction. For example, although cap polyps may be ulcerated with granulation tissue, they do not show other features typical of mucosal prolapse, such as ischemic-type injury or fibromuscularization of the lamina propria. The muscularis mucosae is histologically normal in most cap polyps, whereas it is usually thickened and associated with wisps of smooth muscle that extend into the lamina propria in mucosal prolapse. Cap polyposis has also been reported to involve the proximal colon, including the cecum, which are presumably unaffected by mucosal prolapse, particularly among asymptomatic patients [9, 21]. Although it is likely that cap polyposis and mucosal prolapse are both non-neoplastic, inflammatory processes, it is probable that these entities are unrelated. ![]()

Hamartomatous Polyposis

The polyps of cap polyposis may show morphologic features that raise the possibility of a hamartomatous polyposis syndrome, such as juvenile polyposis, Cowden's syndrome or Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Juvenile polyps show cystically dilated crypts within an inflamed stroma rich in eosinophils, often with surface ulceration and granulation tissue. The cystically dilated crypts of these polyps are evenly distributed throughout the polyp and the lesions may occur in extracolonic sites. In contrast, cystically dilated crypts in cap polyposis are more prominent toward the surface of the polyp, which also contains elongated crypts with luminal serration. Adherent mucin with inflammatory cells is also more commonly seen in cap polyps than in juvenile polyps. Polyps seen in Cowden's syndrome or Cronkhite-Canada syndrome may show features that, in isolation, mimic the features of cap polyposis, but they contain numerous mucus-filled cystically dilated crypts distributed throughout all areas of the polyp, more closely resembling juvenile polyps. Both of these disorders are also associated with extracolonic lesions involving the upper gastrointestinal tract as well as extraintestinal manifestations and dermatologic abnormalities. For instance, Cowden's disease is associated with breast cancer, thyroid disease, facial anomalies, renal cell carcinoma, lymhomas, papillomatosis of the lips and oropharynx, retinal gliomas, and skeletal changes as well as facial tricholemmomas, melanoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma [5, 25]. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome may produce clinical symptoms, such as protein wasting and diarrhea, similar to cap polyposis, but is also associated with skin hyperpigmentation, vitiligo, alopecia, onychodystrophy, glossitis, and cataracts [3, 6]. Knowledge of the clinical scenario usually allows distinction among these entities. ![]()

Cap polyposis may resolve spontaneously; however, most patients require some form of medical or surgical management [12, 16, 24]. Those with fewer than 10 polyps may be managed successfully with polypectomy alone in approximately 60% of cases. More extensive, symptomatic disease may be treated with a combination of stool softeners, anti-inflammatory agents (5-aminosalicylic acid, sulfasalazine, prednisolone) or antibiotics (metronidazole). Recently, some authors have reported endoscopic and histologic resolution of disease following infliximab therapy, suggesting a role for inflammatory mediators, such as TNF- a, in the progression of this disease [2, 13]. Rare patients with concomitant H. pylori gastritis have also been successfully managed with H. pylori eradication therapy [1, 15, 17]. Resection of the involved colon is usually reserved for patients who fail medical therapy. Recurrent symptomatic disease has been reported in up to 37% of cases following limited resection of the affected colon [22]. ![]()

The pathogenesis of cap polyposis is unknown. Its usual involvement of the rectum and/or sigmoid colon, clinical association with constipation and straining upon defecation, and histologic features have led investigators to suggest that these polyps are related to mucosal prolapse or intraluminal trauma [4, 8, 12, 18]. Most investigators believe that it represents a non-neoplastic inflammatory response to mucosal prolapse and consider it to be part of a spectrum of changes in mucosal prolapse syndrome. However, most patients with cap polyposis do not have a history of chronic constipation; larger series indicate that this disease usually occurs in patients in whom mucosal prolapse is infrequent, such as younger male patients without underlying colonic motility disorders [14]. Some reports have also described cap polyposis in association with diverticular disease, colorectal carcinoma, and colitis, suggesting that it may be a non-specific mucosal response to another underlying disorder [22, 26]. ![]()

The most intriguing hypotheses regarding the pathogenesis of cap polyposis implicate an infectious organism in the development of this disorder. Shimizu et al reported a case of cap polyposis in association with an E. coli colonic infection [22]. Although broad-spectrum antibiotics have proven ineffective in the treatment of most patients with cap polyposis, metronidazole is temporarily effective in ameliorating symptoms in some cases [8]. Several investigators have independently reported the successful resolution of cap polyposis in patients receiving H. pylori eradication therapy. Five such cases have been reported to date, all in patients who failed other forms of medical (steroids, metronidazole, bowel rest) or surgical therapy. In each case, the patient was found to have H. pylori-associated gastritis during the course of the illness, which was treated. All of the patients experienced a resolution of colonic symptoms after successful H. pylori eradication [1, 15, 17]. Based on these observations, the authors concluded that cap polyposis may represent an inflammatory response to an unidentified agent that shares an antibiotic sensitivity with H. pylori.

Discussion

Cap polyposis is a rare intestinal condition that was first described by Williams and associates in 1985 in a case series of 15 patients.1 These patients had distinctive inflammatory polyps without a significant family history or strong associations with other major colorectal diseases. From 1985 to 2004, 17 additional cases of cap polyposis were reported in the English language medical literature. Because of the rarity of this condition, these polyps are sometimes misdiagnosed as pseudopolyps in ulcerative colitis.2 In 2004, the second largest case series to date was published by Ng and colleagues, which included 11 cases of cap polyposis reported from 1993 to 2002.2 Our case study is the ninth reported case in the English language medical literature since 2003.

A review of the literature shows that cap polyposis tends to affect individuals of any age, at a median age of 52 years (range, 12–76 years).2 This finding is consistent with the average age of patients with cap polyposis reported over the past 7 years (52.8 years; range, 33–76 years).3–8 A case series conducted by Ng and coworkers showed that males are primarily affected by this condition; however, previous studies have found that females are affected more often than males (11%).2–8

Common symptoms of cap polyposis are mucous diarrhea, tenesmus, and rectal bleeding.9 Mucous diarrhea in these patients can be severe, resulting in excessive protein loss.2 A direct loss of protein from cap polyposis was confirmed in a 54-year-old woman via scintigraphy of technetium 99m-labeled diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid complexed to human serum albumin.10 There have also been reports of lower limb edema as a result of protein-losing enteropathy from cap polyposis. Likewise, approximately half of patients experience habitual straining during defecation and have chronic constipation.2

Endoscopically, cap polyps are small, red, sessile or semipedunculated, and range in size from several millimeters to 2 cm. The number of polyps varies from 1 to more than 100, and polyps are usually located at the apices of the mucosal folds, with normal intervening mucosa. The rectum and rectosigmoid colon are the most commonly affected sites, whereas the entire colon and stomach are rarely affected.2,10 Cap polyps are often covered with a thick layer of fibrinopurulent exudates. Performing a complete colonoscopy is important because cap polyposis has been reported to extend as far as the cecum. Polypectomy should be attempted for all polyps; however, it may not be possible to attain this goal if there are numerous polyps. In this scenario, adequate biopsies should be taken for histologic examination.2

Histologically, these polyps consist of elongated, distended, tortuous, and hyperplastic crypts that become attenuated toward the mucosal surface. The surfaces of these sessile polyps are ulcerated and covered by a thick layer of fibrinopurulent exudates, hence the term “cap polyps.” The lamina propria of the polyps also contains a large number of inflammatory cells.2

Morphologically, polyps associated with cap polyposis are distinct. Patients with cap polyposis are often misdiagnosed with ulcerative colitis or another inflammatory bowel disease (in 44.4% of cases over the past 8 years). Although inflammatory pseudopolyps in inflammatory bowel disease can have granulation tissue, the intervening mucosa has changes classically associated with inflammatory bowel disease. In contrast, the intervening mucosa is normal in cap polyposis. Due to the large numbers of polyps in these patients, a diagnosis of familial adenoma-tous polyposis is often considered; however, histologi-cally, the polyps in cap polyposis are not adenomatous. Finally, due to the variable presence of protein-losing enteropathy, Cronkhite-Canada syndrome can also be considered; however, the polyps in cap polyposis are not hamartomatous.

The exact etiology of inflammatory polyps in cap polyposis is still unknown.2 Buisine and associates found that the mucus in cap polyposis differs from that of the normal colon in terms of ultrastructural characteristics and com-position.11 However, the exact cause of protein loss has not been reported. In an attempt to investigate the presence of lymphatic channels in these polyps—which could lead to protein loss—a D2-40 stain was performed in this case, yielding negative results. Immunohistochemical stains proved the presence of vessels in the cap.

The exact cause of polyps with fibrinopurulent caps is also unknown; however, many researchers attribute these polyps to abnormal colonic motility and repeated trauma to the colonic mucosa caused by straining during defecation. Similar histologic features are present in conditions such as prolapsing mucosa, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, inflammatory cloacogenic polyps, and gastric antral vascular ectasia. Along with cap polyposis, these conditions comprise “mucosal prolapse syndrome” and are all caused by chronic straining at stool.2 In our case report, Figure 8 demonstrates the obliteration of the lamina propria by smooth muscle fibers.

The clinical course of cap polyposis has not yet been elucidated. This condition may, at times, have a self-limiting course, whether or not polypectomy is performed. However, complete polypectomy should be performed whenever possible, as it may be curative in some patients.2–6 Patients are advised to avoid straining during defecation if they have a history of difficult defecation or chronic constipation. Various medical treatments have been advocated, including metronidazole, immunosuppressive agents, and Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy.2 Numerous studies throughout the years have shown complete resolution of cap polyposis following therapy for H. pylori infection. Over the past 8 years, 4 of 9 (44.4%) cases were effectively treated with antibiotics commonly used for H. pylori infection.5,8 The role of met ronidazole in treating cap polyposis may be related to its anti-inflammatory effect rather than its antibiotic action; by acting as a radical scavenger, it can inhibit leukocyte emigration and adherence. Finally, 1 study found that a course of metronidazole resulted in a marked decrease in the amount of inflammatory infiltrate in cap polyps and the subsequent resolution of this condition.2

If the disease persists or recurs despite medical management, surgical resection of the affected colon and rectum is generally indicated. The optimal time for surgery is unknown. However, every patient should be given a trial of medical management before proceeding to surgery. A repeat colonoscopy should be performed prior to surgery to confirm the presence and extent of disease. Cap polyposis has been reported to progress proximally; thus, colonoscopy helps to plan the extent of the required resection. Intraoperatively, examination of the resected specimen is necessary to ensure that the entire diseased colon is resected with adequate margins. Recurrence after surgery is not uncommon and can be the result of inadequate surgery or abnormal colonic motility affecting the entire colon. When recurrence occurs after surgery, repeat surgery is recommended.

高人啊

- MQ